Boz del puevlo, boz del sielo.

The voice of the people is

the voice of the heavens.

—Judeo-Spanish proverb

“Salonica is neither Greek, nor Bulgarian, nor Turkish; she is Jewish,” proclaimed David Florentin, a journalist and the vice president of the Maccabi club of Salonica, amidst the Balkan Wars (1912–1913). After more than four hundred years under Ottoman rule, Salonica (Thessaloniki in Greek)—a strategic Aegean port city at the crossroads of Europe and the Middle East and the gateway to the Balkans—now faced the possibility of being annexed to Greece or Bulgaria. Their armies occupied this “coveted city,” and their representatives courted the “Jewish citizens of Salonica,” whom they perceived to be influential and whose support they wanted.1 But Florentin feared that constricting the city to the borders of Bulgaria or Greece would cut ties with markets in the Balkans and devastate the city’s economic raison d’être, the port, from which the merchant classes—and much of the urban population as a whole—derived their livelihoods: “Salonica would become a heart that would cease to beat, a head that would be severed from its dismembered body.” In petitions to the World Zionist Organization in Berlin, Florentin boldly argued that, if preservation of Ottoman rule could not be assured, Salonica should be transformed into a international city, like Tangiers or Dalian (in Manchuria), guaranteed by the Great Powers and policed by the Swiss or the Belgians but preferably with a Jewish administration—a kind of autonomous Jewish city-state.2

Florentin argued that such a seemingly unexpected scenario was the only reasonable fate for Salonica, the “Queen of ‘Jewishness’ in the Orient.” Salonica represented a dynamic Jewish center, where the majority of the population was Jewish—and purportedly had been so since the arrival of Sephardic Jews expelled from Spain in 1492. Jews could be found in all strata of society as bankers, businessmen, retailers, merchants, civil servants, boatmen, and port workers. In laying out his argument, Florentin echoed grand characterizations of his city by visitors to this “Pearl of the Aegean.” Right-wing Zionist leader Vladimir Jabotinsky, who visited in 1909, referred to Salonica as “the most Jewish city in the world,” the “Jerusalem of Turkey,” where even the post office closed on the Jewish Sabbath. Labor Zionist David Ben-Gurion, who sojourned in the city in 1911, remarked that Salonica constituted “a Jewish labor city, the only one in the world.” British and French travelers further emphasized the “predominance” of the “chosen people” in this “New Jerusalem,” where the Jewish Sabbath was “most vigorously observed,” and where, they speculated, the Temple of Solomon might be rebuilt or the messiah would appear.3

Amidst a cauldron of competing claims over the future of Salonica made by the Great Powers, international organizations, and major newspapers, the city emerged as the “cockpit of the Eastern Question,” the site where, according to political commentators, the fate of all Ottoman territories would be determined.4 The Austro-Hungarian Empire viewed the city as the “gate to the Mediterranean” and saw the benefits of establishing an independent Jewish statelet that would guarantee the empire’s access to a warm water port.5 The Jewish Territorialist Organization, which advocated for the creation of a Jewish homeland anywhere in the world, similarly supported the plan. The New York Times suggested that the creation of an autonomous Jewish Salonica appeared more feasible than a future independent Jewish state in Palestine, for the latter would have to be built virtually from scratch.6 The Alliance Israélite Universelle in Paris and the Anglo-Jewish Association in London also expressed support. In contrast, the World Zionist Organization met the proposition with ambivalence on the grounds that the creation of a Jewish state in Salonica would undermine the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. The main Judeo-Spanish newspaper of Istanbul, El Tiempo, dismissed the prospect of Jewish autonomy in Salonica as a “fantastical” and “utopian” scheme.7

Most strikingly, Salonican non-Jews expressed preference for Jewish rule or internationalization. Local Muslims, Vlachs, Jews, and Dönme (descendants of Jewish converts to Islam who were officially recognized as Muslims) formed the Macedonian Committee to advocate for internationalization, arguing that the “principle of nationalities,” which underpinned the concept of “self-determination” championed by US President Woodrow Wilson, should be applied to Salonica like everywhere else—and thus Jews, who formed the predominant “national” demographic element in the city, ought to reign sovereign.8 A similar constituency of merchants at the city’s Chamber of Commerce further contemplated transforming Salonica into a free city and encircling it with barbed wire to minimize smuggling.9 But none of these proposals was to be. Greece permanently annexed the city in 1913.

The dream of Jewish autonomy, the possibilities of internationalization, and aspirations for a different future for Salonica did not disappear. Following the Balkan Wars, many Salonican Jews dispersed across the globe as “exiled sons” in the wake of the capture of their “motherland,” Salonica, by Greece. Some who settled in New York anticipated the arrival of a “cleansing deluge” with World War I that would transform Salonica into the capital of an autonomous Macedonia—and thus precipitate their return from temporary exile.10 Perhaps Greek statesman Ion Dragoumis’ vision for an “Eastern Federation” would unite all the peoples of the region through shared state governance.11 Or maybe a proposal to the Spanish government by a Salonican Jewish merchant, Alberto Asseo, for the creation of the “United States of Europe” would gain traction.12

Again appealing to the principle of nationalities, a well-known Salonican Jewish journalist, Sam Lévy, then residing in Lausanne, submitted a final plea to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. Only if Salonica were given international recognition and administered by the Jews as a neutral, yet demographically predominant, population (“two-thirds” according to Lévy) would Salonica “enter the great family of the League of Nations,” assure “tranquility in the Balkans,” and “guarantee European peace.” Levy’s fashioning of Salonica’s Jews as the sovereigns of a distinct Salonican “nation,” on a par with other European nations, constituted the most audacious claim about the city’s possible status and a creative resolution to the problems generated by the post-imperial world.13

One wonders what direction Balkan and European geopolitics might have taken if any of the bold visions for Jewish autonomy or internationalization of Salonica had succeeded. The idea of transforming Salonica into a kind of free city if not a Jewish city-state may strike us in the twenty-first century as quaint, if not absurd, but it emerged from realistic expectations at the time, as evidenced by the creation of similar types of polities in the region: Turkish-speaking Muslims in Gumuldjina (Komotini), in Thrace, established an independent albeit short-lived state in 1913.14 Why not something similar in Salonica for Jews? The case presents an intriguing counterfactual for a work of fiction along the lines of Philip Roth’s Operation Shylock or Michael Chabon’s Yiddish Policeman’s Union. It also unsettles our assumptions about the possibilities of Jewish sovereignty in the modern era and the inevitability of the collapse of empire and the triumph of the nation-state.

The alternative proposals for Salonica’s future represent only a fraction of the multiple responses to the transition from Ottoman to Greek rule by different segments of the city’s Jews, who neither acted as a unit nor resigned themselves to the fortune imposed upon them. Jewish Socialists advocated that the city be incorporated into Greece or Bulgaria or benefit from an international regime—any option other than remaining under Ottoman rule—in order to gain greater “liberty.” When it became clear that the city would become part of Greece, Jewish Socialists promptly initiated Greek language courses for their constituents.15 In reaction to the Greek army’s entry into the city in October 1912, a prominent Jewish educator, Joseph Nehama, insisted that the Jewish masses “maintained a most dignified and proper attitude. Certainly they have shown no hostility, but neither have they shown satisfaction. . . . What will be the new conditions created for our fellow Jews . . . ?”16 While initially sharing the ambivalence of the Jewish masses as identified by Nehama, Chief Rabbi Jacob Meir soon welcomed King George I of Greece to Salonica, affirmed his loyalty to the Greek crown on behalf of the Jewish population, and bestowed a blessing upon the king.17 But when King George I of Greece was assassinated near the White Tower in 1913, Greek newspapers falsely accused the Jews until it became clear that the assassin was a Greek anarchist; even then, tensions between the two populations did not subside.18

The transfer of Salonica to Greece in 1912 became a turning point during more than a decade of war (1911–1923) that facilitated the end of the Ottoman Empire and resulted in mass carnage. Over two million residents of Asia Minor lost their lives, including nearly a million victims of the Armenian genocide. Millions of refugees fled across crumbling imperial borders and newly drawn national boundaries; others traversed seas and oceans both voluntarily and forcibly in what became one of the largest population movements in human history.19 In the wake of World War I (1914–1918), the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922)—which Greece remembers as the “Great Catastrophe” and Turkey designated as the “Turkish War of Independence”—resulted in the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), which formalized a compulsory population exchange between the two countries on the basis of religious affiliation: with some exceptions, a half million Muslims were expelled from Greece and sent to Turkey, whereas one and a half million Orthodox Christians were expelled from Turkey and resettled in Greece. The same religious categories that had underpinned the Ottoman imperial social order were recast anew as the primary markers of national belonging. In the case of Salonica, Muslims (and Dönme) departed, and a hundred thousand Orthodox Christians arrived. Exempted from the population transfers, Jews largely remained in situ. Rather than transporting themselves to a different country, a different country had come to them. From a demographic plurality (or majority, depending on the statistics cited) in Ottoman Salonica, Jews ceased to serve as the sovereigns of the city and instead became a minority confronting unprecedented pressures from the new state and from their neighbors.

