“There is absolutely no difference from an economic perspective between bread kneaded and baked at home and bread kneaded and baked in the market.”1 Beiruti writer Julia Dimashqiyya (1882–1954) wrote these words in a front-page editorial in her journal, al-Marʾa al-Jadida (The New Woman), in 1924. In spirited, colloquial prose, she rejected the divide between the public and the domestic that made what women produced in the household less visible, and less valuable, than what men produced in the factory or the fields. “The sweat that pours from the virtuous woman’s brow as she irons clothes at home,” she declared, “is no less than the sweat for which we pay a high price at the laundry.”2 Dimashqiyya was a staunch supporter of women’s suffrage and their right to work in male-dominated professions when necessary. But in this editorial, she argued that not all calls for women’s rights required making new demands or entering spaces occupied by men. Instead, the path to broader rights for women required convincing her audience that work done in the home had equal value to work done outside of it. “The most important right that has been stolen from us [women],” she wrote, “is knowing the value of women’s labor at home.”3 Before all else, women needed to make men see that “that women’s keeping of the house is not less than men’s keeping of the office” and “that the rearing of children [tarbiyat al-awlād] is more valuable, and more arduous, than any work performed by men.”4

Dimasqhiyya’s 1924 editorial identified home and family as spaces of labor comparable—but not identical—to the spaces of labor occupied by men. She addressed concerns that were, or would become, important for feminists globally over the course of the twentieth century: the place of women’s work, the pathways to women’s political rights, and the emergence of different spheres of action for women and for men.5 At the same time, Dimashqiyya made a curious suggestion. Respect for the work of washing clothes, baking bread, and rearing children was somehow intertwined with women’s demands for voting and political participation. What did women’s kneading hands, tender hearts, and sweating foreheads have to do with their calls for equal citizenship and equal rights? What was the relationship between gendered forms of reproductive labor and the stubborn exclusion of women from liberal political regimes?

This book explores these questions by turning to the work Dimashqiyya judged most valuable and difficult: the rearing of children, or in Arabic, tarbiya. Reconstructing theories of motherhood and childrearing in the Arabic press reveals how women’s embodied and affective labor became foundational to modern life in ways that capitalism, nationalism, and liberalism have long attempted to obscure. In the pages that follow, we see how writers working in Arabic made a seemingly timeless human practice—the raising of children—into a lynchpin for representative politics, progress and development, and social order. At the same time, they insisted that childrearing was women’s unpaid work.

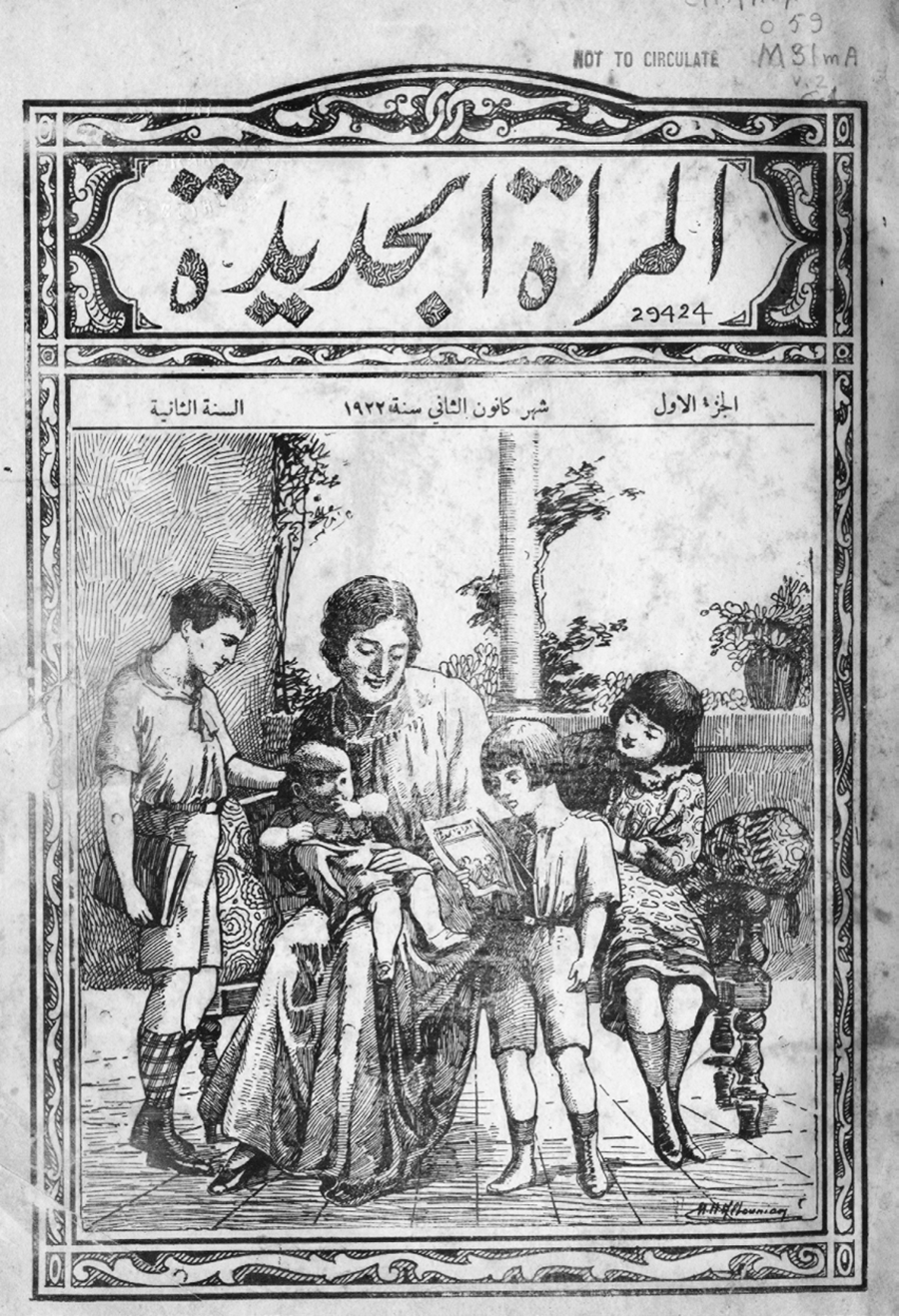

While elements of Dimashqiyya’s arguments were novel, the idea of a woman writing in the Arabic press was not. Women had been contributing to journals published in places like Cairo and Beirut since the 1850s.6 By the 1890s, women were founding and editing journals themselves. Far from silent, secluded creatures barred from public life, women writers working in Arabic were outspoken, active, and deeply engaged in the world around them through the pages of the press. While some women’s journals were ephemeral, lasting only a couple of years, others lasted for decades, bringing readers and writers together in an expansive print community that spanned the Arab East, or the Mashriq (what is now Syria, Israel/Palestine, Iraq, Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon), and its diasporas.7 The urban areas of the Arab East, especially the culturally connected cities of Beirut and Cairo, became the region’s publishing centers. The women’s journals published in these cities fanned out to reach a small but growing population of literate readers drawn from the elite and rising middle classes. They were also shared, discussed, and read aloud, reaching audiences beyond their formal readerships. The journals mostly featured women writers, occasionally joined by male colleagues; covered issues like women’s rights, social roles, and education; and included biographies (often of women), serialized fiction, songs, poetry, and general news and social commentary. In addition to the coffeehouses, presses, and schoolrooms often considered central to Arab intellectual life at the turn of the twentieth century, women’s journals were also meant to be read at home, with children on the knee. A 1922 cover of Julia Dimashqiyya’s al-Marʾa al-Jadida (fig. 1) depicts a woman reading the journal to her children, gathered around her.

