THE IDEA OF WRITING ABOUT monuments from colonial-era Algeria first came to me in Lyon, France on November 11, 2013, during Armistice Day commemorations, as former settlers of French Algeria were singing “The Song of the Africans,” their unofficial anthem,1 and I was contemplating the statue of an Algerian soldier whose bust was fused to his Senegalese and French counterparts (figure 2). I am rehearsing Edward Gibbon, who, in his autobiography, describes the epiphany that inspired the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, “at Rome on the fifteenth of October 1764 . . . amidst the ruins of the Capitol, while the barefooted friars were singing Vespers in the temple of Jupiter.”2 In Gibbon’s Rome, preserved Roman ruins attest to the destruction of an empire, to a Christianity triumphant over paganism, and to materials cannibalized for new structures. My own epiphany evidenced the same fascination with the melancholic ruins of an empire’s transported and renewed materiality. Where Gibbon was contemplating the vestiges of Roman ruins, I was looking at the World War I war memorial to soldiers from Oran, Algeria, who had fought for France. This colonial vestige from Algeria had been moved to the northwest quadrant of Lyon, France, the arrondissement of La Duchère, a neighborhood created after World War II. During my year of research in Lyon (2013–2014), I learned that the three soldiers atop the memorial had been removed from their base in 1968 and brought to Lyon to be placed in a new district for European settlers who had left Algeria in 1962 at its independence from France. Every year, Lyon’s Oran monument attracts former settlers from Algeria who, like their monument, come from a dismantled French colonial empire.

I wanted to analyze French colonialism and its aftermaths in France and Algeria through war memorials, the “monuments after all” that survive in both countries.3 They are the many visible aspects of French colonialism, and since 1962, when Algeria won its independence from France, are among colonial artifacts in France as well. Standing before Lyon’s war memorial from Oran, I wondered how, why, and when a war memorial bearing the name of Algeria’s second largest city came to a new public square in Lyon. Since when did France’s Armistice Day commemorations for the dead soldiers of World War I and World War II include ceremonies for Algerian Muslim auxiliary troops who fought against Algerian independence?4 Which actors are safeguarding the patrimony of French Algeria amid the noisy claims of ownership over the patrimony of the source community to whom this colonial statue of Algeria in France putatively belongs?

My reactions to this peculiarly placed Algerian monument in Lyon reflect my deep attachment to the city of Oran, Algeria. These responses to Lyon’s statue are a formative condensation of happy memories from when I lived intermittently in Oran between 1990 and 1992 and discovered my strong affinity for the place, my research subject, and met the man whom I married. During those two years, I often walked by the Stèle du Maghreb (figure 3), which sat prominently on the palm-lined corniche overlooking the Mediterranean bearing an explanatory dedication by the Algerian poet Moufdi Zakaria. I had assumed it was Oran’s war memorial that commemorated the Algerians who had died fighting for independence from France during the Algerian War of Independence (1954–1962). On its plinth and column had stood three sculpted soldiers that were now in Lyon.

In two different countries at different times, I confronted at least two monuments, or two different parts of a single monument: in Oran, the footprint and pediment that had formed the base of the 1927 monument were still traceable at the original emplacement; in Lyon, three sculpted World War I soldiers symbolized those who had fought and died for France. What I glimpsed then in Lyon and had previously seen in Oran shaped my understanding of the monuments that filled the Algerian landscape. These memorials, columns, cenotaphs, pillars, crosses, and statues were not merely aesthetic creations; they were a structural component of colonial French power and violence. Bold, confident, intrusive monuments stood on land that had been allocated by a succession of French military governors to the largest European settler colonial population among France’s overseas colonies. They adhered to French canons of beauty and civic order and signified the territorial dispossession of the colonial native subject. Algeria’s history as a French colony from 1830 to 1962 is written in and by an abundance of statues and war memorials built for and by Algeria’s European settler colonial population. Their story—how, where, why, and how many were built under colonial rule and what happened to them at Algerian independence—is told in this research across detailed case studies. Monuments are important for visual and written records of the history of France in Algeria; indeed, a study of the region could “start with art.”5

A monument was erected to France’s 1830 invasion of Ottoman-ruled Algiers that began 132 years of French colonial rule over Algerian territory. On the Mediterranean coast just west of Algiers, a massive amphibious French military force of 37,000 soldiers and 27,000 sailors landed at Sidi Fredj, vastly outnumbering the 3,000–5,000 Algerian troops. They were the first wave of France’s murderous military campaigns, which continued until the defeat of the great nineteenth-century Algerian resistance leader, the Emir Abdelkader (ʿAbd al-Qādir ibn Muḥy al-dīn, 1808–1883) in 1847. At his surrender, the French army in Algeria numbered over 100,000 men. A hundred years after the French landing, a fifty-foot monument was erected to commemorate the centennial festivities of French Algeria in 1930 on that spot at Sidi Fredj—the Arabic name which became colonial Sidi Ferruch.

Sculpted by Algiers-born artist Émile Gaudissard (1872–1956), the monument depicts a standard-bearing allegorical female France embracing a smaller female Algeria counterpart. The inscription summarizes France’s imperial “mission to civilize” (mission civilisatrice):

Here on the 4th of June 1830/ By the order of King Charles X /under the command of General de Bourmont / the French Army / came to unfurl its flags / liberating the seas / giving Algeria to France / 100 years later / the French Republic / having brought justice to this country / a thankful Algeria / pays homage to the mother land / the homage of its everlasting attachment.6

The Sidi Fredj / Sidi Ferruch sculpture bookmarks the existence of French Algeria—the victorious invasion of 1830 celebrated at its centenary of 1930, and the 1962 Algerian independence celebrations when joyous Algerians chiseled away the monument’s inscription (figure 4). Just before Algeria’s official independence day of July 5, 1962, the French military swiftly dismantled Gaudissard’s monument. Sections of it now sit in an outdoor museum complex in France’s southwestern Mediterranean port of Pont-Vendres, facing Algiers.7