During this period of transition, Salonica’s Jews developed a repertoire of strategies to negotiate their position and reestablish their moorings in the changing political, cultural, and economic landscape. Jewish Salonica tells the stories of a cross-section of Salonica’s Jews and situates them as protagonists engaged in an ongoing process of self-fashioning and adaptation amidst the tumultuous passage from the multireligious, multicultural, multinational Ottoman Empire to the homogenizing Greek nation-state. While keeping in mind the devastation wrought by the Holocaust, which decimated Salonica’s Jewish population, this book highlights how Jewish actors of varying classes, professions, and political affiliations, speaking as individuals or on behalf of institutions, as official or unofficial representatives of the Jewish collectivity, sought to shape their destiny and secure a place for themselves in the city, the province of Macedonia, the Ottoman Empire and subsequently the Greek state, and the broader Jewish world.

Instead of emphasizing the rupture between the Ottoman and modern Greek worlds that seemed to provoke an inexorable period of decline for Salonica’s Jews leading up to World War II, this book also explores the legacies of the cultural, legal, and political practices of the late Ottoman Empire on the consolidating Greek state that reveal the continuing dynamism of Salonican Jewish society. As a tool to govern its diverse populations and maintain order, the Ottoman state recognized its non-Muslim populations (namely Jews and Christians) as distinct, largely self-governing communities (millets) protected by imperial privileges. Vestiges of this form of millet governance, which imbued religious communities with a modicum of “non-territorial autonomy” within the borders of the state, outlived the empire itself especially as evidenced in the legal and political structures of post-Ottoman states such as Egypt, Lebanon, Israel, and Turkey.20 Greece should also be included in this list, for it, too, inherited and adapted some of the tools of Ottoman state governance to manage its own diverse populations. As the Ottoman state did for non-Muslims, Greece recognized its non-Christian populations (namely, Jews and Muslims) as distinct religious communities endowed with certain powers of self-government—this time in the name of minority rights.

Jewish Salonica recognizes both the continuities and ruptures between the Ottoman Empire and modern Greece while shifting attention away from the state and toward the people. The book highlights how Salonica’s Jews emphasized their sense of local identity during the passage from empire to nation-state and at the crossroads of Ottomanism and Hellenism. During this period of readjustment, Salonica’s Jews re-anchored themselves in the city and embraced the city itself—and no greater territory—as a kind of homeland. Salonican Jewish leaders believed that reaffirming their connection to the city and their status as Salonicans would bridge the gulf that separated the world of the receding Ottoman Empire from that of the ascendant Greek nation-state. They localized their sense of citizenship by relying on their rootedness in Salonica to justify their participation in the Ottoman and subsequently Greek polities. The more the demographic predominance of Jews in Salonica diminished under Greek rule, the more Jewish leaders reinvested in their sense of connection to the city, reinventing it either as a distinctly Jewish site and symbol or as an unquestionably Greek topos to which Jews nonetheless belonged. Visions of “Jewish Salonica” (Saloniko la djudia), as Judeo-Spanish sources referred to the city, served as surrogates for the dream of Jewish autonomy, as substitutes for lost imperial allegiances, and as inspiration for Jews to reroot themselves in the aftermath of empire, within the context of the new Greek nation-state, and on the new map of twentieth-century Europe. City-based identity in the case of Salonica constituted a legitimate and modern mode of self and collective expression that competed with other categories of belonging, such as nation, religion, class, or ideology, sometimes complementing these latter affiliations, at other times challenging them.

Jewish activists transformed Salonica into a stage for the articulation of a variety of political positions and developed visions of the city in service of their agendas. Salonica’s Jewish socialists viewed the city as home to “the most important Jewish community in the Balkans” not only for all of its accomplishments, but also because they still hoped that the Jewish working class would one day triumph in the city as in Jewish institutions.21 They construed their local activism as rehearsal for a larger class revolution. Zionists also saw the city, after World War I, as a staging ground for a future independent Jewish state. From their perspective, Tel Aviv, the new Hebrew city, was to become a New Salonica, just as Salonica, the “Hebrew City in Exile” par excellence, had become a New Jerusalem. They argued that the city’s Jews, once de facto rulers of Salonica, ought to play a central role in building a Jewish state in Palestine.22 In contrast, Liberals who advocated for integration construed Salonica as the “Macedonian Metropolis” and envisioned the cooperation of Jews and Orthodox Christians within a modern framework of “Hellenic Judaism” as key to the city’s prosperity and as a model for intercommunal relations moving forward. From each perspective, the city—as space, idea, and identity—remained central.

The case of Salonica also offers a window into the anxieties and aspirations of an urban Jewish population grappling with the unprecedented challenges that confronted Jews across Europe during the early twentieth century in the context of war and the redrawing of the map. Salonica occupied a central position in the Sephardic orbit in the Balkans and the eastern Mediterranean, with cultural, commercial, political, and familial links to Istanbul and Izmir, Sarajevo and Sofia, Monastir and Rhodes, Jerusalem and Cairo. A Sephardic studies scholar from Turkey, Maír José Benardete even touted Salonica as an “archetype of a Levantine Sephardic community,” after which all other Jewish communities in the region patterned themselves.23 After its incorporation into Greece and the breakdown of the Judeo-Spanish cultural sphere, Salonica played a key role for the country’s Jews. The Jewish Community of Salonica imported several tons of flour each year to manufacture matza for Passover and organized twenty-three communities—from Athens to Corfu—into the Union of the Jewish Communities of Greece to defend the interests of Hellenic Judaism (1929).24 A Jewish notable in the town of Demotika encapsulated the reliance of Greece’s Jews on Salonica: “In small communities in the provinces where we often live in hopeless situations, we have always had as consolation and hope that in a moment of anguish we can count on the saving graces of the great Jewish agglomeration of Salonica.”25

Salonica’s Jews also cultivated links with Jews beyond their immediate geography that brought them into conversation with broader Jewish and general cultural, political, and social trends that profoundly impacted local dynamics, whether through the Alliance Israélite Universelle in Paris, the Board of Deputies of British Jews in London, the World Zionist Organization in Berlin, or informal connections fostered by Salonican Jewish intellectuals who read and published in Jewish journals in Poland. Unlike the Ashkenazic context, divisions between Reform and Orthodox Judaism never impacted Salonica (nor any of the other former Ottoman locales). Like the Ashkenazic context, however, a wide range of Jewish political movements did develop in Salonica, from various versions of Zionism to Jewish socialism and communism whose organizers created more than ten specifically Jewish political parties during the interwar years—a fraught dynamic that looked more like Warsaw than Istanbul. Across the continent, in Vilna and Bialystok, Prague and Vienna, Sarajevo and Istanbul—as in Salonica—Jews proposed their own solutions to the changing political landscape, grappled with new meanings of “nation” and “state,” and reconceptualized their relationship to their city in the context of shifting boundaries and “unmixing of peoples” that accompanied the collapse of the Habsburg, Romanov, and Ottoman empires.26

They often reimagined their city as an exceptional “earthly Jerusalem” (Yerushalayim shel mata) to which they forged strong attachments without necessarily relinquishing their faith in the “heavenly Jerusalem” (Yerushalayim shel mala).27 Salonican Jews elaborated a set of narratives about their city as a historic Jewish metropolis and a Jewish homeland, a concept ultimately cemented with the designation of the city as the “Jerusalem of the Balkans.” By drawing analogies to Jerusalem, Jewish activists sought to render their city relevant and central to the Jewish experience and, during an era of transition, to legitimize their role as meaningful participants in their city, in their country, and in the broader world. If Salonica’s Jews saw their city, like Jerusalem, as their “mother city,” their ir va-em be-Israel (literally, “city and mother in Israel,” 2 Samuel 20:19), they were not alone, for the city was also known in Greek as the “mother of refugees” and the “mother of Orthodoxy.”28 All agreed that Salonica was a mother city—but whose mother was she?

