A rabbi’s son in Essaouira, Morocco, writes a scathing, phantasmagorical poem about Hitler’s rise to power, only to burn every copy out of fear. An adolescent in Italian Tripolitania ponders the meaning of her Jewishness as fascism gains favor in her community and war threatens the world. A Moroccan Jewish cinema owner is compelled by French Vichy race laws to sell his business to a Christian peer. A Muslim nationalist in Tunisia is hounded, arrested, and interned by the same regime for his political views. A Polish erstwhile volunteer for the International Brigade in Spain is forced to labor on an aspirational trans-Saharan railroad day after day without shoes. Drunken German soldiers and SS officers terrorize the Jewish women of Nazi-occupied Tunis, threatening them with sexual violence. Families across Algeria starve as drought and famine overcome rural communities. A German Jewish photojournalist snaps pictures of the Moroccan infantrymen who guard his internment camp in the desert. A young boy watches Operation Torch, the Allied military campaign to liberate North Africa from the Axis powers, unfold outside his seaside window. A top-ranked Algerian Jewish water-polo player is reported annihilated by the Nazis in the Auschwitz death camp, only to make a shocking return to the competitive stage. The future president of Senegal—a poet, theorist, and anticolonial activist—languishes in a prisoner-of-war (POW) camp in France, incensed at the racial inequities that undergird French military policy. A survivor of the Nazi death camps returns to his native Tlemcen, Algeria, bearing a numerical tattoo on his arm that none can decode. An ashkeva (memorial prayer) is composed to memorialize the murdered of Tunisia.

This is wartime North Africa, seen not from the vantage of state policy or military engagements but from the viewpoint of the diverse people who lived it.

During the Second World War, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya witnessed Vichy, Nazi, and Italian fascist rule as well as Spanish control; the implementation of racist and anti-Semitic laws; the theft of property, assets, and businesses; the influx of huge numbers of refugees from Europe; and the mass internment in forced labor and internment camps of women, men, and children of North African, European, and global origin.1 Some North Africans (Muslims as well as Jews) were deported to Nazi camps from North Africa—in the case of Libyan Jews, by way of internment in Italy.2 Other North African Jewish émigrés living in France were deported to labor, internment, and death camps by the Nazi regime, with the help of the French authorities.3 The Nazis also imprisoned North African and West African soldiers who served under the French flag in POW internment camps in France.4

Until now, personal histories of wartime North Africa have remained largely inaccessible to English-language readers.5 To the extent that these stories have been told, they have been narrated separately, which has led to the deceptive perception that the many, varied experiences of wartime North Africa (whether experienced by local Jews or Muslims, European refugees, former volunteers for Spain’s International Brigade or France’s Foreign Legion, the interned and forced laborers, French “colonial soldiers” from North and West Africa, or others) were discrete phenomena. In this book, these stories are reunited. Here, readers will encounter wartime North Africa in all its diversity, and on a human scale.

To create this book, we have plumbed archives, libraries, and private collections across North Africa and West Africa, the Middle East, Europe, and the Americas. A number of our selections are drawn from published books (memoirs, diaries, collections of poetry, and more), but most have never been published before or translated into English. Translated from French, Arabic, North African Judeo-Arabic, Spanish, Hebrew, Moroccan Darija, Tamazight (Berber), Italian, and Yiddish, or transcribed from their original English, these sources are like the dots of a pointillist painting. Each is unique and distinct—yet together they form an arresting whole.

Who made up wartime North Africa, that is, the present-day countries of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya?6 The cast of characters that populate this book is diverse, not only because the Maghrib itself was a region always marked by diversity but also because, in the years leading up to and during the Second World War, its population swelled with officers, bureaucrats, and soldiers foreign and native; émigrés, refugees, and the displaced; internees, prisoners of war, and camp guards; philanthropic representatives; and more.