France’s conquest of Algeria was commemorated by monuments that were erected everywhere and on a grand scale. War memorials outnumbered the monuments to great men. Approximately 36,000 war memorials were erected in France, which included Algeria (integrated as France’s southern departments or provinces) and in its other overseas colonies.8 “Statuomania” refers to these vast numbers of statues including those brought to the Algerian colony.9 The practice of systematically recording and identifying by name the dead in military cemeteries began in France after World War I even as local war memorials provided sites for mourning and remembrance by families bereft of loved ones who were buried on distant battlefields.10 French war memorials were first erected in large numbers after the Franco-Prussian war and continued for the two world wars; war memorials began appearing in large numbers in Algeria after World War I. Conquered Algerians could see an unprecedented number of statues and monuments—three-dimensional representations that shaped them into a “picture-minded people.”11 Historian Arthur Asseraf claims that the groundwork for visual literacy was laid even among illiterate Algerians by the vast output of illustrated newspapers and magazines in circulation in the colony between 1881 and 1940 at the height of French colonial power.12

A war memorial was part of the template for a French town center. These omnipresent monuments were integral parts of most settler town layouts in French Algeria in the interwar years, if not earlier—the towns are unimaginable without them. Monuments were typically sited adjacent to the colonial military-prison complexes that protected settler spaces. Immediately after World War II, another generation of war memorials was erected in France and its colonies; these were new memorials, or occasionally simple additions to the World War I monuments inscribed with the names of newly fallen soldiers. Where erecting these monuments in France was a ceremonial sign of postwar bereavement, erecting them in Algeria was a material expression of colonialism as a state of war to eliminate the native population and their claims to land. These monuments, war memorials, and statues erected by French imperial power in settler colonial contexts—a legacy of French statuary—were later reshaped by Algerian decisions about their fate and existence. Modified in contemporary postindependent spaces of Algerian towns and villages, the street grid often converges on a central square bordered by a former church, a post office, a municipal building, a school, and a war memorial. After Algerian independence, during the decade of the 1960s, many colonial-era memorials were rededicated to the Algerian War of Independence.13

The history and context of many French colonial monuments must also account for the removal of some or some parts of war memorials from Algeria to France, processes tied to the different communities in the colony. The dramatic exodus of most European settlers began in the early 1960s after a war of independence that lasted seven years (1954–1962) followed by massive departures from Algeria. This exodus reversed the nineteenth-century arrivals of Europeans, and also, in part, the implantation of commemorative French monuments. The defeated French army returning to metropolitan France, the Catholic Church whose properties and personnel were reduced, and individual settlers all played a role in uprooting these particular signs of French domination. Military and colonial archives attest to the many ways that colonial monuments were moved out of Algeria, destroyed, or replaced. They never explain why. It is settler colonial studies that provide theoretical approaches that confront French ideas, in contrast to Algerian ideas, to understand these as acts of patrimony, what it means when people move with their objects across the Mediterranean. The displacement and removal of communities and things are part of the colonial legacy that endures long after Algerian independence and affects French and Algerians in fundamental, visible, and quotidian ways. In France and Algeria, commemorative war memorials trigger a nostalgia for and a memory of French Algeria that binds Algeria and France materially and emotionally.

To regulate the end of the Algerian War of Independence and the loss of France’s last North African colony, the Évian Accords of March 18, 1962, stipulated that by July 5, 1962, the French army would leave most of independent Algeria, with the exception of its military sites in the Sahara.14 But to insure an orderly removal of archives and monuments, approximately 80,000 French troops remained for twelve months at Oran’s nearby naval base, Mers-el-Kebir. France negotiated an additional fifteen-year lease for the naval base to make it easier to transport people and objects out of Algeria, which ended earlier by 1968.

In the first years after Algerian independence, two-thirds of the settler population of some 1,300,000 people—the majority of whom were French citizens—departed. More than half left between January 1, 1962, and December 1963.15 They and their artifacts were “repatriated” to France. Where the departing settlers were legally deemed repatriates, their artifacts were not. Depending on highly divergent definitions of the term “repatriation,” the removal of artifacts was considered legal or spoliation. “Repatriate” was initially defined by the French law of December 26, 1961, as applying to a specific trans-Mediterranean mobility of French persons from former French colonies: “Those French, having had to leave or feeling obliged to leave because of political events, a territory in which they were established and that had previously been under the sovereignty, protectorate or trusteeship of France.”16

The new set of laws to support the “repatriates from Algeria” (rapatriés d’Algérie) conferred legal and political legitimacy and provided state financial indemnification, housing allocations, and more in France. Those who fled Algeria precipitously might have been deemed exiles, asylum-seekers, refugees, migrants, emigrants, expatriates, or immigrés (immigrants) in a diaspora, but the only designation for those migrating post-1962 with their belongings across the Mediterranean—to France in the main, but also to Spain, Malta, and Corsica—ever to have stuck was repatriate.

Colonial settlers were not the only group of “repatriates.” Counterintuitively the majority of native Algerian Jews, who had been granted French nationality by the 1870 Crémieux Decree, were also considered repatriates. This rare extension of French citizenship to an entire Indigenous religious community in a settler colonial setting enabled Algerian Jews to integrate French institutions such that by the time of the Algerian War of Independence and definitively by the time of their exodus in 1962, the autochthonous Jewish community (israélite indigène) was assimilated into the category of pied noir, the popular term for the settler colonialists of European descent.17

While most historians believe that the term pied noir emerged post–World War II, its origins are numerous and colorful.18 It has been translated literally as “black foot,” associating the European settlers with the Native American tribe of the same name or with the black military boots of the conquering French army. Others considered that settlers blackened their feet with their grape-trampling winemaking.19 My preference is for Pierre Bourdieu’s definition of pied noir as a deformation of pionnier (pioneer) and a pure creation of French Algeria, in keeping with the approach taken in settler colonial studies: “There is a good deal of unfairness in the attitude of these Frenchman who make the pieds-noirs their scapegoats and blame all the tragic happenings in Algeria on their racism . . . it is colonial Algeria that has produced the pied-noir and not the reverse.”20

In this study, I replace the French lowercase italicized pied noir into the English uppercase hyphenated Pied-Noir to designate them as a group and a community marked by their historical, geographic, and communal upheaval. I use “Pied-Noir” as the indexical term to reference the vast literature on social agents, affective continuities, and material objects written about and by all the European settlers post-1962 who left for France, and that also encompasses the native Algerian Jewish community.