Confronting Salonica’s Ghosts

The dynamic engagement of Salonica’s Jews in the politics, culture, and economics of the city in addition to their devastating destruction during the Holocaust were, for a long time, expunged from the city’s history and public memory as part of a nationalizing process that sought to render Salonica exclusively and perpetually “Greek.” Such liminal status led one scholar to characterize Jewish Salonica—excised not only from the Greek national narrative but also marginalized in Europe-centered modern Jewish studies—as an “orphan of history.”29 The end of the Cold War and the possibilities of considering “the other” in society in a new light finally spurred greater interest in Jews in Salonica and Greece. The post-Cold War era of the 1990s became the “coming out” phase of Jewish history in Greece. The naming of Salonica as the Cultural Capital of Europe in 1997 introduced discussion of the Jewish presence in the city in a public forum for the first time, and the conversation continues to be informed by a celebratory interest in and nostalgia for the so-called cosmopolitan and multicultural world of Ottoman Salonica. Increased interest—not only in Greece but also among scholars in France, Israel, and the United States—initiated a “post-celebratory,” critical phase in the study of Jewish history in Greece, to which this book seeks to contribute.30

At the intersection of the coming out and post-celebratory phases, Mark Mazower’s Salonica, City of Ghosts (2004) offered the first accessible overview in English of the history of Salonica from the Ottoman conquest in 1430 until the end of the World War II. Mazower presented the “cultural and religious co-existence” of the city’s multiple residents within “a single encompassing historical narrative” that would not privilege the Jewish, Muslim, or Christian perspectives. Mazower indicated that he found a model for such an inclusive narrative that emphasized the “hybrid spirit” of Salonica in a work composed by a “local historian” in the wake of the Balkan Wars.31 This local historian was none other than the Jewish educator and banker, Joseph Nehama, who penned La Ville Convoitée under the pseudonym P. Risal in 1914.

It is important to note that the author of such an inclusive history was Jewish precisely because, in the wake of the Balkan Wars, only a Jew—unconnected to irredentist nationalisms and not speaking on behalf of any state in the region—could dare to write an inclusive history of such a coveted city. He could do so precisely because he spoke from the margins of political power while drawing upon a sense of confidence and legitimacy derived from his position as a representative of the local voice. Such an endeavor was dangerous and could sow the seeds of nationalist animosity—hence Nehama’s decision to publish the book using a discrete pen name. Although not culturally, demographically, or economically marginal in Salonica at the time, Jews lacked political power, did not have an army behind them, and could more readily imagine a story from the margins, one that decentered the state and acknowledged the range of residents inhabiting the city. Jewish Salonica seeks to recover the local milieu that produced figures like Nehama, who saw themselves not only as Jews but also as spokesmen for their city, sometimes inclusive of all of its diverse inhabitants, while other times prioritizing Jewish perspectives. Even Nehama moved between both positions: while emphasizing the role that a multiplicity of populations played in the city’s history, he drew a clear conclusion about the identity of Salonica: “today it is Jewish and Spanish: it is Sephardic.”32

Jewish Salonica contributes to the growing post-celebratory scholarship on the city by focusing on the variegated Jewish experiences in and visions of Salonica. While it involves a discussion not only of Jews but also of their interactions with their neighbors and with the state, it does not offer an all-inclusive narrative. Instead, Jewish Salonica enters the city’s history through a Jewish prism and seeks to reinterpret that history from the vantage point of Salonica’s Jewish residents. One of the book’s primary goals is to temper the general thrust of existing studies that highlight the downward spiral of Salonica’s Jews following the city’s incorporation into Greece. According to these interpretations, after Salonica comes under Greek rule, Jews—like Muslims—are considered “doomed.” The failed plans for internationalization and Jewish autonomy amidst the Balkan Wars emerge, if mentioned at all, as the last hurrah, a final stand of a Jewish population whose incorporation into the Greek nation-state signifies the beginning of the end.33 Jews in Greek Salonica, especially during the tenures of Eleftherius Venizelos as prime minister, are characterized as “the most intractable and alien element” in Greece, “unwanted compatriots,” and “under siege.”34 As these narratives unfold, Jews experience an inexorable period of decline as the objects of nationalizing, anti-Jewish policies and popular actions.35

According to these accounts, very few opportunities emerged for Greek-Jewish rapprochement during the interwar years, and the categories of “Greek” and “Jew” remained fixed along ethnic lines, the former identified as the true nation, and the latter largely considered alien. Only during the dictatorship of Ioannis Metaxas (1936–1941), so these studies suggest, did Salonica’s Jews experience a short respite from the animosity directed against them by their neighbors and by the state prior to World War II. These narratives end with the decisive trauma of Nazi occupation and genocide. In 1943, the Nazis rounded up and deported more than forty-five thousand of Salonica’s Jews—nearly 20 percent of the city’s residents—to their deaths at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Nazis unwittingly solidified the Hellenization of the city by transforming multiethnic Ottoman and Jewish Salonica into a “city of ghosts.” The story most often told of Salonica’s Jews thus ends in destruction, erasure, and the suppression of memory. In these tales, which reinforce a lachrymose conception of Jewish history, Jews in Salonica become objects of nationalist ambition and victims of Greek antisemites or Nazis and their collaborators rather than historical actors in their own right.

These narratives of decline echo interpretations offered by Salonica’s Jewish intellectuals writing in the immediate wake of the war who viewed the period prior to World War II as a prelude to the destruction of the city’s Jews. Still mourning the agonizing annihilation of the city’s Jews during the German occupation, the rabbi and historian Michael Molho in 1948 solidified the perception of the three decades prior to World War II as a period of decline that culminated with the Holocaust: “[T]he Balkan Wars and the First World War gradually decrease the importance of this Sephardic center [Salonica] that declines and is annihilated at the hands of the Nazis, in the terrible year 1943.”36 In search of a more dynamic and complex understanding of the pre-World War II period that avoids a teleological approach, Jewish Salonica disentangles the interwar years from the period of the German occupation and does not interpret them as a staging ground for the Nazi genocide, thereby allowing the story prior to the war to be understood on its own terms.

Some of the available scholarship attributes the decline of Salonica’s Jews to their purported resistance to Hellenization measures that prevented them from really becoming Greek prior to World War II; such an explanation must be reconsidered. Without taking into account the alternative perspectives that permeate this book, recent studies argue that Salonica’s Jews established a “nascent but inchoate” Greek Jewish identity through the 1930s and only came to identify themselves and be identified by others as fully Greek once they left—either in Auschwitz, Israel, or New York.37 Some scholars have even suggested a causal link between Salonican Jews’ alleged failure to become Greek—assuming their own obstinacy was the barrier—and their eradication during World War II. If only Jews in Salonica had learned the Greek language better and assimilated more completely, the argument goes, they could have hidden more easily and more of their Orthodox Christian neighbors would have come to their aid during the German occupation.38

When scholars and commentators argue that Jews in Salonica never really became Greek prior to World War II, they presuppose that the parameters of Greek national and political identity had already been fixed by the interwar years. Jewish Salonica joins a small but growing body of scholarship that argues that the boundaries of national belonging in Greece and the meanings of citizenship were by no means set but rather in the making throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. Like other national identities in the region, Greek national identity had to be learned, coerced, courted, and chosen. As evidenced by the opposition mounted by the Orthodox Christian Patriarchate in Istanbul to the Greek War of Independence in the 1820s and the refusal of peasants near Salonica in the early twentieth century to identify with any nation at all, instead insisting on their status as Christians alone, Greek national identity continued to develop over a long period.39

The ensuing state-led project to Hellenize Salonica after 1912 must be conceptualized as part of this protracted process that involved not only force but also dialogue and compromise between the state and the city’s Jews as well as a variety of other populations in the wider region: Slavic-speaking Orthodox Christians, Orthodox Christian refugees from Asia Minor and the Black Sea region—many of whom spoke Turkish as their primary language (the Karamanlis) or the distinctive Pontic dialect of Greek—as well as a variety of other culturally diverse populations, including Vlachs, Roma, and Slavic-, Albanian-, and Turkish-speaking Muslims in Thrace and Epirus.40 Among these varied populations, only Orthodox Christians, who had constituted the Rum millet in the Ottoman Empire, became the standard bearers of the consolidating Greek nation.41 Salonica’s Jews played an active role in the process, not only as the objects of Hellenizing measures imposed by the state but also as agents who shaped the contours of the enterprise. They argued that even if they could never become full-fledged members of the Greek nation—unless, perhaps, they ceased being Jews—they nonetheless could become Greek patriots, legitimate “Hellenic citizens” (sivdadinos elenos) with shared civic commitments.

A new and expanded source base makes it possible to hear an additional range of voices from Salonica’s Jews that reveal the active role they played during an era of rupture and transition. Until now, the tale of Salonica’s Jews has been told largely from the outside looking in: state records privilege the top-down perspective and prerogatives of bureaucrats and policy makers; travelers’ accounts and consular reports highlight the gaze of the foreigner; and correspondence with international organizations, such as the Alliance Israélite Universelle, reveals observations of a select Jewish elite writing for a European audience. While integrating these invaluable viewpoints, Jewish Salonica offers an unprecedented insider’s view by reference to the hereto-fore largely unstudied official archives of the Jewish Community of Salonica and the extensive outpouring of the local periodical press. These primary sources reveal Salonican Jews’ perspectives regarding their own experiences, articulated principally in the Jewish vernacular and intended for a local Jewish readership. These sources help us understand how Salonican Jews—primarily but not exclusively the elites—explained their world to themselves. They offer additional narratives to the standard one of decline by revealing the previously unrecognized extent to which Jews and their institutions, as well as the Jewish press, not only struggled but also flourished during the interwar years.