There was, to begin, an autochthonous Muslim population of roughly twenty million and a smaller Jewish population numbering roughly five hundred thousand in the Maghrib, each of which was multifarious in its own right. These populations shared courtyards and cities, as well as coastal, desert, and mountain towns; they were each, also, internally striated by class, history, language, and religious practice and ritual.7

North Africa’s Jews lived in distinct, yet porous ethnic quarters or communal spaces alongside Muslims in both the urban and the rural regions of North Africa: the mellah (in Morocco and parts of western Algeria) and the hara of Algeria, Tunisia, and Tripolitania in northwestern Libya. In rural and mountainous regions of North Africa that were predominantly Berber/Amazigh and Arab, Jews and Muslim tended to live in a more integrated fashion.8 Increasingly, a segment of North Africa’s urban Jews lived in mixed middle- and upper-class neighborhoods, mingling easily with their city’s multiethnic and multisectarian bourgeoisie.

Prewar North Africa also housed a population of European settler colonialists. These women, men, and children came from a variety of backgrounds—French, Sicilian, Italian, Maltese—and had been in the Maghrib for different lengths of time: in some cases for generations, in other cases only a few years. In all instances, their arrival in the region was in various respects subsidized and encouraged by the European colonial and “civilizing” project. This so-called colon population was receptive to—and indeed themselves producers of—anti-Jewish and anti-Muslim rhetoric, and the settler colonialists sometimes translated these sentiments into physical violence, as during the Constantine riots of 1934.9

The residents of North Africa were spread across the countries and colonies of the prewar era: Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya. Subject to a violent colonization that had begun in the early nineteenth century, most of Algeria was integrated into France in 1848, but the state emancipated few Algerian Berber or Arab Muslims, who were categorized as “indigenous subjects of France” rather than French citizens. Since 1870, the bulk of Algeria’s indigenous Jews were placed in another legal category by the Crémieux Decree, which granted them citizenship (excepting the small population in the military districts of the Sahara).10 Morocco and Tunisia, by contrast, were protectorates of France, and here both Muslims and Jews were considered subjects of the sultan and bey (respectively), except for a minority of Jews who obtained French or Italian or other foreign citizenship.11 The Libyan provinces of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica came under Italian control by treaty in 1912, a year after Italy became embroiled in a war with the Ottoman Empire over the region. Over the ensuing two decades, the Italian army gained control of the remainder of Libya through a brutal conquest overseen, as of 1922, by Benito Mussolini and his National Fascist Party. Fascist Italy granted Libya’s residents colonial legal status as “Libyan Italian citizens.”12 Yet there, as across North Africa, a small but powerful percentage of Jewish women, men, and children (and smaller numbers of Muslims) held European or other foreign citizenship, in some cases because they worked for foreign consuls. Under colonialism, such an “extraterritorial” legal status afforded opportunities, but under Vichy, Nazi, and fascist Italian rule it could prove a legal liability.