The rise of the Arabic women’s press was part of the era of the nahḍa, a period of cultural renaissance in the Arab East between 1850 and 1939 that emerged from the uneven expansion of capitalism, European encounter, and Ottoman state-building and reform. The cities at the center of our story, Beirut and Cairo, began this period as provincial capitals within an Ottoman imperial framework, subject to the Sultans who had ruled in Arab lands since the sixteenth century. In the nineteenth century, both cities became integrated into a capitalist world economy and the tightening net of European colonial expansion. Egypt was occupied by the British in 1882, and the region of Greater Syria (now Syria, Israel/Palestine, Jordan, and Lebanon) became subject to increasing European missionary and colonial attention. After World War I, the defeated Ottoman Empire ceased to exist, replaced by the Republic of Turkey and modern Arab nation-states under varying degrees of semicolonial control by European powers. By the early 1920s, Beirut and Cairo were capitals of the states of Lebanon and Egypt. Despite this tumultuous and increasingly divergent political history, middle-class intellectuals and their work continued to circulate between Cairo and Beirut throughout the interwar period; a regional print culture knit the Arab East together despite new political boundaries.8 The story of the nahḍa, and of the roles women, gender, and sex played within it, thus requires bringing the histories and historiographies of Egypt and Lebanon together, highlighting the connections between them as well as their specificities.

The women and men who lived in Cairo and Beirut between 1850 and 1939 turned to tarbiya to address three central challenges that defined their age. First was the emergence of capitalist society and the rise of a powerful middle class of bureaucrats and intellectuals who dreamed of limited, gradual reform while struggling to maintain existing hierarchies based on class, age, and gender. Second was the emergence of movements seeking to replace an older politics of sultanic authority and hierarchical interdependence with popular sovereignty and representative democracy, a project complicated by the ongoing advances of European empires. Third was the slow and incomplete suppression of the trade in enslaved people and the rise of a heterosexual, nuclear family ideal that redistributed domestic work in elite and middle-class households in unprecedented ways. Writers in the Arab East identified the feminized work of childrearing—that is, the work of childrearing assigned to women—as a way to guide and control these transformations. As they debated what it meant to bear and raise a child, writers tasked women with a doubled form of labor: they tied social reproduction, or the reproduction of labor under capitalism, to political reproduction, or the reproduction of citizens for self-rule.

Labors of Love tells the story of women’s reproductive work and modern social thought through a history of the concept of tarbiya, an Arabic word for the general cultivation of living things that came, over the course of the nineteenth century, to refer primarily to women’s childrearing labor in the home. Between the 1850s and the 1930s, upbringing (tarbiya) and formal education (taʿlīm) became central subjects of concern among literate people in the Arab East. Missionaries, Ottoman statesmen, and members of the region’s own elite and middle classes entered into fierce competition over the domain of education. Eager to poach one another’s students, they read each other’s books and journals and founded schools side by side. They were especially interested in educating girls as “mothers of the future,” practitioners of tarbiya who could advance particular agendas by instilling proper principles in young children in the home. This attitude of competition led to substantial cross-pollination. Across sect, gender, and geography, writers debated how to feed a newborn, whether to swaddle, and how to inspire obedience and respect. What constituted good tarbiya, they wondered, and what could it accomplish? Together, they turned to tarbiya to face a challenge that has troubled modern societies around the globe: how to reproduce bodies for labor, citizens for self-government, and subjects for a social order capable of both stability and progress. In so doing, they turned women’s childrearing work into a form of world-making that did not require power over the pedagogical or disciplinary apparatus of the state.

If the communities of readers and writers who argued about how to raise a child between 1850 and 1939 were diverse in terms of geography, sect, and political belonging, they generally occupied similar social positions. Most theorists of tarbiya enjoyed relative privilege and cultural authority, because they had the education, time, and resources to participate in the world of publication. Publishing and education were essential to forging a new class of intellectuals, a culturally powerful subset of an emerging middle class, distinct from the landed elites and rural cultivators who had dominated the region’s population until the nineteenth century.9 Incorporation into a global capitalist economy from mid-century onward pushed many off their land while also bringing new opportunities for urban professional employment. These new pathways enabled the rise of a new middle class. Tarbiya, in turn, came to express a bourgeois sensibility: it spoke to concerns about progress, sex, and social order that became dear to middle-class women and men across a multiconfessional religious landscape. Ideas about upbringing made their way into law, public policy, school curricula, and libraries, shaping the gendered boundaries of modern political life.10 But concepts like tarbiya should not be read only as vehicles for expressing particular class interests.11 This book argues that tarbiya also captured and responded to essential political questions presented by the era’s historical transitions. Its theorists had a great deal to say about the changes they wrought and witnessed. This history of their concept is my attempt to listen.

The argument of this study takes shape on two levels.12 On one level, it is a conceptual history of tarbiya in Arabic thought and letters between 1850 and 1939, focusing on the Arabic women’s press. It asks why people talked and wrote so much about how to raise a child, and how their ideas about childrearing and motherhood shaped how they thought about politics, society, gender, and colonialism, and vice versa. As such, the book argues that both women writers and questions of gender and sex have been central to the development of Arab intellectual and political life beyond the confines of well-known debates about the status and rights of women. Specifically, it shows how a broad faith in middle-class women’s power as childrearers enabled Islamists, liberals, and feminists alike to contend with three questions that defined intellectual life: how to imagine futures after imperial rule, how to balance the promises of democratic politics with the interests of reformist elites, and how to stabilize existing social hierarchies under the shifting conditions of colonial capitalism. In other words, the story of tarbiya lays out some of the central contradictions of democracy and capitalism as they were encountered in Cairo and Beirut.

On another level, the book attempts to think with the concept of tarbiya to analyze the broader questions of social and political reproduction that challenged Arab intellectuals and many others at the turn of the twentieth century, and that continue to challenge us today.13 It shows how writers, both men and women, turned to childrearing to understand and shape the changes happening around them. These writers insisted that reproduction was not a “hidden abode” but a central domain of world-making and therefore of political contestation.14 This domain has gone unexplored by scholars who have seen political theory as something done by men in the public sphere. But theorists of tarbiya, many of whom were women, made a key contribution to understanding politics and social life by tying together two domains usually kept separate. The first was social reproduction, the task of raising children and keeping adults fed, clothed, and socialized to be healthy and productive members of a laboring society. The second was political reproduction, the task of creating moral, governable, and trustworthy subjects for representative self-government. By positioning both of these domains as women’s work, writers feminized a contradiction essential to capitalist society and liberal political regimes: dependence on nominally free and self-owning adult actors who have, in fact, already been shaped outside of the formal spaces of politics and economic exchange. In other words, tarbiya turned the contradictory task of shaping subjects to be free and self-owning into women’s work.

Theorist Nancy Fraser has argued that capitalism depends on “background conditions of possibility,” notably the reproduction, often assigned to women, of the people whose work sustains wage labor and capital accumulation.15 The story of tarbiya illustrates that democracy has also relied on such background conditions: it presumes citizens who have already been shaped to make them trustworthy enough to administer the state. In the Arabic-speaking world, as in many places, that work has also been assigned to women in the home. The story of tarbiya shows, then, that the long-standing focus on motherhood in Arab thought not only sidelined women from formal political life. It also asserted the centrality of women’s childrearing to the formation of political and laboring subjects, and thus to addressing the broader challenges of democracy, capitalism, and popular sovereignty in the modern world.

As the twentieth century wore on, feminist movements in the Arab region and around the world would turn their attention to women’s waged work and political and legal equality. Earlier visions, however, have had multiple afterlives. While the world changed in ways that theorists of motherhood and domesticity did not foresee, their ideas continue to shape what it means to work, to participate in politics, and to live together. By highlighting the importance of tarbiya, writers insisted on both feminizing and emphasizing the question of political and social reproduction. Their focus on women’s sweat, foreheads, and hearts, and on the embodied labor of mothering and childrearing, offers a new angle of vision on histories of women, gender, and feminism, as well as of Arab intellectual life. More broadly, their work offers new ways to think about the emancipatory promises and drastic limits of capitalist social relations and representative self-government in the Arabic-speaking world and beyond.