Written mostly in Judeo-Spanish but also in Greek, Hebrew, and French, the surviving archives of the Jewish Community of Salonica date from 1917 to 1941 and record the actions of the Jewish Community, its administrators, and its members. Confiscated by the Nazis during the German occupation, they miraculously survived over the past seventy-five years, largely inaccessible, uncatalogued, and dispersed across the globe: in New York (YIVO Institute for Jewish Research), Moscow (the former Osobyi Secret Military Archive), Jerusalem (Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People), and Salonica, where I literally dug materials out of a storage room and transferred them to the city’s Jewish museum.42 While several scholars in Israel have begun to explore some of these archives, Jewish Salonica is the first study to draw on all four repositories.

The communal archives illuminate the interactions of the city’s Jewish institutional body with everyday Jews. While the perspectives of the Jewish literate, male, middle, and leadership classes—journalists, rabbis, teachers, politicians, merchants, and communal functionaries—predominate, Jewish Salonica’s reference to the archives also provides glimpses into the worlds of stevedores, soldiers, prisoners, converts, women, and the impoverished masses who, if illiterate, sometimes commissioned scribes to compose petitions on their behalf or offered oral testimony recorded by the rabbinical court. The archives also document the relations between the Jewish Community and local, regional, and state governmental bodies and with organizations and individuals across the globe. The archives detail the structure and extensive governance of the Jewish Community—its Communal Council, General Assembly, chief rabbinate, school network, Jewish neighborhood administrations, and twenty Jewish philanthropic institutions, including a hospital, a medical dispensary, a soup kitchen, an old age home, orphanages for girls and boys, and an insane asylum. In short, more Jewish institutions operated in Salonica during the interwar years than ever before.

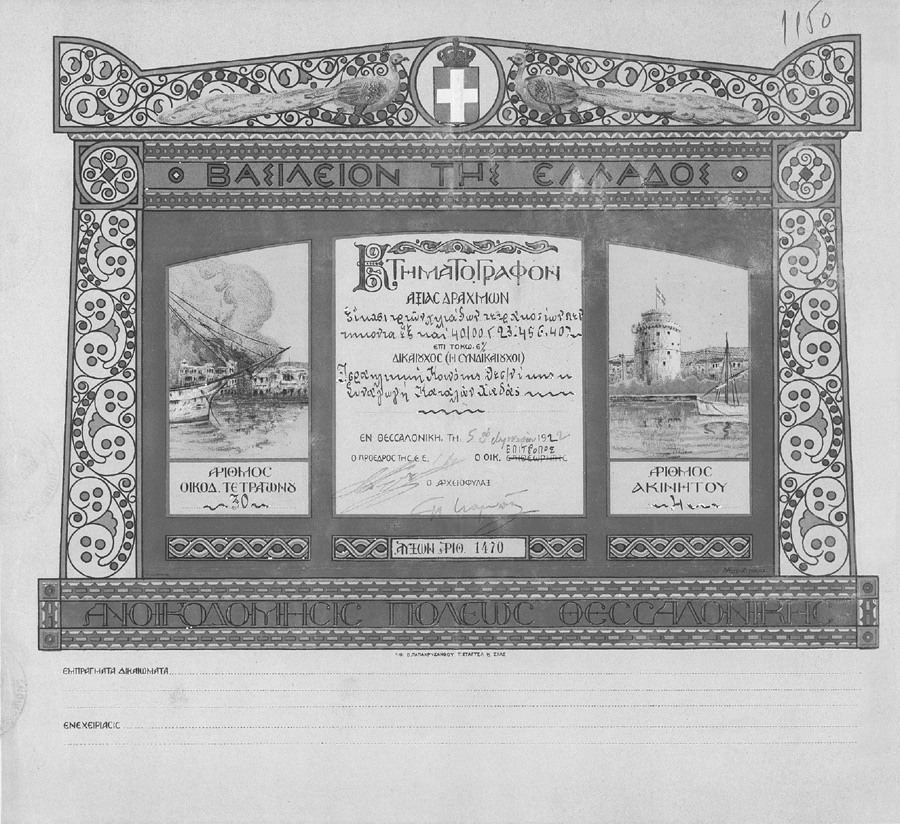

The archives reveal that the Jewish Community of Salonica retained considerable power during the interwar years. Recognized by the Greek state as “a legal entity of public law” (according to Law 2456 of 1920), the Jewish Community functioned in parallel to and in some cases in competition with the municipality of Salonica. The Jewish Community managed its own Office of Statistics and Civil Status modeled explicitly on the Lixiarhio, or the civil registry office, of the municipality. But the Jewish Community benefitted from one additional power not available to the municipality: the right to issue certificates of identity to its members for both domestic and international use.43 The very structure of the Jewish Community represented in the communal archives permitted—in fact compelled—Salonican Jews to retain connections with the communal body throughout the interwar years. The extensive bureaucratic powers of the Community demonstrate that Ottoman imperial practices continued to mold the experiences of Salonica’s Jews once the city became part of Greece.

The local press constitutes the other major source base to help us comprehend how Salonica’s Jews understood their world, responded to it, and reshaped it. Despite a scholarly consensus that Judeo-Spanish print culture experienced a precipitous decline following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, this was not the case in Salonica, where more newspapers and magazines appeared in Judeo-Spanish than in the other major publishing centers combined (105 in Salonica compared to 45 in Istanbul, 30 in Sofia, and 23 in Izmir).44 In Salonica, the period after 1912 constituted the height of Judeo-Spanish publishing. The circulation of the city’s only Judeo-Spanish newspaper in 1898, La Epoka, reached 750. By 1927, the French consul estimated that more than 25,000 copies of Judeo-Spanish newspapers circulated in the city, with 5,000 each of the daily El Puevlo and the Zionist weekly La Renasensia Djudia.45 A visitor in 1929 counted fourteen Jewish periodicals, including seven dailies, and observed that “the Jewish press in Salonica is exceedingly well-developed.”46 Even if illiteracy continued to plague segments of the population, those without direct access to the written word often learned of the latest headlines from relatives or acquaintances. An older style of communal reading continued after 1912, as evidenced by a photograph in National Geographic (1916) of fourteen Jewish men gathered around a man reading a newspaper aloud in one of Salonica’s public squares, suggesting that more individuals gained access to the discussions in the newspapers than subscription figures would suggest.47 The newspapers nonetheless must be understood as primarily representing the voices of literate elites.