These repatriates—European settlers and Indigenous Algerian Jews—received social benefits, relocation subsidies, and social services; unlike a third group of Algerian Muslims who had fought for the French during the Algerian War of Independence but could not be considered repatriates and indeed received few benefits.21 Sometimes subjected to retaliation by Algerians during and at the end of the war, they were labeled refugees in France. While they did eventually become French citizens, they were designated citizens called “French of North African origins” (français de souche nord-africaine, FSNA) and endured social marginalization in France.22 The colonial Muslim indigène retained the name of Harki brought from Algeria to the metropole but was affected by evolving legal designations and practices. These boundaries of French Algeria’s populations on which constantly changing legal practices rely and get defined have recast the colonial Muslim indigène in the colony as the Harki in the metropole. As historian Lorenzo Veracini emphasizes, settler colonialism projects a future of a society to come.23 Even “repatriated” to France, the settlers’ ideas about settlement and Indigenous peoples matter: just as they could not imagine their place in a future Algeria without a vocabulary that was specific to French Algeria, so too, categories for the Harki were fixed when in France.

The former French colonial populations of the provinces of Algeria reconfigured their stories of group belonging and formation by 1962. Their repatriation implied an ingathering of settlers as opposed to a diaspora. Settlers who had gathered in French Algeria subsequently gathered in France where they retained their identity as settlers, having brought with them their statues. They had arrived in the hundreds of thousands as settlers and colonists on North African shores as of the early nineteenth century as migrants; their decolonization became what anthropologist Andrea Smith calls the story of an invisible return—of people coming “home,” propelled by postindependence political tumult not only in Algeria but also in the formerly French North African colonies of Morocco and Tunisia.24 These European settler repatriates of Algeria comprehended their chronologically divided and distinct existences on two shores of the Mediterranean Sea through doubling, repetition, and reinvention. From 1961 to 1963, the end of French Algeria and the first years of Algerian independence, the European settler community that departed Algeria en masse referred to the experience as a “loss” (perte), “exodus” (éxode), “wounds” (blessures), and “wrenching heartbreak” (les déchirements). Similarly, after the sea crossing, the Pieds-Noirs use an imagined binarism characteristic of settler colonial contexts according to Patrick Wolfe.25 In various interviews, they told me that they find themselves exiled in the metropole although they are français d’outre-mer (overseas French); they are “here” or ici in France versus là-bas, “over there” in Algeria. They live among français de souche (original French stock) rather than among themselves as Pieds-Noirs who may be français de racine (of French roots) or français de coeur (emotionally French). Time is laid out in futureless contrasts between actuellement and anciennement (currently and formerly; life in France and life in French Algeria), their official status as “repatriated” versus éxil and exode (popular expressions of “exile” and “exodus”), where they live in pays d’adoption versus pays natal (an adopted country versus land of birth). While this may not be surprising to anyone who has shifted countries, the fiction of legal repatriation is that they moved back home.

Repatriation as a process and explanation undertaken and given by French colonialism lives uneasily with theories of decolonization demanded by an independent Algeria. Where material and geographical studies examine ongoing settler colonies in the United States, Canada, and elsewhere, the native Algerian and the European settler interacted and navigated colonial power in physical spaces that were sundered in 1962: French occupation and the settler colony in Algeria were no more. Settler colonialism is a structure, insists historian Patrick Wolfe, and the mass exodus from Algeria to France that created repatriates but preserved the settlers intact, even as they vacated, will be investigated in this study as innovative structures. And a statue is literally a structure meant to be looked at.

Rescue strategies for French Algeria’s objects were integral to the chaotic events during that first year of independence marked by violence and fear on all sides.26 The exit of French imperial power from the decolonized spaces of Algeria throughout the decade of the 1960s included messy moves and removals of people, monuments, sculptures, and objects. For now, the term “removal” shies from calling out the legality of the move, by and for whom. Whereas the removal of French war monuments from Algeria to France was called repatriation, no legislation covered it or addressed the monuments. The 1962 Évian Accords that negotiated Algerian independence did not mention these monuments. The term rapatrié, much too vague after its original collective designation of human beings, was borrowed and applied to objects and statues and even actions. But its application to cultural objects was contested as perceptions and definitions of this “repatriation” ranged from destruction or spoliation to preservation to reuse. Moreover, most removals were undertaken without consulting the provisional Algerian government. They became integral to the wrenching experiences of decolonization and exile from the lost settler colony. This special category of monuments taken/repatriated from French Algeria to France includes colonial statues, church bells, and war memorials uprooted from their original sites. Their removal during the waning years of France’s control of its overseas provinces of Algeria reflected among other things the belief that the French monuments faced imminent destruction from a newly sovereign Algerian state during this major geopolitical rupture. In response, many institutions and networks in France and the colony were activated to remove them. The French army and navy coordinated their passage across the Mediterranean Sea. Repatriates took them as they departed. Public art moved out of Algeria was designated rapatrié to hide the economic processes and complex transnational circuits through which large artworks were dismantled, packed, and transported from Algeria to their presumed place of origin in France. There, they were installed in new sites of colonial memory in France making parts of France into a memorial for its own settler colonial monuments and settlers. A major geopolitical rupture, a French belief that the monuments faced destruction from an independent Algeria, and the capacity and will to transport them elsewhere by the “repatriated” drove this.