This book argues that the concepts we use to write history can be forged in Beirut and Cairo as well as in London or Berlin. Concepts are abstract tools that shape how we understand both the past and the present. They create networks of meaning that make it easy to get from some places to others, for example from freedom to independence, while rendering other pathways, like the one connecting women to politics, harder to follow. Too often, the concepts that travel across multiple contexts to enable writing and thinking in the social sciences—concepts like class, gender, or even work itself—are drawn from European and American histories, which fill them with specific meaning. We know what work is, for example, because we know what it looked like in a textile factory in Manchester, or because we read Karl Marx on man transforming nature.16 We learn what freedom is through the US Declaration of Independence or the works of French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. This book argues that a practice of history writing that extends beyond the Euro-American world needs a wider array of conceptual tools, forged out of different pasts and in light of different presents. Concepts help us to understand and shape the world, and when the grounds for concept-building change, so too do the questions we ask and the conclusions we draw.

This book turns to the social history of Arabic thought to introduce tarbiya as an analytic concept—alongside class, gender, or labor—for the writing of history in and beyond the Arabic-speaking world. The story of tarbiya brings to light essential questions that stretch far beyond the Arab region: when and where has childrearing been made into women’s work? When and where have women been tasked with resolving the tensions of collective existence, and to what effects? In other words, what would a history of tarbiya reveal in Mexico, China, or the United States?

Approaching the problem of Eurocentric categories in this way offers an alternative to what historian Dipesh Chakrabarty famously named “provincializing Europe.” Chakrabarty argued for renewing the body of European social thought that traveled around the world on the wings of capitalism and imperialism “from and for the margins.”17 He asked what happened when that body of thought confronted lifeworlds and categories in the Global South that could not be easily assimilated to its terms. This study works, by contrast, not to provincialize Europe but to globalize the Arabic-speaking Middle East: to portray it as a region generative of concepts and theories that not only illuminate its own past but help us to understand capitalism, society, and democracy elsewhere.18 Adopting tarbiya as an analytical concept encourages scholars to attend to how conceptions of childrearing, gender, and reproductive labor have deeply shaped political and social life. This book thus reads Arabic thought not as a repository of cultural difference but as diagnostic of the world.19 Tarbiya responded to questions that troubled people in many places at the turn of the twentieth century and that are still very much with us in the present: how do we account for the labor of rearing not just bodies for work but subjects for democratic politics and collective life? As the feminized work of childrearing and education goes un- or underpaid and unrecognized as a cornerstone of how we live together, these are conundrums we still face. This means that there is much to learn from a time and place when writers forced the politics of care and the problems of reproduction to the heart of political and social thought.

Tarbiya was both a specific cultural formation and one embedded in the global and transregional contexts in which it emerged. The concept took shape in a multilingual, multiconfessional region that had been deeply entangled with other parts of the world for many centuries. While Sunni Muslims were the dominant confessional group in the late Ottoman Empire, the Arab East was also home to various Christian sects and long-standing Jewish communities, as well as other faiths. And while Arabic was the language of Islam and Ottoman Turkish, the language of the Empire’s upper bureaucracy, people in the region spoke many different Arabic dialects, as well as languages like Syriac, Ladino, Armenian, and Greek. With the growth of the press in the nineteenth century, Arabic became a shared language among the region’s educated class. But publications also emerged in other regional languages, and conversations about women’s childrearing work—about tarbiya—appeared in Armenian, Greek, and Ottoman Turkish as well.

Women like Julia Dimashiqyya played a central role in the tarbiya debates in the Arabic-speaking world. The questions Dimashqiyya raised were shared by women whose life stories and even names are unknown, as well as by more recognizable figures like Cairo-based Islamist feminist Labiba Ahmad (ca.1870–1951), Beirut-based Protestant ethicist and lecturer Hana Kasbani Kurani (1871–1891), and Labiba Hashim (1882–1952), the Beirut-born editor of Cairo’s longest-running women’s journal, Fatat al-Sharq (Young Woman of the East). These women and other theorists of tarbiya joined multiple circuits of reading, writing, and translation that connected the pedagogues of the past to the present. They invoked a vast web of interlocutors, ranging from eighteenth-century philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Johann Pestalozzi to luminaries from the Islamic tradition such as philosophers al-Ghazali and Miskawayh.20 Their eclectic references put the radical utopianism of revolutionary France in conversation with Protestant New England’s austere evangelism, the love and shame of Catholic devotion, and the balance and moderation commanded by Islamic virtue ethics, or akhlāq.

Theorists of tarbiya worked across not only time but space, joining a boom in pedagogical thinking and educational expansion that stretched from Boston to Beijing. During this nineteenth-century “age of education,” people around the world looked to childrearing and schooling to forge national and imperial collectives, improve industrial and military outcomes, and control social unrest.21 In previous eras, education had largely been the purview of local communities, religious organizations, or families, but around the nineteenth-century world it increasingly became a domain of imperial and later national importance. Given the broader global moment, it is no surprise that writing on tarbiya sometimes brings to mind notions of Republican motherhood, Victorian womanhood, and the “cult of the mother” that took shape in England, France, and the United States.22 Tarbiya also resonated with concepts taking new forms in other languages. One example is the English culture, through which writers grappled with the emergence of capitalist society, confronted the destabilizing potential of democratic politics, and strove to create an extra-political and extra-economic space to be represented and adjudicated by the state.23 Another example is civilization, through which people thought about the kinds of self-discipline required to manage interdependent and highly differentiated societies, or the German bildung, which came in the nineteenth century to emphasize autonomous self-formation and people’s abilities to transform the world around them.24

Theorists of tarbiya working in Arabic were certainly aware of contemporary discussions happening in English, German, and French, and they engaged and translated pedagogical works published in Europe. This book, however, does not tell the story of tarbiya primarily as one of the transmission or translation of ideas and questions that had their first articulations elsewhere.25 Instead, it asks why the concept of tarbiya became so durable and powerful in the Arabic-speaking world. What conditions made people so interested in how to raise a child? What questions did the concept answer, and what did it make possible to think and do? I suggest, in other words, that the history of concepts like tarbiya should be analyzed “in terms of the practical structures that render that concept a compelling lens through which to make sense of the world.”26 Put differently, what was happening in people’s everyday lives and social worlds that made a certain concept speak so vividly to their experiences? In light of tarbiya’s resonances in other places, we must consider that some of those “practical structures” extended beyond the boundaries of the Arab East. We will see how people invested in tarbiya in light of questions that came to seem urgent in the region and elsewhere around the world.27

The rest of this book focuses on three questions that drove people to think and talk so much about what it meant to raise a child, each of which reverberated both within and beyond Cairo and Beirut. The first question, treated in chapters 1 and 5, was about how to understand change over time in an era of missionary evangelism, state-building, and colonial expansion. Between 1850 and 1939, writers working in Arabic turned to tarbiya to engage the idea that change over time was a matter of steady progression along a universal, linear path, a process many called progress (taqaddum) or civilization (tamaddun). As critics both at the time and since have recognized, this temporality had a politics: it placed some people ahead and others behind.28 Such questions had special significance during the colonial period, since colonial administrators often justified their empires’ expansions by claiming they were more civilized and developed than the inhabitants of the lands they ruled. In this context, the politics of linear time presented writers working in Arabic with an urgent question: if all societies were advancing along a unified path, wouldn’t Europe always be “ahead” and the Arab world “behind”? How could linear time allow for either “catching up” to Europe or opening a future that didn’t follow European example?

In light of this conundrum, writers turned to tarbiya to reframe how time worked. Some argued for childrearing as a temporal model for collective development, naturalizing an understanding of political change as gradual, top down, and subject to prediction and control. These writers maintained that societies, like children, would move—with proper tutelage—from child to adult forms along prescribed and gendered paths, albeit guided by local reformers rather than European officers or missionaries. Other writers turned to the mysteries of the child and adolescent body to rupture the linear time of progress and civilization and to open up possibilities for new, revolutionary beginnings.

The second question that tarbiya came to answer for Arab thinkers was that of the social: how to think about collective life in an era of profound transformation. This question drives the narrative in chapters 2 and 3. Between 1850 and 1939, the integration of the Arab East into a capitalist world economy brought people who would never meet together through new networks of production, consumption, debt, and exchange.29 A peasant laboring on a cotton estate in the Nile Delta became linked to a London banker who had speculated on the cotton harvest; a textile producer in Beirut could have the price of their product undercut by fabrics brought in from India or Japan.