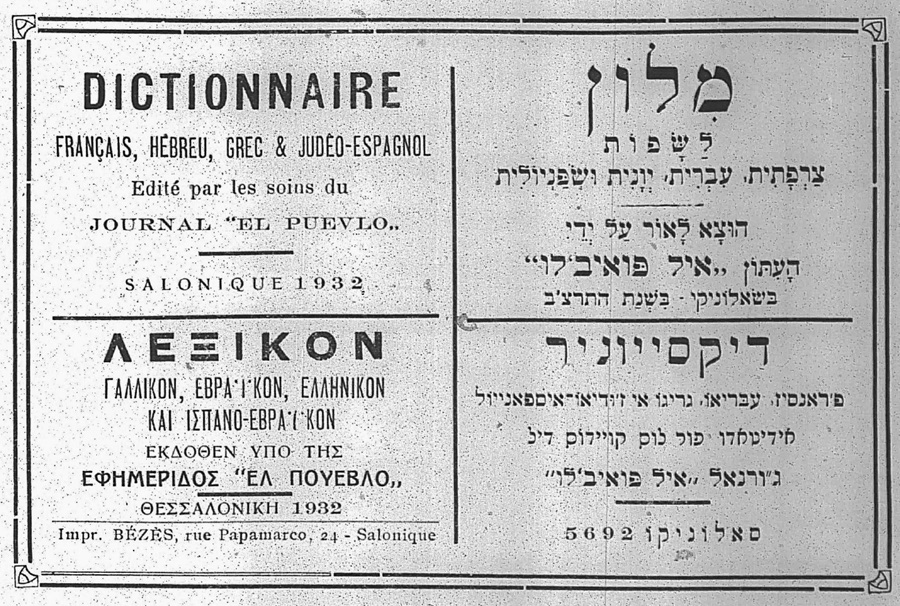

Despite the Hellenizing pressures of the interwar years, the majority of Jewish printed matter in Salonica continued to appear in Judeo-Spanish (in Rashi typeface) until World War II, including the last newspaper, El Mesajero, which the German occupation forces closed down in 1941. But Hellenizing pressures and aspirations also transformed Jewish print culture in interwar Salonica. The mouthpiece of the so-called assimilationists, Evraïkon Vima tis Ellados (Jewish Tribune of Greece), established in 1925, appeared in bilingual Greek and French editions. Rather than obstinately resist the acquisition of the Greek language, Zionists had proposed creating a Jewish daily in Greek even earlier, in 1923.48 The organ of the Zionist Federation of Greece, La Renasenia Djudia (The Jewish Renaissance), introduced a Greek section in 1932 in order to appeal to Jews throughout Greece, a portion of whom knew only Greek; to Jewish youth in Salonica, who increasingly gained fluency in Greek; and to the wider Greek-reading public, to elicit support for the Zionist enterprise.49 Although not assimilationists, Zionists favored accommodating the new realties of life in Greece. Some Jewish newspapers even published multilingual lexicons that highlighted the “four languages of our city”—Judeo-Spanish, Hebrew, Greek, and French—and which local Greek newspapers praised as a “unique work in the world.”50 In interwar Salonica, Greek became a Jewish language—used by Jews—and Judeo-Spanish a Greek one—used in Greece and occasionally by Orthodox Christians: a Greek public notary, for example, printed his business cards in Judeo-Spanish, in Rashi script, to attract a Jewish clientele.51

With reference to the archives and the local press, Jewish Salonica demonstrates how Jews in Salonica harnessed their multiple affiliations—to the city, community, and state, as well as to differing ideological postures and linguistic and cultural expressions—at the intersection of empire and nation-state, as the last generation of the city’s Ottoman Jews sought to transform themselves and their children into the first generation of Salonica’s Hellenic Jews. The sources offer glimpses into the multiple ways in which Salonica’s Jews understood and interpreted the complexities and contradictions imbedded in their experiences. In effect, this book begins to restore the voices of Salonica’s Jews and to tell their stories in their own words.

Salonica’s Jews between City, Community, and State

Jewish Salonica focuses on how Salonica’s Jews sought to secure a place for themselves amidst the transition from the Ottoman Empire to modern Greece in three domains: as Salonicans, as members of the Jewish Community, and as citizens of the state. While Jews—like their Muslim and Christian neighbors—had expressed connections to their city, to their community, and to their state for many generations, the nature and character of those affiliations dramatically transformed beginning in the nineteenth century due to the implementation of centralizing administrative reforms by the Ottoman state, known as the Tanzimat (“reorganization,” 1839–1876). These reforms brought into existence new institutions and new modes of political belonging through the creation of municipalities (in Salonica in 1869); by formalizing the self-governing structures of non-Muslim communities, known as millets (for the Jewish Community of Salonica, in 1870); and by officially transforming the empire’s Muslim, Christian, and Jewish subjects into citizens (introduced in 1856 and formalized by the Ottoman Nationality Law of 1869). Jews in Salonica simultaneously gained three layers of citizenship as they ascertained certain rights and obligations vis-à-vis not only the state but also their community and the municipality. As Jewish Salonica will illustrate, Jews in Salonica continued to renegotiate the relationships between these three affiliations from the late nineteenth century until World War II.

Although the concept of citizenship was new in the nineteenth century, the practice of proclaiming loyalty to the sovereign was not. Jews in the Ottoman Empire had introduced a prayer for the government, Noten teshua lamelakhim (“He who gives salvation to the kings,” Psalm 144:10), into their liturgy in the sixteenth century. The prayer formed part of a long-standing formula in support of the so-called vertical alliance according to which Jews across Europe entrusted their fate to their sovereign.52 The difference is that, while most Jewish communities discarded the Noten teshua in the nineteenth century during the era of emancipation, it continued to be invoked in Salonica until World War II.53 In the context of both the Ottoman Empire and Greece—where the separation of church and state was not introduced—the process of embracing the new responsibilities of citizenship involved the incorporation of religious metaphors. In the wake of World War I, a Jewish notable in Salonica emphasized to his constituency that their future success in Salonica would be contingent upon their embrace of two religions: the religion of Judaism and the religion of patriotism, the latter defined as “the religion of love for the homeland.”54 By invoking allegiances to both religions simultaneously and localizing them in the city, Jewish elite continually sought to fashion themselves and the Jewish masses into local patriots, conscientious Jews, and devoted citizens—ultimately, to transform their “country of residence” (paiz) into their “homeland” (patria).

Beginning in the late nineteenth century, the local Judeo-Spanish press developed a new vocabulary for Salonica’s Jews to describe their evolving relationships with their city, community, and state. The Judeo-Spanish press tethered Jewish residents of Salonica to the city by identifying them as Salonicans: Selaniklis (from Turkish), Salonisianos (from French), and [Te]salonikiotas (from Greek). Salonica’s Jews also described themselves as sivdadinos, as “citizens” of their city, to which they felt a sense of allegiance and where they engaged in political activism (all municipal councils included Jewish members until the 1930s). The status of citizen of Salonica was not reserved for Jews alone; the term konsivdadino (“fellow citizen”) referred to their Muslim and Christian neighbors. In contrast to Orthodox Christian resfuyidos (“refugees”) who arrived from Asia Minor in the 1920s, Jews insisted on referring to themselves until World War II as yerlis (“indigenous,” from Turkish), a further indication of their self-perception as native to the city.

The Judeo-Spanish press also oriented its readers toward the formal institution of the Jewish Community and referred to it simply as “the Community” (la komunita). Throughout the pages that follow, the Jewish Community refers to the formal institution and its official spokesmen, such as the Communal Council or the chief rabbinate. Other times, Judeo-Spanish sources invoked the term komunita to construct an imagined community, a sense of collective belonging among local Jews despite their socially stratified, disunited, heterogeneous composition. Competing individuals or groups, often via the press or voluntary associations and clubs, spoke in the name of the community, often without authorization from the Jewish Community or in opposition to it. The ubiquity of voluntary associations and the defining role they played in shaping public debate led a local newspaper to quip: “Each city has a characteristic that endows it with its particular seal. Paris has its boulevards and bon vivants, Istanbul has its ships and ferries, Naples has its street mobs reaching out to the sun, and Salonica has its clubs.”55 Political, literary, and social clubs along with the local press cultivated broader conceptions of community—focused on the people rather than the institution, on Jewish civil society rather than the governing body—and designated as the “Jewish collectivity” (la kolektivita djudia or la djuderia, literally “Jewry”), the “Jewish population” (populasion djudia), the “Jewish people” (puevlo djidio), the “Jewish element” (elemento djidio), and the “Jewish public” (puvliko djidio). There was considerable slippage among these interrelated concepts and competing visions of what they entailed.

At the level of the state, the Tanzimat sought to win the allegiance of the empire’s residents—inclusive of Muslims, Christians, and Jews—by transforming them from subjects into citizens and promising them equality with regard to property rights, education, government appointments, and the administration of justice. Encouraging their constituents to embrace the new status introduced by the reforms, Judeo-Spanish publications began to invoke the term Otomano (the translation of the Turkish Osmanlı) as an overarching designation that referred to all the empire’s citizens. Synonymous with Otomano, a new term, turkino, also entered the Judeo-Spanish lexicon and further captured the transformation of the sultan’s subjects into Ottoman citizens. In the Judeo-Spanish translation of the 1858 Ottoman penal code, the Ottoman Turkish phrase teba-yı devlet-ı âliyye (“subjects of the Sublime State,” i.e., the Ottoman Empire) was rendered as suditos turkinos (“subjects of Turkey” or “citizens of Turkey”) and referred to turkos, gregos, and djidios alike.56 When Sultan Abdülmecid I visited Salonica in 1859, for example, Saadi a-Levi composed songs in his honor that fused the language of the centuries-old prayer for the government by calling upon God to grant the sultan “everlasting salvation” with the new rhetoric that referred to the sultan’s arrival as a “festive day” for “every turkino,” in other words, all Ottoman citizens in the city.57

The diffusion of terms in the Judeo-Spanish press such as turkinos and Otomanos to describe all Ottoman citizens formed part of the broader process through which Jews engaged with and embraced the Ottoman state-promoted ideology of Ottomanism (Osmanlıcılık). The Ottoman state developed the political framework of Ottomanism to try to resolve the tension involved in the expectation that non-Muslims simultaneously express allegiance to their respective communities (millets) and to the Ottoman state, a dualism accentuated by the Tanzimat reforms.58 Ottomanism involved the promotion of political allegiance to the empire among all citizens by emphasizing a supracommunal civic nationalism, according to which non-Muslims could identify with their specific communities while simultaneously demonstrating their loyalty as Ottoman citizens. Scholars disagree over the sincerity of the project of Ottomanism on the part of state elites and whether it was doomed to fail from the start. But Ottoman Jewish leaders, who did not propose an alternative to empire, committed to the promise of Ottomanism.59