Contemporary heritage standards require that objects be identified by their provenance, which entails a history of their creation and custodianship. Subsequent chapters of this study will revise French metropolitan descriptions of Algerian destruction of statues on the basis of information from the military archives housed at the Château de Vincennes near Paris, a major point of collection and dispersal for removed Algerian monuments. There among the file boxes, I found documents with clearly articulated objectives for the “repatriation of souvenirs militaires,” where souvenir denotes “monument.”27 Documents laid out the plans to have the French army remove preemptively monuments in January 1962, six months before independence. Box 1R 368 of the French military archives delineates a roadmap for monument removal, although oral consultations among military and ministry staff typically preceded written directives in all likelihood. Protocols were thus charted months before the March 1962 ratification of the Évian Accords separating France from Algeria and before the July 1962 countrywide referendum that confirmed independence.

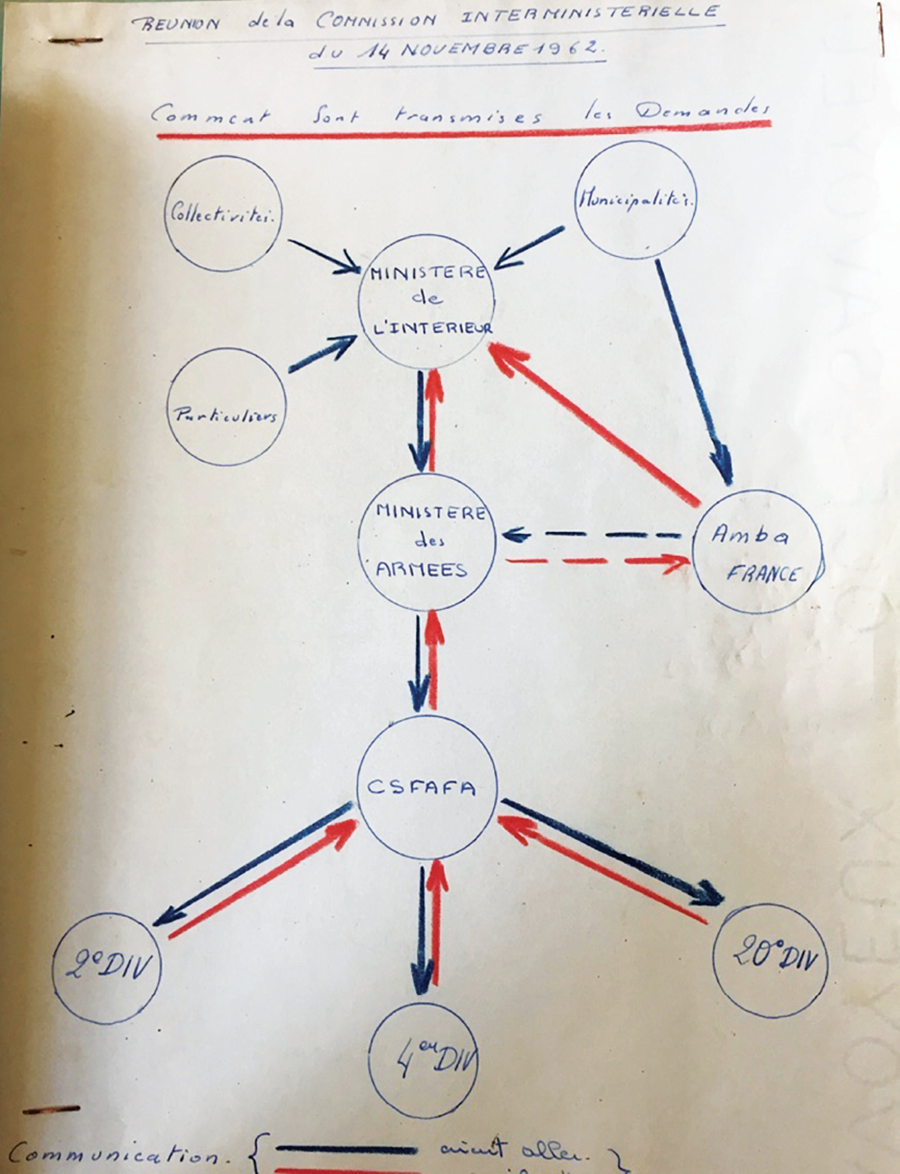

Correspondence between the headquarters of the Ministry of Armies and the Superior Command of French Forces in Algeria (CSFAFA) to local commanders throughout Algeria involved requests for lists and descriptions of monuments on the blank forms (fiches descriptives) that were provided. These included indispensable war memorials and sculptures slated for shipment to France. The combined military forces of the French army, navy, and engineering corps were instructed to cull objects and statuary deemed important for safeguard, preservation, and transportation to France. A diagram limns the military decision-making hierarchy (figure 5). Red, blue, and black lines and circles delineate the central roles of the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of the Armies. Information about proposed monument removals was collected from municipalities, collectivities, and individuals in coordination with the French Embassy and transmitted to central command headquarters. Three army divisions were put in charge of removals and transport at monument sites corresponding to Algeria’s three French départements: the 20th division for central Algiers Province, the 4th division for western Oran Province, and the 2nd division for eastern Constantine Province, all reporting back to the central command.

So, in the months before official independence, the military established bureaucratic avenues and infrastructural networks to remove monuments. In addition, museum contents were also slated for “recuperation.” The Laclotte Mission of July-August 1961—named for art historian and museum director Michel Laclotte (1929–2021)—surveyed Algeria’s museum riches and advocated for art objects.28 Concurrently, the settler population was aided by the colonial civil bureaucracy in retreat even without the support of the French army or top-down military instructions to undertake private initiatives. For objects, “repatriation” was seen to entrench rights to artifacts from the colony by settlers, who became France’s metropolitan repatriates.