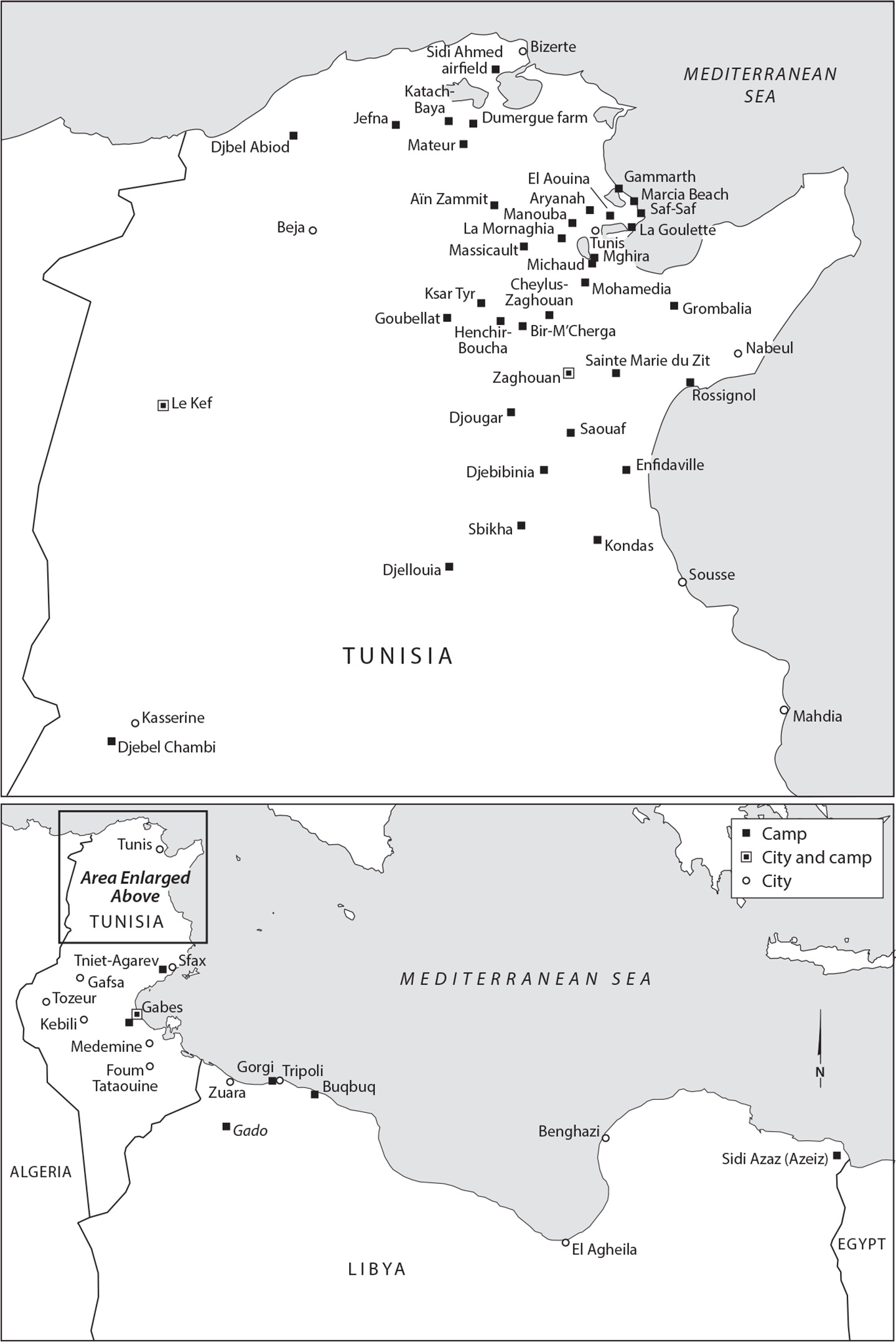

The European powers had maintained a presence in the Maghrib since the early modern period, but with the colonization of Algeria and Tunisia in the nineteenth century, and Morocco and Libya in the early twentieth, the number of French, Spanish, and Italian people in the region soared. During the Second World War these numbers increased further to encompass military and civilian representatives, including Nazi SS (Schutzstaffel, or paramilitary) officers and German soldiers who occupied Tunisia for six months between November 1942 and May 1943.13 State power could make itself felt in a violent fashion, of course, but also through pageantry. As sources in this book reveal, the Italian prime minister Benito Mussolini undertook a grandiose visit to Tripoli’s Jewish neighborhood in 1937, while in French North Africa, teachers were required to hang portraits of Marshal Philippe Pétain (head of wartime France’s collaborationist Vichy regime) in their classrooms.

As Nazism and fascism gained favor and power in Europe and across the colonial world, the residents of North Africa were watching.14 But North Africans were not passive observers or hapless victims of these trends. They were, instead, actively caught up in history as oracles, critics, resistance fighters, soldiers, narrators, translators, philanthropists, and religious leaders. As businesspeople and professionals, they maneuvered to keep their places of employment and jobs in the face of racist restrictions. As mothers, they sought the best for children living under duress. As prisoners, they maintained dignity through comradery, reading, writing, prayer, and producing art. As Black and/or colonial soldiers they braved the harshest military assignments and voiced outrage against the racist disrespect of the country whose flag they served.15 As anticolonialists, they either welcomed or resisted Axis occupation (depending upon their view of French colonial rule) and, later, the arrival of Allied forces who sought to “liberate” North Africa. As religious leaders, they composed prayers, psalms, and eulogies, helping others to remember, to memorialize, and to heal.