Unlike Greeks, Bulgarians, and Armenians, some of whom strove at varying points for national liberation, Ottoman Jews did not seek political independence and increasingly gained status throughout the nineteenth century as en sadık millet (“the most loyal community”). In an attempt to demonstrate their loyalty to the empire and to ensure their place as Jews and as Ottomans, Jewish leaders in Salonica, Istanbul, and Izmir orchestrated a remarkable celebration in 1892 to commemorate the four hundredth anniversary not of the expulsion of the Jews from Spain, but rather of their welcome in the Ottoman Empire. During this period, Sultan Abdul Hamid II (r. 1876–1909) abolished the recently promulgated constitution (1876–1878), imposed press censorship, narrowed the frame of Ottomanism by emphasizing Islamism, and perpetrated mass violence against Armenians (1894–1896). Fearing the fate of other non-Muslim populations, Jews emphasized their allegiance to the Ottoman state both out of sincerity and self-defense.60

Initiated from Salonica, the restoration of the Ottoman constitution and ultimate overthrow of Sultan Abdul Hamid II in 1909 provoked renewed enthusiasm for the promise of Ottomanism that sought to bind the various residents of the empire to each other and to the state. Only the shared Ottoman homeland, according to this formulation of civic nationalism, could safeguard the interests and aspirations of each “element” (unsur) that constituted the new Ottoman “nation.” Salonica’s Jews met the promulgation of the constitution with cries of biva la patria (“long live the homeland”) and yaşasın millet! (in Turkish, “long live the nation!” referring now to the Ottoman nation of which they saw themselves a part), which they integrated into their anthem, La Marseillaise Salonicienne. The Jewish poet, Jacob Yona, similarly encouraged all Ottomans to serve the “homeland” (patria): “All of the turkinos [must] be well informed: / our strength depends on being well united / great glory will [come to us] united as brothers.”61

Jewish elites continued to promote a consciousness as sivdadinos Otomanos among the Jewish masses. Jewish leaders in Salonica agreed on their support of the Ottoman state but disagreed over how it should be expressed and how to negotiate their status as citizens and as Jews. Should the Jewish Community continue to play a role in the lives of Jews? Should they preserve their communal autonomy, rely on their own courts and the chief rabbi, and participate in Jewish communal schools and philanthropies? Or should they integrate into the general institutions of the city and the state? Could and should they participate in both? Which language(s) should Jews prioritize: Judeo-Spanish, Hebrew, French, or the language of the state? Jews continued to ask these questions even after Salonica passed into Greek jurisdiction. Three principal positions emerged: integrationism, socialism, and nationalism.

Animated by Enlightenment ideals, the more secularized middle classes and supporters of the Alliance Israélite Universelle, a Paris-based educational enterprise that sought to uplift the Jews of the East and established its first boys’ school in Salonica in 1873, advocated that Jews should integrate into the surrounding society, prioritize their status as citizens, and relegate Judaism to the private sphere of religion in order to achieve full emancipation. A Judeo-Spanish expression captured this stance: djidio en kaza, ombre ala plasa (“a Jew at home, a man in public”). Self-proclaimed liberals, they advocated for the abolition of Jewish communal autonomy and separate legal status, conceived of themselves as “Jewish Ottomans,” and envisioned the Ottoman Empire as a suprareligious structure capacious enough to accommodate religious differences among its constituent populations. While a major influence in Jewish communal politics from the late nineteenth century through World War I, the power of the Alliance in Salonica waned during the interwar years.

The introduction of freedoms of assembly and of the press following the Young Turk Revolution in 1908 galvanized new political movements such as socialism and nationalism that activated additional segments of Jewish society.62 Accustomed to the concept of the millet, Ottoman Jews easily grasped the new vocabulary of nationalism, as the Judeo-Spanish term for “millet” and for “nation” was the same: nasion.63 For Jewish socialists and nationalists alike, Ottomanism did not signify a supra religious ideology that sought to accommodate Jews, Muslims, and Christians under its umbrella but rather a supra national framework to accommodate Jews, Turks, Greeks, Bulgarians, and Armenians. Blending socialism and nationalism, the city’s Socialist Workers’ Federation—the largest socialist organization in the Ottoman Empire—sought to unionize all the city’s workers across national lines, including Jews, Bulgarians, Greeks, and Turks. The Federation boasted a significant Jewish membership and leadership. As a defender of the working class, the Federation also promoted Judeo-Spanish as the language of the people. It quickly became clear during the Second Constitutional period, however, that liberation had not yet come for the working classes as evidenced by numerous strikes and the persistent domination of the bourgeoisie, including representatives of the Alliance, in Jewish communal governance.64

Esther Benbassa and Aron Rodrigue emphasize that a “variety of Zionisms” took hold in Salonica, the most prominent form of which initially focused not on the building of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, but rather on the strengthening of Jewish communal identity in Salonica itself.65 Although drawn from the middle classes like the supporters of the Alliance, Zionists opposed assimilation and the conceptualization of Jewishness as a question of private religious conscience. Zionists understood themselves as Jewish nationalists with the right to express their voice as Jews in both the public and private domains. Although embracing their status as Ottoman citizens—despite claims to the contrary by detractors, including representatives of the Alliance—they saw themselves as “Ottoman Jews” rather than “Jewish Ottomans.” They believed that Jews should preserve their communal autonomy while gaining full rights as citizens of their country. Leaders of the first Zionist club in Salonica, Bene Sion (“Sons of Zion”) initially argued that their vision of Zionism entailed Jewish cultural and national regeneration at the local level and saw the new rights introduced with the Young Turk Revolution as applying to themselves not as individuals, but rather as a collective that aimed “to develop their moral qualities, their nationality, in the world.”66

Distinguishing between political allegiance (to the state) and cultural and religious allegiance (to the Jewish nation), the Bene Sion also advocated that other Jews suffering persecution in Romania and the Russian Empire be permitted to settle in Ottoman Palestine. They argued that, by admitting Jewish migrants, Palestine would flourish economically, remain Ottoman “by sovereignty,” and become Jewish “by religion and culture.” “Our beloved homeland”—the Ottoman Empire—would again provide a safe haven for Jews as it had in the wake of the Spanish expulsion.67 But the end of Ottoman rule over Salonica in 1912 curtailed this dream. Salonican Zionists later concentrated more attention on promoting immigration to Palestine and the project of building a Jewish state there while continuing to defend local Jewish interests.

Variations of the three primary, competing Jewish ideological postures articulated on the cusp of Salonica’s incorporation into Greece—integrationism (the Alliance), socialism (the Workers’ Federation), and nationalism (Zionists)—shaped Jewish politics until World War II. New dynamics during the interwar years only compounded class divisions and cleavages between the secular and the religious. Fissures multiplied as political affiliations were overlaid upon older networks of power based on kinship and profession. Each group sought to promote its own agenda in local, communal, and statewide politics by seeking to speak on behalf of the Jewish collective. Jewish nationalists splintered into diaspora nationalists, liberal Zionists, religious Zionists (the Mizrahi), and Revisionist Zionists and battled for influence against integrationists (who referred to themselves as the Moderates) and with Jewish socialists and communists. Many Jews, meanwhile, remained politically disengaged or disenfranchised. Political differences bred animosities: Zionists denounced communists as “traitors” and the latter portrayed the former as “devils.”68 Sometimes Jewish Moderates agreed with Greek state officials that Zionists obstinately resisted Hellenization. Other times disagreements turned violent, with fistfights erupting between Jewish communists and Zionists, and with tensions spilling into nearby towns. During one Passover Sabbath in Kastoria, Revisionist Zionists and General Zionists brawled in the synagogue and choked the cantor; a hundred criminal charges were filed.69 The different political positions developed by Jews in Salonica advocated for different solutions to the predicament they confronted as they sought to accommodate their status as Salonicans, as members of the Jewish Community, and as citizens of the Ottoman Empire and subsequently of Greece.