These newly abstract forms of interdependence made way for middle-class writers to produce an equally abstract concept of society through which they could apprehend and shape the new dynamics of collective life. That concept would help to stabilize existing hierarchies in the face of colonialism and capitalism, which transformed how land was owned and worked, how goods were traded, and how people managed to survive. Meanwhile, the spread of print media and modern education cohered a new class of literate intellectuals—journalists, writers, educators, and reformist bureaucrats—whose members felt distinct from, and often threatened by, the masses of working people and peasants who lived alongside them.30 These fears, broadly shared among the region’s elite and emerging middle classes, became acute as peasants rose up against landholders, for example in the rural districts of Mount Lebanon north of Beirut in 1858–60 and in Upper Egypt against the ruling Turco-Circassian elite across the 1800s.31 Throughout the region, working and rural people also engaged in other forms of social contestation, such as petitioning, banditry, land abandonment, and, by the 1890s, work stoppages and strikes.32

In light of these challenges, literate members of the elite and middle classes began to describe collective life through social theory, a new genre of writing that revolved around abstract concepts like “society” (al-mujtamaʿ) and “the social form” (al-hayʾa al-ijtimāʿiyya). Through descriptions of society, the rules it followed, and how it changed over time, they hoped to establish new norms for managing collective life. In their writings on the social, members of the middle classes also sought to distinguish themselves from both elites and working people and to forge the masses into an “organized and disciplined whole” that they could oversee, predict, and control.33 They attempted to naturalize ideas that states should be legitimated through limited popular representation, that nuclear families were best, and that men’s labor should be bought and sold as a commodity, while women’s work remained unpaid. By the 1890s, “the social” and “the social form” had become inescapable concepts in Arab intellectual life.34 Writers identified the work of childrearing and moral cultivation as essential to a healthy, coherent social whole. Through debates about tarbiya, they assigned that work to middle-class women working for free within the home. In so doing, they wove gender, sex, and class into the very foundations of modern social theory and political culture. This argument had real effects on women’s lives. Middle-class women gained access to new realms of education and authority, but they also became objects of men’s surveillance and control. Working-class and peasant women who could not afford to engage in full-time, unpaid domestic labor, in turn, became seen as dangers to the social whole and as objects of urgent reform.

The third question writers turned to tarbiya to answer, and the focus of chapters 4 and 6, was about how an older politics of sultanic authority and hierarchical interdependence under Ottoman rule gave way to struggles for popular sovereignty and representative democracy—what Cairo-based writer Rashid Rida (1865–1935) would call in 1909 “the rule of the community, by the community.”35 Prior to this period, the rule of the Ottoman sultans had been largely autocratic, with power emanating from Istanbul and working unevenly through networks of local and regional authorities, including landed families, tribal and religious leaders, and circulating bureaucrats appointed by the palace. Starting in the nineteenth century, the Ottoman Empire began to renegotiate its relationship to those it governed, opening up limited avenues for elite consultation.36 Under pressure from expanding European empires, Ottoman leaders began to centralize army and state and to move from autocratic governance through local proxies to increasingly consultative rule. By the 1860s, some Ottoman reformers had begun to support more decentralized governance, which lead to the promulgation of the first Ottoman constitution in 1876. The constitution, which was suspended in 1878, stipulated that people from around the Empire would elect deputies to an Ottoman Parliament. That document and its promises would be revived in a second Ottoman Constitutional Revolution in 1908. The promises of political participation and popular sovereignty the constitution made, however, were by no means populist in either intent or effect. Rather, these promises were fundamentally shaped by elites’ and reformers’ fears that people unlike them—in class, gender, or background—would use the document to claim political power for themselves. In response to those fears, the constitution and accompanying electoral laws worked to limit, channel, and constrain the votes of peasants and working-class people. The constitution also excluded women from voting or running for office.

As hopes and fears about constitutionalism and popular sovereignty rose to the fore in the Ottoman world, writers in Cairo and Beirut turned to tarbiya to ground new theories of politics, exclusion, and human subjectivity. They tasked women with raising male children who could be trusted with self-government, that is, who would consult and vote without contesting established forms of social hierarchy or the representative and educative power of reformist elites. At the same time, paradoxically, writers invested women’s childrearing labor with the power to raise men whose autonomous choices would legitimate the state. Tarbiya thus proposed a form of social theory that both enabled and precluded the autonomous male individual as the subject of politics. It located the work of shaping that individual male subject outside of the purview of the state and the market by identifying it as the work of women in the home. In the Arab East, then, thinking abstractly about society, governance, and democracy always required thinking through women’s labor and gendered bodies; what was happening in the public sphere always relied on what was happening at home.

The questions about change over time, social order, and popular sovereignty that preoccupied Arab intellectuals between 1850 and 1939 were not unique to the Arab world. The language of progress and development was on the rise across the Ottoman Empire and the French and British colonial empires.37 Questions of social life and social theory were ascendant in India, China, and Japan as well as Britain and France.38 And from Russia (1905–6) to Iran (1906) to Mexico (1910–20) to China (1911), other polities were turning to constitutionalism and representation in the context of revolution. Spirited conversations about motherhood, infant life, and childrearing likewise drove debate in many of those places.39 Thinking through the concept of tarbiya as social theory illuminates how and when people called on women’s bodies, hearts, and labor to resolve the challenges of reproduction that define modern social life. The story of tarbiya thus offers an occasion to redefine the supposedly European parameters of modern social thought. Rather than unmasking supposedly universal ideas like society or freedom as particular to Europe, it instead challenges the often implicit assumption that the domain of that which travels as theory is “European property” at all.40 People in many locations have turned to abstract concepts like tarbiya, theorized from within their particular contexts, to make sense of the many-layered worlds they inhabit. But tarbiya brings to light questions about gender and reproduction that are essential to understanding politics and society in the modern age. Tarbiya invites us to explore how childrearing may not only exclude women from formal political life but also make their work essential to its functioning.

As theory, then, tarbiya should be precisely that which travels: an idea, to borrow from Edward Said, that “gains currency because it is clearly effective and powerful” beyond the conditions it was originally forged to describe. Because theory travels, however, it also risks becoming overly general, failing to capture differences and specificity. As Said put it, theory can be “reduced, codified, and institutionalized . . . if a theory can move down, so to speak, to become a dogmatic reduction of its original version, it can also move up into a sort of bad infinity,” becoming a totality from which it is difficult to escape.41 The idea, then, is not to have better theory or more authentic theory but to keep theory in the plural and on the move. As Said argued, we must translate, borrow, and appropriate if we are “to elude the constraints of our immediate intellectual environment. . . . What is critical consciousness,” he asked, “if not an unstoppable predilection for alternatives?” Tarbiya is just such an alternative: a concept that can change what it has been possible to think, see, and do.42

I began the research that became this book wondering what the history of modern Arabic thought would look like viewed from the perspective of the women’s press and women writers. Between the 1880s and 1919, over thirty journals edited by women appeared in Arabic, many of them published in Cairo and Beirut. More yet would emerge between 1920 and 1939.43 Many had devoted and far-flung readerships, with some commanding audiences in the thousands.44 While women’s literacy rates expanded between 1880 and 1939, the conversations that circulated in journals probably reached audiences far larger than official rates suggest.45 What themes, questions, and concepts would come to light if we began from this world of women readers and writers rather than asking how women fit, or didn’t, into histories of Arabic thought that revolve around the work and worlds of men?46 This question seemed particularly salient for the period 1850 to 1939, in which binary categories of man and woman increasingly shaped how people understood the world.47 Men played an important part in the tarbiya debates, as we will see. But it was through a close reading of the women’s press that I first realized how important tarbiya was to the history of Arabic thought, and the story that follows keeps that archive at its center.