In France and Algeria, the demise of colonial North Africa promoted new heritage-formations and performative ceremonies. Augmented, repurposed, saved, de-territorialized, or destroyed monuments become emblematic of settler colonial, postcolonial, and decolonization worlds. When we look upon such monuments that seem to speak to material processes of hybridity, resistance, mimesis, or assemblages, we also look at the shared desires of former settlers and the formerly colonized to safeguard and preserve. In many ways, which this book explores, Algerian statuary and monuments participated in the colonial encounters that had reconfigured the North African littoral into French overseas provinces (départements) for 132 years.29 Altered and removed, the monuments, statues, and war memorials took on unintended meanings, were seen in new ways, and became new objects. Many colonial-era plinths, pedestals, and figurative sculpted representations confront viewers in both countries to this day. They arrive before our eyes as the contemporary terminus ad quem, “the limit up until which,” that signals the decolonization process, wholly or in part, whether by removal or patrimonial preservation.

Monuments, it seemed to me, were essential to French urban life.30 I was living in Lyon in 2013–2014, at a time when the city was considering its long-standing local involvement in preserving and restoring ruins. Issues of patrimony had long been gaining currency. Three international charters—the 1931 Athens Charter, the 1964 Venice Charter, and the 2000 Krakow Charter—have declared that “the question of the conservation of the artistic and archaeological property of mankind is one that interests the community of the States, which are wardens of civilization.”31 Such guidelines for preserving monuments in or outside national boundaries reflect assumptions about the general value of artifacts of civilization. The complexity of the issues has led to many additional agreements, charters, and conventions: the Moveable Cultural Property Convention (1954), the Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property (1970), also articulated in the World Cultural and Natural Heritage Conventions (1972). In the aftermath of World War II, UNESCO established the transregional Tunis-based ALECSO (Arab League Educational, Cultural and Scientific Organization) for the Middle East and North Africa in 1970. A set of rules evolved to insure, protect, and when possible, enforce “the layered metacultural operations that constitute heritage in the first place—the host of regulatory steps, actors and institutions that transform a cultural monument, a landscape or an intangible cultural practice into certified heritage.”32

From such official (and culturally contingent) contexts, nation-states interacting with international bodies define patrimoine whose semantics range from “cultural property” to “history” to “inheritance,” less commonly “patrimony,” and often as “heritage” or “cultural heritage.” These words effectively designate what many inhabitants of Lyon regard as their patrimony with its double links to France and to Roman Lugdunum. French Algeria’s artifacts thus belong to European settlers who trace a long line to Rome. The preservation of objects and shared values and collective memories constitute patrimony or heritage, according to cultural theorist Robert Shannan Peckham, in his terms:

On the one hand, [heritage] is associated with tourism and with sites of historical interest that have been preserved for the nation. Heritage designates those institutions involved in the celebration, management, and maintenance of material objects, landscapes, monuments and buildings that reflect the nation’s past. On the other hand, [heritage] is used to describe a set of shared values and collective memories; it betokens inherited customs and a sense of accumulated communal experiences that are constructed as a “birthright” and are expressed in distinct languages and through other cultural performances.33

But Algeria and France have opposing (and overlapping) notions of patrimony. For architectural historian Nasser Rabbat, patrimoine in Arabic has a “lost-in-translation effect,” in which the word turāth connotes “inherit.” 34 Thus, it may include French colonial artifacts. On the eve of Algeria’s hard-fought independence from France, the National Council of the Algerian Revolution (Conseil national de la révolution algérienne, CNRA) adopted the “Tripoli Program” to embed Algerian heritage in a culture of resistance such that the quest for freedom and independence intersected with heritage insofar as the civilization was said to support national resistance. The Arabic language needed to be returned, having been endangered when French was the designated official language of colonial Algeria.

[Algeria’s] economic prosperity, the exceptional vigor of its people, its traditions of struggle, the fact that it belongs to a culture and civilization common to the Maghreb and to the Arab world, have all long supported national resistance. . . . . The necessary creation of a political and social mindset informed by scientific principles and fortified against erroneous ways of thinking makes us appreciate the importance of a new conception of culture. Algerian culture will be national, revolutionary, and scientific. As a national culture, it will in the first place be about returning its dignity and effectiveness as a language of civilization to the Arabic language, the very expression of our country’s cultural values. To do so, it will endeavor to reestablish, revalorize, and promulgate the national heritage and its twin classical and modern humanism in order to reintroduce them into the intellectual life and education of the population’s sensibility.35

Patrimoine is thus a form of cultural resistance against the colonial European elimination of local languages and the reinvigoration of Indigenous approaches to ethnographic research that had come under attack during the French colonial era.36

To discuss patrimoine in Algeria, architect Yassine Ouagueni uses the image of phased house building. Just after independence, legal ordinance number 67-281 of December 20, 1967, called for protecting historical sites and monuments. Ouagueni dates the more substantial concern for Algeria’s cultural heritage to Law no. 98-04 of June 15, 1998, which complemented or extended legislation.37 Law no. 99-07 of April 5, 1999, added a historical and cultural heritage regime or set of rules when it amended the privileges and rights of fighters and martyrs of the Algerian revolution. Articles 52–54 identified commemorative stelae and specific sites as national revolutionary symbols that included torture centers, forced regroupment camps, prisons, battles, archives, and films. It mandated the preservation of this material historical patrimony, or heritage: “it is prohibited to transfer, in whatever form, parts of historical and cultural heritage.”38 The initiatives also include Executive Decree no. 03-322 of October 5, 2003, on protected cultural elements; the Decision of May 29, 2005, establishing interventions for protected cultural elements; the Decision of May 31, 2005, providing a list of interventions on protected cultural elements; and the Decision of November 5, 2007, to pay the costs of interventions of protected cultural elements. For Ouagueni, these initiatives raised questions about the concern for patrimony and its protection:

In other words, it is appropriate to ask when and why this idea [of patrimony] arose in the daily life of Algerians: Was it driven by colonization? Did something entirely new emerge at specific moments of the post-colonial period? Should we see it as culminating an endogenous process or as the effect of contact with France? . . . In sum, during the colonial period (1830–1962), the colonized society saw patrimony in economic terms: a building’s value was based on its materials (marble or volcanic tuff columns, marble or terra cotta tile floors, walls lime-washed or adorned with painted faïence tiles) and extended spaces, especially patios. From 1863 to 1896, colonial society considered that the only economic value of local heritage was in attracting tourists, even before the associations created by the first colonizers identified the Roman presence in North Africa with French colonialism and made it into another foundation of colonial memory.39