From Ottomanism to Hellenism

With Salonica’s incorporation into Greece (1912), an ascendant vision of Hellenism displaced the established Ottomanism, further politicized dynamics among Jews and between them and their neighbors, and required Jews to reimagine their position not only within the city but also in the consolidating Greek state. Salonica had figured prominently in the Greek state’s expansionist vision, the Megali Idea (“The Great Idea”), an irredentist program that aimed to extend the boundaries of the Greek state (est. 1830) to encompass and redeem all the potential members of the Greek nation—namely, Orthodox Christians. Aspiring for imperial grandeur, the Megali Idea imagined the formation of a Greater Greece, the revival of the Byzantine Empire, and the recreation of the Greece of Five Seas.70 As the former co-capital of Byzantium and a strategic commercial node, Salonica emerged as a key stepping-stone en route to Asia Minor and ultimately Constantinople, the historical center of the Orthodox Christian Patriarchate and former capital of the Byzantine Empire. The fundamentally Greek Salonica envisioned by the promoters of the Megali Idea, however, diverged greatly from the Jewish city that they ultimately annexed. Salonica’s Jews found themselves in an unusual position as their city became central to the expansionist aspirations of Greek nationalism, whereas they themselves, by virtue of not being Orthodox Christians, were not part of that vision.

The pervasiveness of religious vocabulary in the dominant vision of Greek nationalism emerged with the war of independence itself (1821–1830). The revolutionary slogan—“fight for faith and fatherland!”—and the first constitution of independent Greece in 1822 enshrined the connection between religion and nation: “those indigenous inhabitants of the state of Greece who believe in Christ are Greeks.”71 Perhaps most dramatically, Greek Independence Day was fixed as March 25 to correspond not with any particular battle during the revolution, but with the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary. A myth of Greek national annunciation was now overlaid upon the foundational tale of Christianity.72 The intertwining of religion and national identity persisted as a key feature in the development of Greek nationalism. In the interwar years, during the Fourth of August Regime (1936–1941) that sought to fuse the values of classical Greece with Byzantine Orthodoxy, Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas appealed to already-established tropes when he promoted his slogan of Greek nationalism: “Fatherland, religion, family.”73 This kind of message remains powerful today for, as one scholar notes, “Orthodoxy is still considered to be the keystone of Greek national identity.”74

While a smaller Jewish population had inhabited largely Orthodox Christian Greece prior to 1912, their numbers increased exponentially, from fewer than ten thousand to closer to ninety thousand with the annexation of Salonica. Jews elsewhere in Greece were few, not very concentrated, and internally diverse. In 1913, for example, only 140 Jewish families lived in Athens, 100 of whom the press identified as “native,” whereas 40 were “immigrants.”75 While partly comprised of Greek-speaking Romaniote Jews, the Jews of Athens also included Ashkenazim and Sephardim. (All chief rabbis of Athens during the first half of the twentieth century were native Judeo-Spanish speakers from Izmir, Salonica, and Hebron.)76 Although the capital of Greece, Athens would remain of secondary importance in comparison to Salonica from a Jewish perspective.

Once Salonica became part of Greece, tensions between Jews and Orthodox Christians intensified due not only to their differing languages but also to enduring prejudices as reflected in continuing allegations that Jews killed Christ, periodic blood libel accusations, and economic competition. In addition, resentment lingered due to the alleged role that Istanbul’s Jews played in the execution of the Orthodox Christian Patriarch during the Greek Revolution (1821), which led to retaliatory massacres against Jews across the Peloponnese.77 Slanderous allegations that a Jew had served as the sultan’s executioner in Salonica and murdered Greek rebels during the revolution in the 1820s circulated more than a century later, in 1931, and contributed to anti-Jewish outbursts. Only when a Jewish teacher and several Orthodox Christian students at the university spoke out against the rumor was it put to rest.78 The popularity of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, translated into Greek by Makedonia in 1928, reinforced deep-seated antisemitic sentiments in Greece and provoked Jewish leaders to protest to the president of the Greek government and the Departments of Interior, Justice, and Foreign Affairs.79

In addition to the thread of Orthodox Christianity, another aspect of Greek national identity drew on the mythologies of classical Hellenism and introduced another set of tensions into the prospect of harmonious relations between Jews and Greeks. In the philosophies of the Enlightenment and romanticism, Hellenism had been imagined as the antithesis of Judaism (or Hebraism), as a world of knowledge in contest with a world of faith. In a well-known example, the nineteenth-century German poet Heinrich Heine damningly concluded that, by nature, “all people are either Jews or Hellenes,” the former tending toward “asceticism, excessive spiritualization, and image-hating,” whereas the latter “rejoices in life, is proud of display, and is realistic.80

Within the European Jewish framework, these interpretations were superimposed over other long-remembered frictions. The Jewish holiday of Hanukkah, for example, commemorates the victory of the Maccabees over their Hellenic oppressors who sought to Hellenize the Jews and forcibly assimilate them by stamping out their religious practices. In Hebrew, the verb lehityaven, “to assimilate,” literally means “to become Greek,” Yavan being the biblical toponym applied to Greece. For Jewish intellectuals inspired by the Enlightenment, Judaism and Hellenism served in modern times as ciphers for the conflict between those Jews who sought to preserve Jewish difference versus those who favored integration. Classical Greece symbolized the allure and challenge of secularism and modern culture.81

But in twentieth-century Greece, the encounter with the mythic notions of Judaism and Hellenism took on an entirely different layer of meaning initially quite removed from the European narratives. Orthodox Christian leaders in Greece preoccupied themselves not only with ideals of classical Greece but also with medieval and modern conceptions rooted in Byzantium and in Christian Orthodoxy. In fact, for much of the Ottoman period, Orthodox Christians had rejected the designation “Hellene” altogether, for they associated it with pre-Christian paganism. By appropriating European philhellenic sentiment, Greek Enlightenment thinkers developed a Greek national narrative that sought to wed the world of ancient Athens to Orthodox Christianity, Byzantium, and the Greek language in a contiguous thread of Hellenic history. The embrace of the Hellenic past also legitimized the designation of the citizens of modern Greece as “Hellenes.”82 Due to its pagan, classical antecedents linked less to Christianity than to Europe and the Enlightenment, the more secular framework of Hellenism seemed more appealing to Jewish intellectuals in Salonica seeking to carve out a place for themselves and their community in modern Greece. The task at hand would be to discover ways to reconcile Judaism and Hellenism, both the mythologies and the twentieth-century realities.

Because the Megali Idea aspired to transform Greece into a new empire, Greek statesmen incorporated imperial sensibilities into their brand of Hellenism that, for practical reasons, relied on legal structures and categories bequeathed by the Ottomans. In effect, Hellenism incorporated elements of Ottomanism in order to accommodate Judaism. At the height of the hope for continued Greek expansion into Asia Minor in 1920, the Greek state recognized the Jews as a religious minority and reconfirmed the status and structure of the Jewish Community of Salonica as it had existed in the late Ottoman era. Jews gained recognition as a kind of neo-millet, along with the Muslims in Thrace—a status now legitimized by reference to Hellenism and minority rights as promoted by the League of Nations.83 That status did not go away with the end of Greek imperial aspirations following the expulsion of the Greeks from Asia Minor in 1922 and the concomitant dissolution of the Megali Idea. Especially following the establishment of the Hellenic Republic in 1924, the Greek state embarked on a more thorough and forceful nation-building project to Hellenize Salonica and all the New Lands acquired since 1912. But this nationalizing process coexisted with imperial-style dynamics as the Greek state continued to recognize the separate legal status of the Jewish Community.84 Hellenization emerged as a prolonged process that involved continued negotiation between the state and the city’s Jews—and the formal Jewish Community—as well as a variety of other populations in the region.

Administrative echoes of the Ottoman Empire persisted in the manner in which the Greek state simultaneously preserved the differentiated, collective, legal status of the Jewish Community while also seeking, however haltingly, to transform individual Jews into citizens. Tensions abounded. Although asked to serve in the military and increasingly to speak Greek, Jews were compelled to vote in a separate electoral college (1923–1933) in order to minimize their influence on Greek elections, were not permitted to marry non-Jews except through a ceremony abroad or following conversion (civil marriage did not exist until 1982), and remained under the surveillance of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Although the Greek foreign minister endorsed the creation of a Jewish national home in Palestine, the Greek state recognized its own Jewish citizens as a religious minority. Such processes of differentiation implemented by the Greek state did not prevent the Judeo-Spanish press from imagining Salonica’s Jews as an integral part of the “Hellenic people” (puevlo eleno) bound by shared territory and citizenship if not religion or ethnicity.85 This vision of Jewish Hellenism in interwar Salonica, reflected throughout this book, defined Hellenic citizenship according to the principle of jus soli (based on residence) rather than jus sanguinis (based on descent or national/ethnic membership).86

The adjustment from the Ottoman to Greek frameworks, from the world of Ottomanism to that of Hellenism, therefore not only presented Salonica’s Jews with an immense, unprecedented set of challenges but also offered them unexpected opportunities. Scholars typically identify three demoralizing turning points amidst this transition. First, a crippling fire in 1917 left seventy thousand of the city’s residents homeless, including fifty thousand Jews, and destroyed thirty-two synagogues, as well as numerous Jewish clubs and associations, schools, libraries, and communal archives. Regarding the fire as “providential” in order to impose a new, modern, European, and Greek urban plan, the state prevented the fire victims from rebuilding their homes and institutions in the city center, which had served as the heart of Jewish life for centuries.87

Second, under pressure from Orthodox Christian refugees from Asia Minor, the Hellenic Republic introduced a Sunday closing law in 1924 allegedly to level the economic playing field. The law overturned the long-standing custom not only among Jews but the entire city to rest on Saturday in observance of the Jewish Sabbath. Finally, in the context of the depression in 1931 and spurred by accusations made by a major Greek newspaper (Makedonia) that Jews were disloyal to the state and enemies of the Greek nation, a mob led by the right-wing National Union of Greece perpetrated the first major anti-Jewish attack in Salonica’s history, the Campbell pogrom, which resulted in a Jewish neighborhood being burnt down. The perpetrators were never convicted, and the series of events eviscerated the widely held image of Salonica as a Jewish safe haven.