I use the binary categories of man and woman in my analysis because these categories structured how most writers working in Arabic thought about gender and sex between 1850 and 1939. My usage is not meant as an endorsement: on the contrary, part of what this book seeks to understand is how a binary gender regime, rooted in apparent social and physiological differences, became so powerful and durable. I also trace how gender and class—two essential categories of social difference—constituted one another, becoming more powerful together than they would have been apart. The book thus addresses gender as “a social category imposed on a sexed body” and uses it as a lens to understand the history of political and social thought.48 Following feminist biologists, however, I do not want to reify a strict boundary between “gender” (the social) and “sex” (the physiological).49 In fact, one of the things the story of tarbiya reveals is how much our understandings of physiological sex difference are shaped and influenced by ideas about gender. The line between the hard truth of the body and the cultural work of society is blurry and constantly changing, so histories of sex and gender must be told together.

There is no question that the category of “woman” shaped how writers operated in Cairo and Beirut between 1850 and 1939. One challenge of framing the story of tarbiya around women’s work is that women were less likely to become well-known intellectuals whose legacies would be documented and archived by later generations.50 Instead, early Arab women’s writing often appeared in short articles scattered throughout the vast, and largely uncatalogued, terrain of the early twentieth-century Arabic press. The appropriateness of women’s public writing was a hotly debated issue, and women writers were more likely than men to use pseudonyms or not to sign their work with their full name.51 Many of those who did sign are still barely visible within the historical record—their lives, inner worlds, and intellectual and political trajectories neither recorded nor preserved.52 This book turns to concept history to work with, rather than against, these characteristics of women’s writing. It traces how tarbiya took form through not just the singular insights of individuals but a recursive and entangled world of editorials, essay contests, and unsigned advice columns: the “thick underbrush” of Arabic thought.53

Labors of Love proposes feminist concept history as a method for the study of Arab intellectual life. Instead of looking for individual figures and their personal or political agendas, this book charts how writers in the women’s press used discussions of tarbiya to produce a powerful and gendered way of understanding the world. In so doing, they layered together the multiple meanings and rich contexts that the term was used to describe. The word thus became a concept: an index of, and a participant in, multiscalar processes of historical change.

The key premise of concept history as I understand it in this book is that concepts do not simply reflect changes taking place outside of language but sometimes actually help to bring those changes about. They are sites where social history and theory-making repeatedly collide. It is useful to think with Peter de Bolla about the construction of an “architecture” of concepts, as if concepts were like subway tunnels: mental infrastructure that makes it easy and natural to go from some locations to others, for example, from equality to representation, and difficult and counterintuitive to traverse other trajectories, for example from dictatorship to liberation, or, as we will see, from women to the vote.54 As I have argued, the fact that some pathways are easy and others difficult shapes not only how people think but what they can argue for and how they act.

In what follows, I track tarbiya’s plural, layered meanings while suggesting how these meanings were linked to broader processes of social, political, and economic change. Practically speaking, this meant combing libraries and archives in Lebanon, Turkey, Egypt, France, Britain, and the United States for the Arabic-language journals, especially those written or edited by women, across whose pages the concept of tarbiya took shape. It meant reading at a distance and then closely and repeatedly to identify key debates, moments, and inflection points in these diffuse and long-running discussions, focusing on not only writers’ political identities or personal trajectories (when evidence allowed) but also the way their comments about childrearing intervened in broader conversations. And it meant engaging in the more speculative work of thinking about how other people’s ideas and concepts—the ways they made sense of their worlds—both reflected and influenced historical change.

To adopt concept history as a feminist method is to recognize that knowledge production, as writers in the women’s press well knew, was collective, diffuse, and fundamentally shared. As speakers of particular languages who are embedded in communities of life, text, and practice, we are all working within a conceptual architecture that has been and continues to be forged with others and by forces beyond our direct experience or control. Individuals, in turn, do not make their own concepts. “There are no new ideas still waiting in the wings to save us as women, as human,” Audre Lorde reminds us. “There are only old and forgotten ones, new combinations, extrapolations and recognitions from within ourselves, along with the renewed courage to try them out.”55 This book turns to a concept forged in Arabic, often by and for women, as a place to look for and renew that courage.

The concept of tarbiya took shape alongside discussions of “the woman question,” the broad debates about women’s rights, education, and status in society.56 The woman question provoked considerable attention not only among women but among men, most famously Egyptian judge Qasim Amin (1863–1908).57 While Amin was once known as the “father of Egyptian feminism,” scholars have since demonstrated that women writers preceded him and sometimes offered more radical claims about women and their social roles.58 As these writers and many scholars since have recognized, the “woman question” was never just about women. It was also about how people in the Arab East would engage imperialism and commodity capitalism, forge a stable and progressive society, and eventually constitute an independent nation.59 Prominent women writers like Zaynab Fawwaz (1860–1914) and Mayy Ziyada (1886–1941) made the case that rethinking gender would be essential to rethinking politics, selfhood, and the state.60 Their conversations, in turn, laid the groundwork for feminist movements to emerge in the region in the first decades of the twentieth century.

Historians have explored the dimensions of Arab women’s intellectual production that can still be recognized as feminist—that is, their critiques and interventions about women’s roles in society, written with an eye toward change.61 Marilyn Booth’s luminous work on nineteenth-century writer and biographer Zaynab Fawwaz, for example, demonstrates how Fawwaz engaged in “feminist thinking” by critiquing structures of gender hierarchy and rejecting “institutionalized masculine authority over women and girls.”62 By highlighting the stories of exemplary and unusual women who challenged patriarchal social norms, these studies unmask those norms as “instruments of power” rather than reflections of nature, and they locate feminist role models for later generations.63 This work is particularly important for the Arabic-speaking world, which was once considered—and still is, by some—the location of particularly pernicious forms of patriarchy, a domain of silent, oppressed women in need of “saving” by the West.64 Histories of Arab feminism have demonstrated, by contrast, that patriarchy has always been as internally contested in the Arab world as elsewhere and that Arab women have always been well able to theorize their own social conditions, imagine other futures, and advocate for change.

The history of feminist writers and activism, however, is only one way to write feminist history.65 This book pursues a different approach, albeit one still driven by a feminist ethos. It turns to the history of Arabic thought to explain why the idea of embodied, binary gender difference as a natural foundation for human society has proven so difficult to overcome. I show how tarbiya forged categories of man and woman defined by particular reproductive capabilities. These binary categories, in turn, structured how people thought about state formation, anticolonial resistance, and democratic becoming. As binary gender became foundational to these essential questions in modern political and social theory, it began to appear natural, timeless, and impossible to change.

The pages that follow explore a body of thought that may appear regressive to contemporary feminist readers. Many of the writers we will meet valorized motherhood, femininity, and complementarity and grounded all three in unique capacities that they attributed to the female body. They thus helped to construct a binary and biologically justified gender regime and an exclusive and disciplinary form of middle-class reproductive heterosexuality. To seek to understand a way of thinking, however, is not to endorse it. We should not shy away from historicizing worldviews that we find politically unpalatable, especially when those worldviews—like the one that cohered around tarbiya—became enormously compelling, powerful, and successful in their own time and shaped the worlds in which we live today.

The theorists of tarbiya who are the focus of this work were not always unusual, challenging, rebellious subjects who strove to transform gender hierarchies and patriarchal structures. Many of these women and men worked instead—at least at times—to construct, maintain, and defend a social order marked by naturalized differences of gender, age, and class. If Zaynab Fawwaz and other Arab feminists sought to challenge “gender difference as a distributor of hierarchy and subordination,” as Marilyn Booth has argued, theorists of tarbiya were often more interested in highlighting the importance—indeed, the centrality—of binary gender difference and feminized labor to the success of civilization and progress, representative politics, and capitalist society.66 Their insistence on the importance of women’s reproductive work highlighted internal contradictions within liberalism and capitalism without taking aim at gender difference itself. Specifically, they argued that the free, self-owning adult subject who was expected to advance progressive reform, participate in representative politics, and freely sell his labor for a wage was in fact not autonomous at all: he was a direct product of women’s childrearing work. Tarbiya thus became essential to stabilizing the reproductive contradictions of modern social life in ways that later became difficult to see. The history of tarbiya reveals how gender difference allowed people to imagine work under capitalism, freedom under democratic governance, and cohesion in a society fragmented by many forms of social difference.