Ouagueni’s examination of France’s colonial-built heritage in Algeria is important for Oran and Sidi-Bel-Abbès, the focus of two chapters. With its majority European settler population, Oran’s center was long considered to have the longest continuous inhabitation of French and Spanish in Algeria.40 But because Oran had no ancient center or “primitive” Arab element, it was unfavorably compared during the colonial era with more picturesque walled cities such as Fez, Tlemcen, Rabat, Algiers, and Marrakesh known for labyrinthine streets and homes with interior patios invisible to outsiders.41 Although Algeria maintained French colonial heritage laws after independence, especially those that focused on precolonial architecture, until the 1999 revisions, these laws did not prevent changes, often seen as forms of decolonization, to war memorials and monuments in many Algerian cities and towns in the 1960s and ’70s. No one claimed them as Algerian heritage.

1. For the lyrics, music, and rise and fall of performances, see Le Chant des Africains, https://www.histoiredefrance-chansons.com/index.php?param1=MI0110.php.

2. Edward Gibbon, Memoirs of My Life (Hartnolls, UK: Ryburn Publications, [1796] 1994), 170. Quoted in Susan Stewart, The Ruins Lesson (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020), 20.

3. I borrow “monuments after all” from Georges Didi-Huberman’s title Images malgré tout (Paris: Minuit, 2003), on behalf of documenting the victim even through photography. His notion of survivance infuses my work to point to “the indestructibility of an imprint of time on our present life” alongside “the change of status, changing of meaning” (56, 59).

4. On French veteran commemorations, see Rémi Dalisson, En mémoire du 11 novembre: Vie et mort d’une fête nationale des origines à nos jours (Paris: Armand Colin, 2013); and Antoine Prost, Les anciens combattants (Paris: Gallimard, 1977).

5. The call for an anthropology of art for the MENA region is by Kirsten Scheid, “Start with Art: New Ways of Understanding the Political in the Middle East,” in Handbook for Political Science in the Middle East, ed. Larbi Sadki (New York: Routledge, 2022), 432–444. Social approaches about art were espoused by Clifford Geertz, “Art as a Cultural System,” Modern Language Notes 91 no. 6 (1976): 1473–1499. The role of colonialism in the creation of local art is beautifully analyzed in Hildred Geertz, The Life of a Balinese Temple: Artistry, Imagination, and History in a Peasant Village (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2004).

6. Eric Forcada, “Le monument de Sidi Ferruch d’Émile Gaudissard: Oeuvre de mémoires, mémoires d’une oeuvre (1830–2012),” Mirmanda: Revista de cultura 7 (2012): 78–88. A large scholarship exists on France’s “mission to civilize” in Algeria including Osama W. AbiMershed, Apostles of Modernity: Saint-Simonians and the Civilizing Mission in Algeria (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2010); and Alice L. Conklin, A Mission to Civilize: The Republican Idea of Empire in France and West Africa, 1895–1930 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997).

7. For witness testimony on the French army’s monument removal on July 5, 1962, see Jean Puissegur, “Mémorial Sidi Ferruch,” Commando Guillaume (blog), http://www.commandoguillaume.com/html/fra/page-42.html. For photographs of the Sidi-Ferruch monument and museum complex currently in France, see Fiona Barclay, “The Sidi-Ferruch Monument Revisited,” August 30, 2022, https://www.pieds-noirs.stir.ac.uk/sidi-ferruch-revisited/.

8. Jérôme Duhamel and Réné Pétillon, Grand inventaire du génie français en 365 objets (Paris: Albin Michel, 1992), 196: “Between 1919 and 1925, a war memorial was erected in every community in France, with one exception: the village of Thierville in the department of the Eure, the only French village which had no dead to mourn, either in 1870 or in [19]14–18, nor in [19]39–45.”

9. The literature is vast, but key texts recurring in this study are Maurice Agulhon, “La ‘statuomanie’ et l’histoire,” Ethnologie française, 8, no. 2/3, (1978): 145–172; and June Hargrove, The Statues of Paris: An Open-Air Pantheon (Paris: Vendôme Press, 1990). For French statuomania in Algeria, see Jan C. Jansen, Erobern und Erinnern. Symbolpolitik, öffentlicher Raum und französischer Kolonialismus in Algerien, 1830–1950 (Munich: Oldenbourg, 2013); and for postindependent Algerian statuomania, see Jan C. Jansen, “1880–1914; une statuomanie à l’algérienne,” in Histoire de l’Algérie à la période colonial: (1830—1962), ed. Abderrahmane Bouchène (Paris: Découverte, 2012), 261–265; Raphaëlle Branche, “The Martyr’s Torch: Memory and Power in Algeria,” Journal of North African Studies 16 (2011): 431–443; Emmanuel Alcaraz, Les lieux de mémoire de la guerre d’indépendance algérienne (Paris: Karthala, 2017); and Amar Mohand-Amer, “Les monuments aux martyrs en Algérie,” in Dictionnaire de la guerre d’Algérie, ed. Tramor Quemeneur, Ouanassa Siari-Tengour, and Sylvie Thénault, 831–832 (Paris: Éditions Bouquins, 2023).

10. Peter Edwards, “‘Mort pour la France’: Conflict and Commemoration in France after the First World War,” Journal of Contemporary History 1 (2000): 1–11: “The British ruled out repatriating their dead because of expense and prohibited individuals bringing bodies home for reasons of equality. The Americans had promised to bring home their dead if requested and 70 percent were repatriated. Conversely Germany was ‘in no position’ to exhume its dead from the areas it had occupied. However, the fact that the majority of the French dead had fallen on, and were buried in, their home soil raised other issues” (3). On names and absences, see Thomas W. Laqueur, The Work of the Dead: A Cultural History of Mortal Remains (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015), 417; Daniel J. Sherman, “Bodies and Names: The Emergence of Commemoration in Interwar France,” American Historical Review 103 (1998): 443–466; and Daniel J. Sherman, The Construction of Memory in Interwar France (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999).