Our first source dates to 1934, a year after Germany’s president Paul von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler, leader of the Nazi Party, as chancellor of Germany and a moment when the Nazi leadership was brutally consolidating its power. In Meknes, Morocco, a Moroccan Jewish teacher by the name of Prosper Cohen watched Hitler’s rise with horror. Likening the Nazi leader to Haman (the fourth-century enemy of Persian Jewry and the villain of the Purim story), Cohen wrote that the Nazis’ rise signaled the precarity of Jews everywhere—even North Africa. Five years later, in 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Poland, initiating the Second World War. Then, another Moroccan Jew from the city of Essaouira (Mogador) echoed Cohen’s dark warning. In a fantastical poem that he self-published and distributed (before destroying every available copy in a state of panic), Isaac Knafo presaged ruin for the world. Writing at the same time, a Muslim sheikh in Oran, Algeria, predicted the German conquest of North Africa and, with it, the defeat of French colonial armies.

Across North Africa, individuals initiated campaigns against the rise of Nazism and fascism, at times bonding into interfaith alliances that called for a boycott of Nazi-sympathizing businesses and settlers in North Africa’s cities.16 For, indeed, German attachés and representatives were using North Africa (and especially the Spanish zone of northern Morocco) as a base from which to spread anti-Semitic, anti-French, and anti-British, Arabic-language propaganda through radio, leaflets, and newspapers, at times with the help of allied Muslims. Meanwhile, in Europe, Jews of North African origin participated in the resistance against Nazi ideology and, later, against German and French race laws.

Other Europeans, too, were enacting their objection to the rise of Nazism and fascism, sometimes by fleeing to North Africa.17 Whether their origins were humble or notable, these refugees arrived penniless, contactless, and traumatized, with the nature and duration of their time in North Africa unknown. Alegria Bendelac, whose voice and image we encounter in the pages that follow, remembers being an economically privileged Jewish girl struggling to adjust to the influx of desperate European refugees into her native city of Tangier.

Migration could be a political choice, too. As the power of the Nazi party increased, thousands of European Jews (and some Christians, too) volunteered to serve the French Foreign Legion in its fight against Nazism. And a staggering thirty-five thousand volunteers from over fifty countries, including 3,500–4,000 Jews, flocked to Civil War–torn Spain to serve in the Republican Army’s International Brigade, fighting on behalf of the fledgling Spanish Republic and against the Nationalist, conservative allies of General Francisco Franco.18 When Spain fell to Franco and France to Germany, these émigré, volunteer soldiers found themselves vulnerable as political enemies and/or foreigners of the ascendent Francoist dictatorship and Vichy regime.19 Many International Brigade members fled to France only to be deported to prison, internment, and labor camps in North Africa (a topic we return to momentarily). The same destiny met many of the Jews who volunteered for the French Foreign Legion.

Racist, colonialist, violent legislation and policy had been imposed upon the peoples, cultural fabric, and land of North African since the early nineteenth century. With the expansion of the Second World War, this political foundation was overlaid with Italian fascist, Nazi, and Vichy law. Italian fascist rule took hold in Italy’s colony of Libya in 1922, when Benito Mussolini was appointed prime minister by King Emmanuel III. At this time, many Libyan Jews, like their Italian peers, threw in their cause with the fascist project, seeing it as an ambitious, progressive, nationalist endeavor. Their sentiments would shift by 1938, when Mussolini imposed the first anti-Jewish legislation in Italy and Libya. Jews were excluded from schools, the armed forces, and certain sectors of public employment: restricted in their ability to own property and confronted with greatly curtailed economic, social, and cultural activities. Jewish marriages to so-called Aryans were also prohibited by Italy. Watching the unfolding of race laws in her native Libya, the teenager Marie Abravanel mused in 1939 that her Jewishness marked her with “the stamp of shame.” Three years later, Mussolini would order the deportation of thousands of Libyan Jews to internment camps in Italy or Libya. Among the deportees were 870 Jewish holders of British passports. When Italy fell to Germany, a portion of that population was deported once again, to the Nazi camp of Bergen-Belsen.

In May 1940, Germany invaded France. But a month later, the aging First World War hero Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain signed an armistice with Germany on behalf of his country. The French-German Armistice of June 22, 1940, established German occupation over a zone in northern and western France, placing southern France under a new, collaborationist regime in the city of Vichy. With Pétain at its head, the Vichy government retained control over France’s colonies in Asia and Africa, including the protectorates of Tunisia and Morocco and colonial Algeria.20 In 1941, the Vichy regime established the Commissariat-General for Jewish Affairs, under the directorship of Xavier Vallat, to craft anti-Jewish legislation.21 Whatever racist and anti-Semitic laws and policies the Vichy regime would impose upon continental France, it also imposed upon its colonies in North Africa and West Africa: but these laws were implemented variously, as the exigencies of war interacted with the legal and political terrain of the prewar, colonial landscape.