One way that the essential reproductive work of tarbiya has been hidden and undervalued in many places around the world is through the feminization of labor, a historical process through which people came to agree that reproductive work belonged to women in the home. Many of the men and women who theorized tarbiya in the Arabic press, by contrast, understood that upbringing and childrearing were not naturally associated with a timeless notion of the feminine. They recognized that the feminization of that labor was a “powerful, productive fiction” rather than a reflection of natural connections between sexed bodies and particular activities.67 Instead, writers, educators, and editors had to work to construct and maintain the growing consensus that tarbiya belonged to women. By assigning childrearing to women, writers argued that political and social reproduction took place outside of historical change, in a timeless realm of love and nature. They also placed childrearing beyond political contestation, locating it in a pre-political space framed not by free, rational, and self-owning agents but by unchosen, embodied connections between mother and child. By feminizing tarbiya, they redefined what it meant to be a woman and a political subject in the Arab world.

The questions tarbiya raised among writers working in Arabic between 1850 and 1939 resonated across both time and space. After World War II, for example, feminists around the world would return to the importance of women’s reproductive labor as part of fights for justice and emancipation, albeit in a different register. In the 1970s, women from Italy, Canada, and the United States came together to demand “wages for housework.”68 They argued that women’s work as housewives was essential to the production of surplus value under capitalism.69 Surplus value is the difference between the value of what workers produce and what they are paid as a wage; that difference, which is captured by the owner class, is what allows capital to accumulate. Without women’s unpaid work in cooking, cleaning, childbirth, and childrearing in the “social factory,” the owner class would have to pay the true price for reproducing their workforce, causing surplus value to diminish or even disappear.70 By demanding wages for otherwise unpaid domestic labor, the Wages for Housework campaign sought to bring women together as a class to destroy the gendered division of labor that makes capitalism possible.

Contemporary feminist theorists also turn to the unpaid work of care and reproduction to highlight the “crisis tendencies,” or internal contradictions, of capitalist society. Nancy Fraser, for example, has written about how capitalism’s search for unlimited accumulation destabilizes the very processes of social reproduction that allow for that accumulation in the first place.71 As owners seek to squeeze more and more value out of labor, they make it more and more difficult to reproduce and maintain the workforces that they depend on. Simply put, the more people work for others and the less they earn, the harder it becomes to cook, wash, have sex, or rear children, that is, to sustain the labor power that capitalism requires.

Motherhood is not, however, simply another repository of value to be captured by capital. As feminist theorists Patricia Hill Collins and Alexis Pauline Gumbs have shown, expanded practices of mothering have long enabled racialized and minoritized people to constitute communities and imagine better futures. For them, mothering has been a site of revolutionary world-building rather than an “immature” form of political activism.72 At the same time, they remind us to notice how normative ideals of motherhood reproduce social difference based on race, class, ability, sexuality, and geography, among other categories.73 As Loretta Ross and Rickie Solinger remind us, “the nobility of white, middle-class maternity [has depended] on the definition of others as unfit, degraded, and illegitimate.”74 Asking who can mother, under what conditions, and whom ideals of family formation and motherhood benefit and exclude remains essential to any consideration of reproductive labor, past or present. In the Arab East at the turn of the twentieth century, new norms of motherhood and family elevated educated middle-class women to positions of power and authority but had very different implications for those who did not meet their terms.

The history of tarbiya allows us to bring these persistent questions about the uneven, unequal work of mothering and social reproduction under capitalism together with questions about what I call political reproduction: the reproduction of free, trustworthy subjects for popular sovereignty and representative politics. This kind of reproduction is important for representative governments because they require citizens who can be trusted to govern and administer themselves in predictable ways, often oriented toward maintaining the power of existing elites. By highlighting the importance of political reproduction to representative democracies, the history of tarbiya offers a new explanation for the gendered exclusions of liberal politics. By liberal politics, I mean political systems premised on the autonomous, self-owning subject whose freely chosen vote legitimates the power of the state. Feminist critics of liberalism have debated why women were so frequently excluded from early experiments in representative governance, for example in the United States after 1776 or in France after 1789. One answer is that these states, and the ideas of liberty and social contract they invoked, were inherently patriarchal from the beginning: civil freedom has always been premised on men’s preexisting patriarchal right to subordinate women.75 Another answer is that liberalism fundamentally relies on an understanding of equality as sameness; women, then, are easily excluded because they appear different from the men whose bodies and experiences constitute the “neutral standard of the same.”76 This tension, in turn, produces the constitutive “paradox” at the heart of liberal feminism, which has had to make claims to universal categories of political subjecthood based on the premises of gender particularity.77 In other words, women have to argue as women for the universal rights that would make the category of “woman” politically irrelevant.

The story of tarbiya offers a new explanation for why liberal political regimes have relied so heavily on gender difference to draw the boundaries of equality and political personhood. Tarbiya suggests that the answer to this question lies in the feminization of political as well as social reproduction. As theorists of tarbiya recognized, maintaining the fantasy of the self-owning liberal subject as free to make his own choices requires the feminization and privatization of political-reproductive work. If political subject formation and moral cultivation is to be the work of women in the home, those women and that home space cannot be allowed to enter the formal space of the political. Otherwise, the fantasy of human equality that undergirds discourses of equal rights and protections under the law would fall apart. In effect, women’s essential contributions to raising people fit to participate in representative democracy have had to be hidden to maintain the argument that freedom and equality are inherent human characteristics. If people are not forged by birth alone but also by women’s work in early childhood, how can they be born equal or free?

Today, in light of feminist calls to attend to a broader “crisis of care” that pulls racialized women from the Global South to perform reproductive labor in and for the Global North, whether as housemaids or surrogates, tarbiya reminds us that these questions are not unique to late capitalism or to the particular terrain of global labor migration that has emerged since the 1970s.78 Tarbiya teaches us to attend to how the feminization of particular kinds of labor—civilizational, political, and social—has long shaped our categories of man and woman, rather than the other way around. Finally, tarbiya shows that the question of reproduction has always had political as well as social and physiological dimensions, by highlighting the reproductive contradictions of the liberal political subject alongside the illusory freedom of the adult man working for a wage. Women’s labor as childrearers has often been called on as a nonpolitical location to resolve those contradictions before the adult male subject/worker goes out into the world. This book turns to the history of tarbiya to show how people understood and theorized that process in one particular location. This is not to suggest that words alone will be enough to change our current conditions, that if we somehow construct better theory or uncover better concepts, change will surely follow. But widening our conceptual vocabularies for understanding shared and stubborn problems—in this case, the devaluation of social reproduction under capitalism and the stubborn maleness of the supposedly universal liberal subject—might help us think more collectively and imaginatively about where to go from here.

1. Dimashqiyya, “Ila Ibnat Biladi,” al-Marʾa al-Jadida (June 1924): 231.

2. Dimashqiyya, 231.

3. Dimashqiyya, 230.

4. Dimashqiyya, 232.

5. Elizabeth Thompson, “Public and Private in Middle Eastern Women’s History,” Journal of Women’s History 15, no. 1 (2003): 52–69.

6. Fruma Zachs and Sharon Halevi, “From Difaʿ al-Nisaʾ to Masʾalat al-Nisaʾ: Readers and Writers Debate Women and Their Rights, 1858–1900,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 41, no. 4 (2009): 617–21.

7. The term Mashriq also sometimes encompasses Sudan and the countries of the Arabian Gulf.

8. On migration between Greater Syria and Egypt, see Masʿud Dahir, Hijrat al-Shawwam: al-Hijra al-Lubnaniyya ila Misr (Beirut: al-Jamiʿa al-Lubnaniyya, 1986).

9. Ilham Khuri-Makdisi, “The Conceptualization of the Social in Late Nineteenth-and Early Twentieth-Century Arabic Thought and Language,” in A Global Conceptual History of Asia, 1860–1940, ed. Hagen Schulz-Forberg (New York: Routledge, 2014), 263.