11. In Cara A. Finnegan, Making Photography Matter: A Viewer’s History from the Civil War to the Great Depression (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2015), 131–132; she highlights viewer agency.

12. In Arthur Asseraf, Electric News in Colonial Algeria (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 41–42; he notes that the colonial surveillance system regulated publishers but not the viewing public. Nicholas Mirzoeff’s term is “visuality,” the sum of circulating images, or in this case French colonial ideas and information, against which he proposes a decolonial “right to look,” a crucial historical moment for Algeria’s production of monuments, see Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 1–34.

13. Throughout the text, I draw on scholarship by Antoine Prost, “The Algerian War in French Collective Memory,” in War and Remembrance in the Twentieth Century, ed. Jay Winter and Emmanuel Sivan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 161–176; Annette Becker, Les monuments aux morts: Patrimoine et mémoire de la Grande Guerre (Paris: Éditions Errance, 1988); and Henry Rousso, Face au passé: Essais sur la mémoire contemporaine (Paris: Éditions Belin, 2016).

14. For the English translation of the Évian Accords, see “Algeria: France-Algeria Independence Agreements (Evian agreements),” International Legal Materials 1, no. 2 (1962): 214–230.

15. Post–World War II Germany and France hosted respectively former German-speaking settlers from lost settlements in the east and European settlers of Algeria as repatriates (although France was less welcoming to the Muslim Harkis), and provided numerous and successive state-sponsored resettlement and reparation programs, see Jan C. Jansen and Manuel Borutta, Vertriebene and Pieds-Noirs in Postwar Germany and France: Comparative Perspectives (Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2016). On Diefenbacher and French reparations to the category of the repatriated, see Sung-Eun Choi, Decolonization and the French of Algeria: Bringing the Settler Colony Home (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 147–149.

16. Loi 61-1439 du 26 décembre 1961 relative à l’accueil et à la réinstallation des Français d’outre-mer (Law 61-1439 of December 26, 1961 on the reception and resettlement of overseas French) JORF, December 28, 1961, 11996: “Français ayant dû quitter ou estimé devoir quitter, par suite d’événements politiques, un territoire où ils étaient établis et qui était antérieurement placé sous la souveraineté, le protectorat ou la tutelle de la France”; and Michel Deifenbacher, Rapport Parachever l’effort de solidarité nationale envers les rapatriés: Promouvoir l’oeuvre collective de la France outre-mer (Paris: Documentation française, December 18, 2003). See the excellent discussion about terms for the French settlers of Algeria in Choi, Decolonization and the French of Algeria, 52–75.

17. See Susan Slyomovics, “‘False Friends?’: On Algeria, the Algerian Jewish Question, and Settler Colonial Studies,” in Race, Place, Trace: Essays in Honour of Patrick Wolfe, eds. Lorenzo Veracini and Susan Slyomovics (London: Verso, 2022), 58–89.

18. Anglophone scholarly literature (and of course the French language as an orthographic principle) do not capitalize, but English italicizes pied-noir. For definitions based on “pioneer,” see Pierre Bourdieu, The Algerians (Boston: Beacon Press, 1961), 130.

19. Benjamin Stora, “Pied noirs,” in Les mots de la colonisation, ed. Sophie Dulucq et al. (Toulouse: Presses universitaires du Mirail, 2008), 91.

20. Pierre Bourdieu, The Algerians, 152; and Susan Slyomovics, “French Restitution, German Compensation: Algerian Jews and Vichy’s Financial Legacy,” Journal of North African Studies 17, no. 5 (2012): 881–901.

21. The aforementioned Law of December 26, 1961, applied to European settlers (“repatriates”) holding French citizenship and returning from Algeria to France. Its purpose was to ease their economic and social integration into France, while a decree of March 10, 1962, set the conditions for allocating resettlement loans and grants. Neither law nor decree was applied to the Harkis.

22. Sung-Eun Choi, “The Muslim Veteran in Postcolonial France: The Politics of the Integration of Harkis after 1962,” French Politics, Culture, and Society 29, no. 1 (2011): 24–45. On the five military groupings of Harkis serving in the French military, see Abderrahman Moumen, Les Harkis (Paris: Éditions Le Cavalier Bleu, 2008).

23. Lorenzo Veracini, “Settler Collective, Founding Violence and Disavowal: The Settler Colonial Situation,” Journal of Intercultural Studies 29, no. 4 (2008): 363–379.

24. According to Andrea Smith, hundreds of thousands of Europeans, who arrived as settlers and colonists on North African shores as of the early nineteenth century, constituted an “invisible” migration; their decolonization became the story of an invisible return, of people coming “home” propelled by postindependence movements in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya, see Andrea L. Smith, “Introduction: Europe’s Invisible Migrants,” in Europe’s Invisible Migrants, ed. Andrea L Smith (Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam Press, 2003), 9.

25. Patrick Wolfe, “Recuperating Binarism: A Heretical Introduction,” Settler Colonial Studies 3, no. 3/4 (2013): 257. A double exposure and two images superimposed characterize nostalgia, according to Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic Books, 2002). On distinctions between colonial nostalgia (France) and imperial nostalgia (Britain), see Patricia M. E. Lorcin, “The Nostalgias for Empire,” History and Theory 57, no. 2 (2018): 269–285.

26. Andrea L. Smith, Colonial Memory and Postcolonial Europe: Maltese Settlers in Algeria and France (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006).