In North Africa, the social and economic changes wrought by these changes were felt acutely. In the coastal city of El Jadida (Mazagan), a young boy by the name of David Bensimon watched his classroom change overnight. Jewish pupils were obliged to recite a poem honoring Pétain as the savior of Greater France. Pétain’s image literally looked down upon Bensimon and his classmates, as the French Department of Public Education had ordered schools to display photographs of Pétain in every classroom. Eugene Boretz’s wartime chronicles, represented in the pages that follow, describe Tunis as it passed from French to Italian and then German control. Boretz notes how the city was suddenly marked by new sounds and images, and that Jewish girls and women were newly vulnerable to sexual violence by the occupiers.

Beginning in the autumn of 1940, the Vichy regime subjected Jews in French North Africa to a version of the racist and anti-Semitic decrees that had been imposed in continental France. The Statut des Juifs, which had been modeled on Germany’s Nuremberg Laws, fixed a racial definition on Jews in France and Algeria, and stripped these French Jews of their citizenship. Other North African Jews were not directly affected by the revocation of citizenship; Moroccan, Tunisian, and Algerian Saharan Jews had been governed as indigenous subjects under French colonial rule and had no citizenship to be taken away. Yet across Vichy-controlled North Africa, quotas were imposed limiting the number of Jewish lawyers, teachers, students, doctors, and journalists. In Algeria, a group of Jewish doctors pleaded with their Muslim friends and colleagues to pressure Vichy representatives to allow them to practice medicine, noting that there was a typhoid epidemic killing Muslims in rural Algeria and their services were desperately required. To no avail.

So that the Vichy economy could be “Aryanized,” the state seized Jewish businesses, homes, and property. Jews from across North Africa flooded French bureaucratic agencies with passionate objections to these laws. Appealing from his native Fez, Raymond Bensimhon objected that his family had long supported the French colonial and civilizing mission. Remarkably, his petition was approved; Vichy authorities denied the majority of such requests. In such cases, North Africa’s Jews were forced to sell their property at a loss to European settlers and, in cases, to indigenous Muslims.