Although each of these events undermined the status of the city’s Jews and provoked waves of emigration, they did not entail the inevitable dissolution of Jewish life in Salonica. Rather, each event compelled Salonica’s Jews to develop new forms of political and cultural engagement in order to retain a sense of Jewish collectivity, to solidify their connection to the city, and to foster a sense of belonging to the Greek polity. In the wake of the fire of 1917, the editors of El Puevlo, which became the most important Judeo-Spanish newspaper in the city, launched their first issue in order to “return our great community to its flourishing state as it had been” prior to the fire and to “assure the future of the Jewish people” in the city.88 El Puevlo argued that the fire, although disastrous, would provide an opportunity to create a “new Community,” more democratic and more efficiently run.89

While the Sunday closing law of 1924 overturned the legendary status of Salonica as the Shabatopolis, or city of the Sabbath, Jewish leaders did not resign themselves to the imposition of the new law. The Interclub Israélite, an umbrella group representing thirteen of the most prominent Jewish associations in Salonica, submitted a petition to the League of Nations, via the Board of Deputies of British Jews in London, arguing that the Sunday closing law violated their minority rights protections.90 But their efforts were not successful. Back in Salonica, the Shomre Shabat (“Guardians of the Sabbath”) organized two thousand members to convince many Jewish shop owners to observe the Sabbath by choice. The rabbinical court further brokered compromises with Jewish merchants that permitted, for example, a Jewish butcher to open his shop on Saturday mornings to sell to Christian clients and initiated what the press referred to as “modern Shabbat,” which promoted more harmonious relations with non-Jewish neighbors.91

Finally, despite—or perhaps because of—the anti-Jewish Campbell attacks in 1931, representatives of the Jewish Community, the Zionist Federation of Greece, and the Club of Liberal Jews joined rallies at St. Minas Church in support of the “union” (enosis) of Cyprus to Greece later the same year. “In our quality as Hellenes,” the Jewish representatives proclaimed, “we have, with all of Hellenism, protested to the Nations to recognize the sacred will of the Cypriotes.” In response, the National Organization of Greek Army Veterans praised the declarations of Salonica’s Jews, who “revealed their Hellenic soul.”92 Were these expressions of genuine patriotism or artificial, self-defensive loyalty—or both?

The most prominent Greek statesman of the twentieth century, Prime Minister Eleftherius Venizelos, urged Salonica’s Jews to go beyond pledges of political loyalty and follow the example of their Romaniote coreligionists if they were to guarantee a place for themselves in Greek society. A few thousand Romaniote Jews had resided in Greek-speaking lands—most notably Ioannina, in Epirus—since antiquity (since the Roman era, hence their name), spoke Greek fluently, gave their children Greek names, and, as Venizelos saw it, expressed their Judaism exclusively as religious (rather than national) difference.93 Venizelos offered an ostensibly liberal promise that echoed features of Greek Enlightenment thinker Rhigas Velistinlis’ unrealized eighteenth-century vision for a pluralistic Hellenic Republic inclusive of Greeks, Serbs, Bulgarians, Vlachs, Armenians, Jews, and Turks—all bound together by shared Greek language and civic responsibilities.94 If Jews adjusted their cultural and political orientation, Venizelos suggested, they would become Hellenes and be accepted as such. In this regard, Salonican Jewish Ottomanism and Hellenism diverged concerning the role of language: while Turkish never assumed the role of the dominant Jewish language prior to 1912 within the framework of Ottomanism, once the city came under Greek rule, Greek moved to the center stage and challenged the position of Judeo-Spanish, Hebrew, and French. This language, it was hoped, would provide the glue to bind Jews to their Christian neighbors—many of whom, including refugees from Asia Minor, were also learning Greek—and to the state.

Seeking to carve out a space for themselves in Greece, Salonica’s Jewish elite appealed to a definition of Hellenism modeled on their understanding of ancient Athens, its proverbial liberalism, and emphasis on civic belonging. In place of the Ottoman-Jewish romance that revolved around 1492, Jewish leaders developed new narratives about the centrality of Salonica to Hellenic history and the key role played by Jews in that history, dating back to the first century, when the apostle Paul preached at the Romaniote synagogue in Salonica. They emphasized the complementarity—rather than the antagonism—between Hellenism and Judaism, philosophy and monotheism, which they construed as the dual founts of modern civilization. Endorsing nationalist narratives, they fashioned present-day Jews and Greeks as the cultural heirs and genealogical descendants of Moses and Plato. The Judeo-Spanish press even claimed, by reference to the fourth-century Greek historian Diodore, that Jewish presence in Greece dated to the era of Moses: those Jews who did not follow him to the Promised Land settled in Greece.95 Zionists patterned their own efforts for Jewish national liberation in Palestine on Greek nationalism, the success of which they viewed as a model and inspiration for their own aspirations, a project they referred to as their own “great idea” (la grande idea). Salonican Zionists did not consider their desire to create a Jewish state in Palestine to negate their simultaneous pledges of allegiance to Greece.96

The well-known journalist, member of Greek Parliament, and leading figure in Salonica’s Zionist movement, Mentesh Bensanchi, insisted that there was no contradiction between being a Hellene and a Jew. This was because he envisioned the Hellenic polity “as truly liberal”—a country that, if true to the ancient liberal Hellenic spirit, would recognize and respect cultural and communal differences among its citizens. In this version of Hellenism, Jews and Orthodox Christians equally warranted their status as Hellenes, whether as “Hellenic Jews” (djidios elenos), “Jewish Hellenes” (elenos djidios), or “Hellenic citizens of the Israelite confession” (citoyens hellènes de confession israélite). Ultimately, visions of civic Hellenism, just as Ottomanism before it, sought to resolve the tensions embedded in the preservation of Jews’ dual legal status as citizens of the country and members of the Jewish Community. After Greece annexed Salonica, rather than abolish the Jewish Community, the state reconfirmed its legal status and ironically incorporated it into the process of Hellenization. In essence, the challenge posed by Jews in interwar Salonica was not that they unequivocally resisted Hellenization, as scholars often suggest; rather, they articulated a different vision of what Hellenization could become. Was it in vain that, referring to mother Greece and her Christian and Jewish citizens, Bensanchi asked: “Can a mother not love her many children?”97 Even if the state appeared willing to embrace its varied citizenry—if the mother could embrace her Jewish and Christian children—would those children be willing to accept each other as siblings?

The chapters that follow trace key dilemmas confronted by Salonica’s Jews that reflect their attempts to navigate the transition from the Ottoman Empire to modern Greece, from the 1880s until World War II. The first chapter explores the creation and development of the institution of the Jewish Community of Salonica. Due to the largely self-governing status of the Jewish Community, everyday Jews relied upon it—as if it were a municipality or a state, as one commentator observed—to endure the tumultuous transition from Ottoman to Greek jurisdiction, including war, fire, and economic crisis. Sometimes in conflict and other times in partnership with the state, the Jewish Community defined its members, subjected them to Jewish marriage law, managed Jewish popular neighborhoods for the impoverished, and facilitated the induction of Jewish men into the army. Allegiance to the Jewish Community and to the state sometimes complemented each other, whereas other times they stood in opposition.

The ongoing debates over the role and nature of the spiritual and political leader of the Jewish Community, the chief rabbi, forms the heart of the second chapter. Deliberations among competing Jewish political factions over the nature of the position of the chief rabbi reflected their differing values and contested visions for the future of Salonica and its Jewish residents from the late Ottoman era until World War II. While Jewish political groups largely agreed that the chief rabbi ought to represent the city’s Jews to their neighbors, the state, international organizations, and Jewish communities abroad, they often disagreed over who the chief rabbi ought to be and what kind of image he should project to the world about the status of the Jews of Salonica.