10. Labiba Hashim’s Fatat al-Sharq was distributed in schools, while the Egyptian Ministry of Education distributed Balsam ʿAbd al-Malik’s al-Marʾa al-Misriyya and Labiba Ahmad’s al-Nahda al-Nisaʾiyya to government girls’ schools. Schoolgirls also read earlier women’s journals, sometimes purchased for them by the Egyptian royal family. Marilyn Booth, May Her Likes Be Multiplied: Biography and Gender Politics in Egypt (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 112.

11. Andrew Sartori, Bengal in Global Concept History: Culturalism in the Age of Capital (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 10; Sartori, “Global Intellectual History and the History of Political Economy,” in Global Intellectual History, ed. Samuel Moyn and Sartori (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013), 123.

12. I borrow this useful formulation from Gary Wilder, Freedom Time: Negritude, Decolonization, and the Future of the World (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2015), 3.

13. This extends the call to consider individual (often male and postcolonial) Arab thinkers as theorists rather than exemplars. Omnia El Shakry “Rethinking Arab Intellectual History: Epistemology, Historicism, Secularism,” Modern Intellectual History 18 (2021): 550; Hosam Aboul-Ela, “The Specificities of Arab Thought: Morocco since the Liberal Age,” in Arabic Thought against the Authoritarian Age: Towards an Intellectual History of the Present, ed. Jens Hanssen and Max Weiss (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 143–62; Fadi Bardawil, Revolution and Disenchantment: Arab Marxism and the Binds of Emancipation (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020).

14. Nancy Fraser argues that reproduction is “behind” and “more hidden still” than the abode of production hidden in Marx. Fraser, “Behind Marx’s Hidden Abode: For an Expanded Conception of Capitalism,” New Left Review 86 (Mar./Apr. 2014): 57.

15. Fraser, “Behind Marx’s Hidden Abode,” 57.

16. For Marx, labor appears as a process in which “man’s activity, with the help of the instruments of labour, effects an alteration, designed from the commencement, in the material worked upon. The process disappears in the product, the latter is a use-value, Nature’s material adapted by a change of form to the wants of man.” Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 1, trans. Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling (Moscow: Progress, 1887), 128.

17. Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), 16.

18. Margrit Pernau suggests something similar in “Provincializing Concepts: The Language of Transnational History,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 36, no. 3 (2016): 483–99.

19. Susan Buck-Morss calls this “the communism of the idea” in “The Gift of the Past,” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 14, no. 3 (2010): 183.

20. Omnia El Shakry describes how tarbiya articulated with adab, the “complex of valued dispositions (intellectual, moral, and social), appropriate norms of behavior, comportment, and bodily habitus.” El Shakry, “Schooled Mothers and Structured Play: Child Rearing in Turn-of-the-Century Egypt,” in Remaking Women: Feminism and Modernity in the Middle East, ed. Lila Abu-Lughod (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998), 127. On the broader nineteenth-century revival of classical texts, see Ahmed El Shamsy, Rediscovering the Islamic Classics: How Editors and Print Culture Transformed an Intellectual Tradition (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020).

21. Theodore Zeldin, France, 1848–1945, vol. 2, Intellect, Taste and Anxiety (Oxford: Clarendon, 1977), 139.

22. Linda Kerber, Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997); Mary Ryan, Empire of the Mother: American Writing about Domesticity, 1830–1860 (New York: Harrington Park, 1985); Christina de Bellaigue, Educating Women: Schooling and Identity in England and France, 1800–1867 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007); Anna Davin, “Imperialism and Motherhood,” History Workshop 5 (1978): 9–65.

23. Sartori, Bengal in Global Concept History, 26–34.

24. Norbert Elias, The Civilizing Process: The History of Manners, ed. Eric Dunning, Johan Goudsblom, and Stephen Mennell, trans. Edmund Jephcott (Malden: Blackwell, 2000), 368; Reinhart Koselleck, “On the Anthropological and Semantic Structure of Bildung,” in The Practice of Conceptual History: Timing History, Spacing Concepts, trans. Todd Samuel Presner et al. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002), 174. While I emphasize resonances across boundaries of language and geography, Koselleck’s essay emphasizes the difficulty of finding precise analogs for bildung in other languages.

25. Rich scholarship charts the creative translation of Euro-American concepts and debates in the non-West. For example, see Marwa Elshakry, Reading Darwin in Arabic, 1860–1950 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013); Ilham Khuri-Makdisi, The Eastern Mediterranean and the Making of Global Radicalism, 1860–1914 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010); Lydia Liu, Translingual Practice: Literature, National Culture, and Translated Modernity—China, 1900–1937 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995).

26. Sartori, Bengal in Global Concept History, 19.

27. This approach is inspired by Holly Case’s The Age of Questions (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018), which argues that the “question” form itself was characteristic of nineteenth-century thought.

28. Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe; Ussama Makdisi, “Ottoman Orientalism,” American Historical Review 107, no. 3 (2002): 768–96.

29. Khuri-Makdisi, “Conceptualization of the Social,” 93. On debt, see Aaron Jakes, Egypt’s Occupation: Colonial Economism and the Crises of Capitalism (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2020).

30. Timothy Mitchell, Colonizing Egypt (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 119.

31. Ussama Makdisi, The Culture of Sectarianism: Community, History, and Violence in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Lebanon (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000); on earlier peasant revolts in Lebanon, see Fawwaz Traboulsi, A History of Modern Lebanon (New York: Pluto, 2007); on Egypt, see Zeinab Abul-Magd, Imagined Empires: A History of Revolt in Egypt (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013).

32. Khuri-Makdisi, “Conceptualization of the Social,” 93; John Chalcraft, The Striking Cabbies of Cairo and Other Stories: Crafts and Guilds in Egypt, 1863–1914 (Albany: SUNY Press, 2004); Abul-Magd, Imagined Empires.

33. Timothy Mitchell, Colonizing Egypt, 119.

34. Khuri-Makdisi, “Conceptualization of the Social,” 99.

35. In Arabic, ḥukm [al-umma] li-nafsihā bi-nafsihā. Rashid Rida, “Khutba fi-l-Majalis al-Umumiyya bi-l-Wilayat,” al-Manar 12, no. 2 (22 Mar. 1909): 108.

36. Ali Yaycioglu, Partners of the Empire: The Crisis of the Ottoman Order in the Age of Revolutions (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016); Linda Darling, A History of Social Justice and Political Power in the Middle East: The Circle of Justice from Mesopotamia to Globalization (New York: Routledge, 2013), chap. 9.

37. Alice Conklin, A Mission to Civilize: The Republican Idea of Empire in France and West Africa, 1895–1930 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997); Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe; Makdisi, “Ottoman Orientalism.”

38. Mary Poovey, Making a Social Body: British Cultural Formation, 1830–1864 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995); Andrew Barshay, The Social Sciences in Modern Japan: The Marxian and Modernist Traditions (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007); Rachel Sturman, The Government of Social Life in Colonial India: Liberalism, Religious Law, and Women’s Rights (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012); Kai Vogelsang, “Chinese ‘Society’: History of a Troublesome Concept,” Oriens extremus 51 (2012): 155–92; see also Schulz-Forberg, Global Conceptual History.

39. The literature here is vast; works I’ve found especially helpful include Kathleen Uno, Passages to Modernity: Motherhood, Childhood, and Social Reform in Early Twentieth Century Japan (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1999); Mytheli Sreenivas, Reproductive Politics and the Making of Modern India (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2021); Firoozeh Kashani-Sabet, Conceiving Citizens: Women and the Politics of Motherhood in Iran (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011); Margaret Tillman, Raising China’s Revolutionaries: Modernizing Childhood for Cosmopolitan Nationalists and Liberated Comrades, 1920s–1950s (New York: Columbia University Press, 2018); Joshua Hubbard, “The ‘Torch of Motherly Love’: Women and Maternalist Politics in Late Nationalist China,” Twentieth-Century China 43, no. 3 (2018): 251–69.