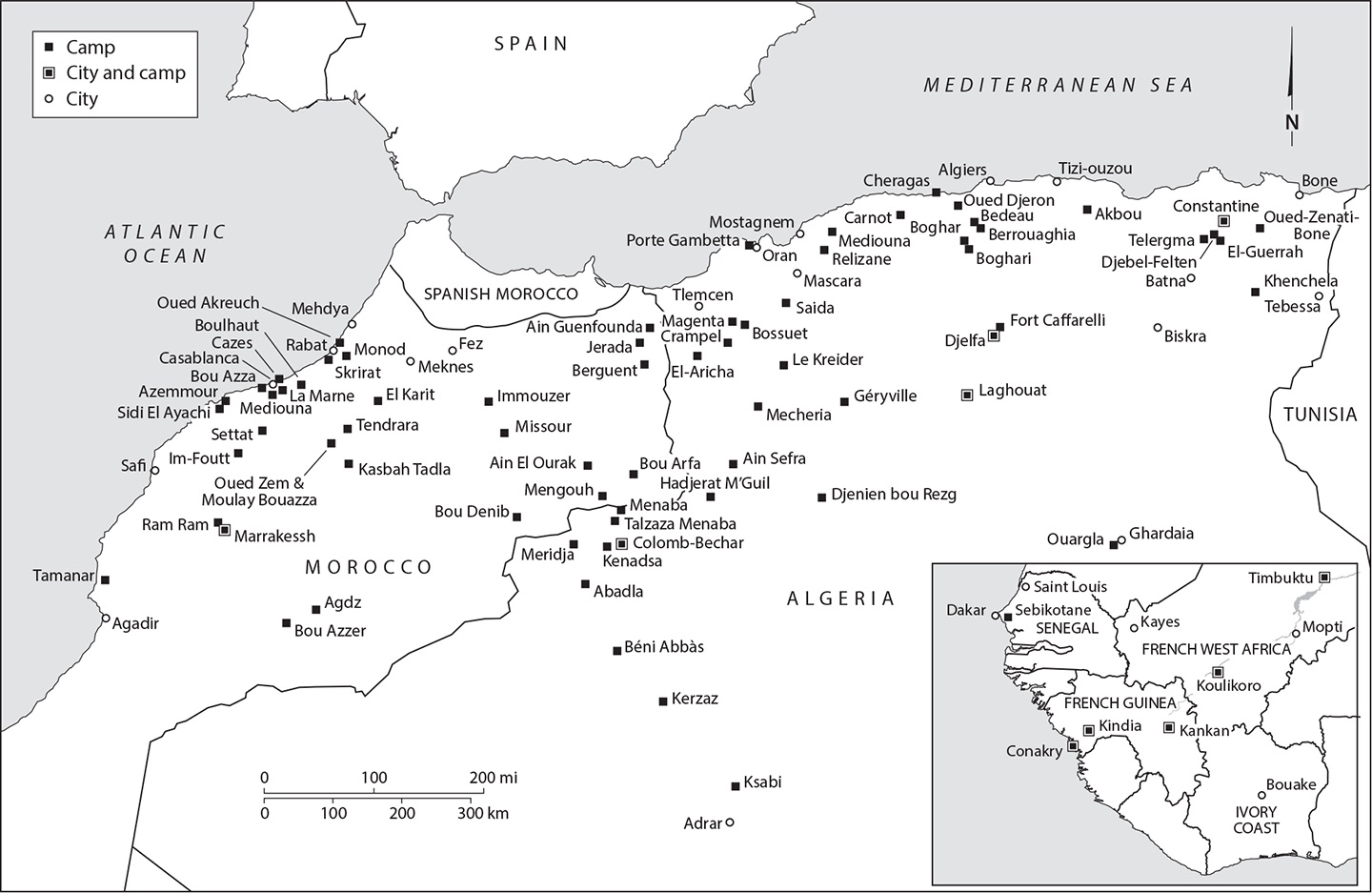

Soon after the German occupation of France, Pétain ordered the Vichy regime to build a network of penal, labor, and detention camps in West Africa and North Africa. Six detention camps were erected in West Africa and used to intern Allied prisoners of war and the crews of European military or commercial ships. Nearly seventy labor camps were built by the Vichy regime in the Sahara. These were centered on a project of the French colonial regime—of building a railroad that would span the Sahara, connecting the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts. In the colonial era, French authorities imagined a railroad connecting Dakar to the Mediterranean would move valuable goods and resources: the Vichy authorities emphasized that such a rail line could also supply a population of forcibly recruited Senegalese soldiers to the front lines, an ambition the Nazi authorities eagerly backed. To staff this massive infrastructural project, the Vichy Interior Ministry began, in 1940, to deport to the Saharan labor camps so-called undesirables and foreigners from France.22 Once interned, the political prisoners and internees were organized into groups of foreign workers under the charge of the French Ministry of Industrial Production and Labor. The dizzying mélange of internees in the Sahara included former volunteers for the Spanish International Brigade, former Jewish volunteers of the French Foreign Legion, Muslim and French political prisoners, Algerian Jewish veterans, and more. The interned were allowed access to humanitarian relief and assistance by the Vichy regime, and several organizations, in particular, were important in bettering their fate. Under the leadership of the tireless Moroccan Jewish lawyer Hélène Cazes Benatar, the Refugee Aid Committee in Casablanca cooperated with international service organizations such as HICEM (the Paris-based, combined offices of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society of New York and the Jewish Colonization Association of London), the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, and the American Friends Services Committee (a Quaker organization) to make life bearable for internees, both before and after the Anglo-American landing.23