27. Alain Amato, Monuments en exil (Versailles: Éditions de Atlanthrope, 1979), 11–21. See SHD 1R 368. On archive removals, see Todd Shepard, “‘Of Sovereignty’: Disputed Archives, ‘Wholly Modern’ Archives, and the Post-Decolonization French and Algerian Republics, 1962–2012,” American Historical Review 120, no. 3 (2015): 869–883; and Susan Slyomovics, “Repairing Colonial Symmetry: Algerian Archive Restitution as Reparation for Crimes of Colonialism?” In Time for Reparations: A Global Perspective, ed. Jacqueline Bhabha, Margareta Matache, and Caroline Elkins (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021), 201–218.

28. The remarkable story of the return of French paintings to Algiers after their removal from the Algiers Musée National des Beaux Arts (National Museum of Fine Arts) at independence is described by former settlers Élisabeth Cazenave and Jean Christian Serna, Le patrimoine artistique français de l’Algérie: Les oeuvres du Musée nationale des Beaux-arts d’Alger de la constitution à la restitution (Chire-en-Montreuil, France: Éditions Abd-el-Tif, 2017), 26–47. Cazenave, an art historian, provides an inventory of the returned objects, deemed “repatriated” when returned to Algeria. See also Andrew Bellisari, “The Art of Decolonization: The Battle for Algeria’s French Art, 1962–70,” Journal of Contemporary History 52, no. 3 (2017): 625–645.

29. Conquest enforced by laws brought Algeria under various French civil and military authorities by the ordinance of July 22, 1834, which officially annexed Algeria’s Ottoman territories; the ordinance of March 4, 1848, which granted the northern provinces of Algiers, Constantine, and Oran departmental status; and the law of December 24, 1902, placed the Sahara (Southern Territories) under military administration.

30. On monuments, see Alois Riegl, “The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Its Origin,” Oppositions 25: (1982 [1903]): 20–51. For the notion of the ensemble, see Tilmann Breuer, “Ensemble: Konzeption und Problematik eines Begriffes des Bayrischen Denkmalschutzgesetzes,” Deutsche Kunst und Denkmalpflege 34 (1976): 21–38.

31. See English and French texts available at the Icomos site: https://www.icomos.org/en/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/167-the-athens-charter-for-the-restoration-of-historic-monuments.

32. Regina F. Bendix, Aditya Eggert, and Arnika Peselmann, Heritage Regimes and the State (Göttingen: Universitätsverlag Göttingen, 2012), 11.

33. Robert Shannan Peckham, “Introduction to the Politics of Heritage and Public Culture,” in Rethinking Heritage, Politics, and Culture in Europe, ed. Robert Shannan Peckham (London, I. B. Tauris 2003), 1.

34. Nasser Rabbat, “Identity, Modernity, and the Destruction of Heritage,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 49 (2017): 740. Although turāth often fills the slot of tangible architectural “heritage” in many contemporary preservation projects, the Arabic term extends to spiritual and textual Islamic culture, see Nabila Oulebsir, Les usages de patrimoine: Monuments, musées et politique coloniale en Algérie (1830–1930) (Paris: Édition de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, 2004), 14.

35. National Council of the Algerian Revolution (Conseil National de la Révolution Algérienne, CNRA), 1962, Tripoli Program, available at: http://www.el-mouradia.dz/francais/symbole/textes/tripoli.htm: “Sa prospérité économique, la vigueur exceptionnelle de son people, ses traditions de lutte, son appartenance à une culture et à une civilisation communes au Maghreb et au monde arabe, ce sont là autant de facteurs qui ont longtemps soutenu la résistance nationale. . . . . . La nécessité de créer une pensée politique et sociale nourrie de principes scientifiques et prémunie contre les habitudes d’esprit erronées, nous fait saisir l’importance d’une conception nouvelle de la culture. La culture algérienne sera nationale, révolutionnaire et scientifique. Son rôle de culture nationale consistera, en premier lieu, à rendre à la langue arabe, expression même des valeurs culturelles de notre pays, sa dignité et son efficacité en tant que langue de civilisation. Pour cela, elle s’appliquera à reconstituer à revaloriser et à faire connaître le patrimoine national et son double humanisme classique et moderne afin de les réintroduire dans la vie intellectuelle et l’éducation de la sensibilité populaire.”

36. Susan Slyomovics, “‘The Ethnologist-Spy Was Hanged, At That Time We Were a Little Savage’: Anthropology in Algeria with Habib Tengour.” Boundary 2o: An online journal 3 (2018), https://www.boundary2.org/2018/12/susan-slyomovics-the-ethnologist-spy-was-hanged-at-that-time-we-were-a-little-savage-anthropology-in-algeria-with-habib-tengour/.

37. Loi 98-04 du 20 Safar 1419 correspondant au 15 juin 1998 relative à la protection du patrimoine culturel (Law 98-04 of 20 Safar 1419 corresponding to June 15, 1998 on cultural heritage) JORA, June 17, 1998, 3–15.

38. Loi 99-07 du 19 Dhou El Hidja 1419 correspondant au 5 avril 1999 relative au moudjahid et au chahid (Law 99-07 of 19 Dhou El Hidja 1419 corresponding to April 5, 1999 on moudjahid and chahid), JORA, April 12, 1999, 3–9.

39. Yassine Ouagueni, “The Birth of the Notion of Patrimoine (through the Generations) in Algeria,” Journal of North African Studies 25, no. 5 (2020): 753–770; Nora Gueliane and Kaouther Bouchemal, “Algeria and Its Heritage: Inventory of the Various Heritage Policies, from the Pre-colonial to Colonial and Post-colonial Times,” in Transcultural Diplomacy and International Law in Heritage Conservation, ed. O. Niglio and E. Y. J. Lee, 257-272 (Springer: Singapore, 2021); and Nabila Oulebsir, Les usages de patrimoine.

40. Charles-André Julien, Histoire de l’Algérie contemporaine (Paris: PUF, 1979), 255.

41. The city plans of the Danger family of architects are cited in Jean-Pierre Frey, “Figures et plans d’Oran 1931–1936, ou les années de tous les Danger,” Insaniyat 23–24 (2004): 111–134.