40. Wilder, Freedom Time, 9–10.

41. Edward W. Said, “Traveling Theory,” in The World, the Text, and the Critic (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1983), 241.

42. Said, “Traveling Theory,” in The World, the Text, and the Critic, 241.

43. Beth Baron, The Women’s Awakening in Egypt: Culture, Society, and the Press (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994), 1. In 1903, Cairo-based women’s journal al-Sayyidat wa-l-Banat boasted 1,100 subscribers. Ami Ayalon, The Press in the Arab Middle East: A History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 45.

44. Baron, Women’s Awakening, 90–93; Elizabeth Thompson, Colonial Citizens: Republican Rights, Paternal Privilege, and Gender in French Syria and Lebanon (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 212–13.

45. In Egypt, literacy increased from 11.2 percent of men and 0.3 percent of women in 1897 to 23 percent of men and 4.9 percent of women in 1927. Hoda Yousef, Composing Egypt: Reading, Writing, and the Emergence of a Modern Nation, 1870–1930 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016), 19. In Lebanon, literacy rates were about 60 percent by 1930, and there were nearly as many literate women as men in the major cities. Thompson, Colonial Citizens, 212. Official literacy rates likely underrepresented the number of people who accessed reading and writing in different ways, including through scribes and listening to others read aloud. Yousef, Composing Egypt, 46.

46. The classic history of men’s thought in Arabic remains Albert Hourani, Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age, 1798–1939 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1983; orig. 1962).

47. Wilson Chacko Jacob charts the normalization of heterosexuality as key to Egyptian modernity in Working Out Egypt: Effendi Masculinity and Subject Formation in Colonial Modernity, 1870–1940 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011); on the heterosexualization of love in Iran, see Afsaneh Najmabadi, Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iranian Modernity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).

48. Joan W. Scott, “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis,” American Historical Review 91, no. 5 (1986): 1056.

49. Anne Fausto-Sterling, Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality (New York: Basic Books, 2000); Rebecca Jordan-Young, Brain Storm: The Flaws in the Science of Sex Differences (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011); Sarah Richardson, “Sexing the X: How the X Became the ‘Female Chromosome,’” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 37, no. 4 (2012): 909–33.

50. Marilyn Booth’s work on Zaynab Fawwaz shows how close reading, archival sleuthing, and “deep listening” can yield rich works of feminist biography. Booth, The Career and Communities of Zaynab Fawwaz: Feminist Thinking in Fin-de-Siècle Egypt (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), 16.

51. Yousef, Composing Egypt, esp. chap. 2; Baron, Women’s Awakening, 39–50.

52. Baron, Women’s Awakening, 13. Women memoirists like Huda Shaʿrawi, ʿAnbara Salam Khalidi, and Julia Dimashqiyya are welcome exceptions to this generalization.

53. Marilyn Booth, “Liberal Thought and the ‘Problem’ of Women: Cairo, 1890s,” in Hanssen and Weiss, Arabic Thought against the Authoritarian Age, 187.

54. Peter de Bolla, The Architecture of Concepts: The Historical Formation of Human Rights (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 21–23.

55. Audre Lorde, “Poetry Is Not a Luxury,” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Trumansburg: Crossing Press, 2007; orig. 1984), 38.

56. Fruma Zachs and Sharon Halevi, Gendering Culture in Greater Syria: Intellectuals and Ideology in the Late Ottoman Period (New York: I.B. Tauris, 2015), 16–41.

57. Hoda Yousef, “The Other Legacy of Qasim Amin: The View from 1908,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 54, no. 3 (2022): 505–23.

58. Zachs and Halevi, Gendering Culture, 16–41; in 1858, a group of women from Tripoli published a letter in Hadiqat al-Akhbar in response to an article accusing women of being quick to transmit information (16).

59. On nationalism, see Beth Baron, Egypt as a Woman: Nationalism, Gender, and Politics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007); Laura Bier, Revolutionary Womanhood: Feminisms, Modernity, and the State in Nasser’s Egypt (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011); Hanan Kholoussy, For Better, for Worse: The Marriage Crisis That Made Modern Egypt (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010). On imperialism, see Marilyn Booth, “Peripheral Visions: Translational Polemics and Feminist Arguments in Colonial Egypt,” in Edinburgh Companion to the Postcolonial Middle East, ed. Anna Ball and Karim Mattar (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018), 183–212; Lisa Pollard, Nurturing the Nation: The Family Politics of Modernizing, Colonizing, and Liberating Egypt, 1805–1923 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005). On commodity capitalism, see Mona Russell, Creating the New Egyptian Woman: Consumerism, Education, and National Identity, 1863–1922 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004); Toufoul Abou-Hodeib, A Taste for Home: The Modern Middle Class in Ottoman Beirut (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017).

60. Marilyn Booth, May Her Likes Be Multiplied: Biography and Gender Politics in Egypt (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001); Booth, Classes of Ladies of Cloistered Spaces: Writing Feminist History through Biography in Fin-de-Siècle Egypt (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015); Booth, Fawwaz; Boutheina Khaldi, Egypt Awakening in the Early Twentieth Century: Mayy Ziyadah’s Intellectual Circles (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

61. Baron, Women’s Awakening; Margot Badran, Feminists, Islam, and Nation: Gender and the Making of Modern Egypt (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995); Booth, May Her Likes Be Multiplied; Booth, Classes of Ladies; Booth, Fawwaz; Thompson, Colonial Citizens.

62. Booth, Fawwaz, 3, 9.

63. Joan Wallach Scott, The Fantasy of Feminist History (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 33.

64. Lila Abu-Lughod, “Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving? Anthropological Reflections on Cultural Relativism and Its Others,” American Anthropologist 104, no. 3 (2002): 783–90.

65. Scott, Fantasy of Feminist History, 33.

66. Booth, Fawwaz, 6.

67. Sharad Chari, Fraternal Capital: Peasant-Workers, Self-Made Men, and Globalization in Provincial India (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004), 241.

68. On Wages for Housework, see Louise Toupin, The History of the Wages for Housework Campaign (London: Pluto, 2018).

69. Mariarosa Dalla Costa and Selma James, The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community (Bristol: Falling Wall, 1972); Sylvia Federici, Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle (Brooklyn: PM Press, 2012).

70. Dalla Costa and James, Power of Women, 3.

71. Fraser, “Crisis of Care,” in Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression, ed. Tithi Bhattacharya (New York: Pluto, 2017), 21–36. See also Maria Mies, Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale: Women in the International Division of Labour (London: Zed Books, 2014; New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 1986); Dalla Costa and James, Power of Women.

72. Patricia Hill Collins, “Black Women and Motherhood,” in Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment (Boston, Unwin Hyman, 1990), 194; Kaila Adia Story, ed., Patricia Hill Collins: Reconceiving Motherhood (Bradford, Ontario: Demeter, 2014); Alexis Pauline Gumbs, “‘We Can Learn to Mother Ourselves’: The Queer Survival of Black Feminism” (PhD diss., Duke University, 2010).

73. Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Diacritics 17, no. 2 (1987): 65–81; Alexis Wells-Oghoghomeh, The Souls of Womenfolk: The Religious Cultures of Enslaved Women in the Lower South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021); Dorothy Roberts, Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty (New York: Vintage Books, 1998); Loretta Ross and Rickie Solinger, Reproductive Justice: An Introduction (Oakland: University of California Press, 2017); Alexis Pauline Gumbs, China Martens, and Mai’a Williams, eds., Revolutionary Mothering: Love on the Front Lines (Berkeley: PM Press, 2016), 9–11.

74. Ross and Solinger, Reproductive Justice, 4.

75. Carole Pateman, The Sexual Contract (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988), 3; see also Lynn Hunt, The Family Romance of the French Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992).

76. Wendy Brown, States of Injury: Power and Freedom in Late Modernity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995), 153.

77. Joan Wallach Scott, Only Paradoxes to Offer: French Feminists and the Rights of Man (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997).

78. Fraser, “Crisis of Care;” see also Mignon Duffy, Making Care Count: A Century of Gender, Race, and Paid Care Work (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2011).