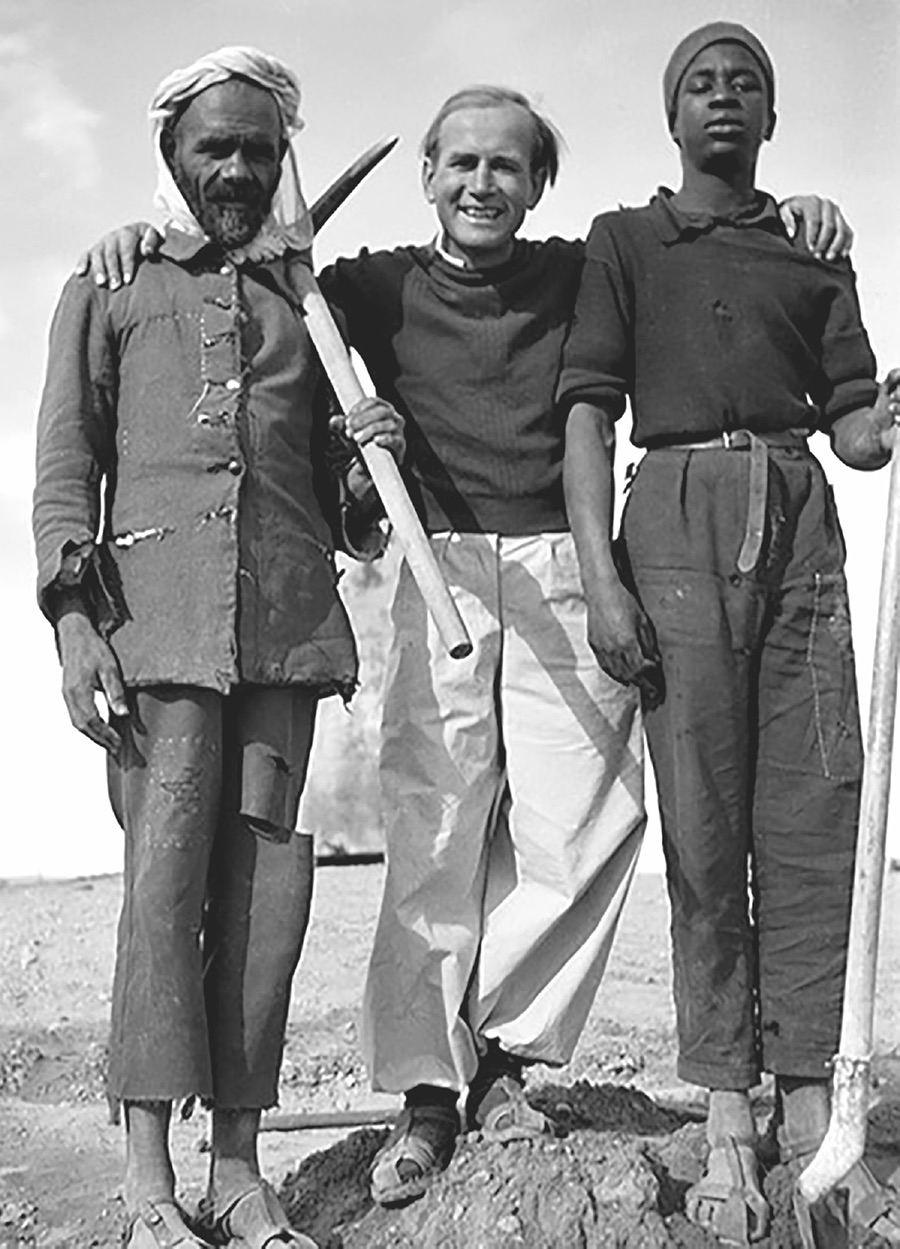

While the Saharan camps were overseen by soldiers from France, many guards were indigenous Moroccan infantry (goumiers), from indigenous tribal Moroccan and Algerian cavalry regiments (spahis), and Black colonial soldiers from Senegal, French Guinea, Ivory Coast, Dahomey, Senegambia, Niger, Upper Volta (Burkina Faso), and Mauritania (Senegalese tirailleurs), as well as light infantry units of Moroccan, Algerian, and sometimes Tunisian soldiers (also called tirailleurs). These soldiers, who served the French flag during colonial military campaigns and the First World War, were in most cases forcibly recruited and scarcely more than prisoners themselves. We follow the fate of some of these young men—including the towering figure of Léopold Senghor, theorist, poet, politician, and first president of the independent nation of Senegal—to the front lines and German prisoner-of-war camps, unpacking their racist, cruel treatment by France and Germany.

The choice to include within this volume the perspective of West African subjects of the Vichy regime is an intentional one. Vichy-controlled West Africa and its subjects were integrally related to wartime North Africa and its resident, refugees, and prisoners. Senegalese soldiers and their families had lived in North Africa since the interwar period, in cases becoming citizens of Morocco. During the Second World War, Senegalese tirailleurs served as guards in Vichy camps across North Africa, and they were dispatched to labor on regional infrastructural projects such as road building. West African soldiers were also dispatched to front lines, becoming among the first military victims of German assaults. Finally, the inclusion of Senegalese voices in this volume helps illustrate the racial logic of the Vichy regime, for which anti-Blackness and anti-Semitism were part of a comprehensive racist, Nazi-aligned logic with roots in European colonialism.

Diverse sources in this documentary history speak to the quotidian experience of life in the Vichy camps of North Africa. From them, we learn of women, children, and men of diverse backgrounds struggling to obtain proper nourishment, shelter, clothing, and shoes: of their struggles with disease, sleep deprivation, severe weather conditions, and pests such as lice, snakes, and scorpions. Drawn from memoirs, poetry, letters, and images, these sources reveal the systematic use of torture within the labor camps, as well as the Vichy strategy of moving prisoners from camp to camp, and between labor and penal camps, in an effort to disorient and rupture solidarities among prisoners. Our selections reveal the crucial importance of philanthropy both during the war and after the Allied victory in North Africa, when the American Friends Service Committee and HICEM managed to facilitate the freedom and emigration of some of the interned. Finally, the sources that follow testify to the resilience of the victims and prisoners of the Vichy, Nazi, and Italian fascist regimes. These individuals leaned on art, poetry, comradery, faith, radicalism, humor, and the written word to retain a grasp on their humanity.

In Tunisia, labor and detention camps were maintained by France, Germany, and Italy, depending on the timing of war. After the Allied landing in North Africa, Germany initiated a six-month occupation of Tunisia (November 1942–May 1943), leaning on the Italians to thwart the Allied advance in Tunisia and Egypt. During its rule of Tunisia, the SS imprisoned some five thousand Jewish men in roughly forty forced labor and detention camps on the front lines and in cities like Tunis, with many of the imprisoned laboring on infrastructural projects. A young Albert Memmi, writing from a labor camp outside Tunis, poured the grief of a man nearly broken by forced labor into his diary: “Sometimes,” he wrote, “we ask ourselves if living is worth the pain.”

Some North African Jews and Muslims were interned and perished in Nazi internment, labor, and death camps in Europe. Jews of North African origin living in Paris and its environs, for example, were sent to the Drancy internment camp on the outskirts of Paris and, from there, to concentration and death camps in Eastern Europe. Among them were two extraordinary Jewish athletes you will encounter in these pages: the Tunisian flyweight boxing champion Victor Perez, who was annihilated in Auschwitz, and the competitive swimmer of Algerian origin, Alfred Nakache, who survived internment and forced labor in Auschwitz only to make a surprise return to the competitive stage. Smaller numbers of Jews and some Muslims were also deported directly from North Africa or Europe to Nazi labor and death camps in Europe, where some perished.

North Africa served as a militarized zone throughout these years, with violence being experienced not only on the front lines but also by the civilian population and the landscape of North Africa. The fascist Italian and Vichy French authorities, like the German authorities, engaged in the plunder of food from territory under their control, which in the case of North Africa caused widespread starvation and malnutrition. Combined with an acute drought and a typhoid epidemic, the effects were disastrous. Al-ḥusin Al-Geddari recalls how desperate families in his village of Lamḥamid, in the Anti-Atlas Mountains, had to resort to retrieving the shrouds of the buried dead to reuse them for the next deceased in line. Al-Geddari and his neighbors understood that local famine was state engineered, part of a global chain reaction spawned by war and occupation.

In November 1942, Operation Torch marked the Anglo-American defeat of the Vichy powers in Morocco and Algeria, opening a new front from which the Allies could combat the Axis powers and heralding an end to Vichy rule in Morocco.24 The arrival of the Allies was celebrated by many North Africans, especially North African Jews. Gathering on the streets of Moroccan cities, they welcomed the arriving troops with songs, likening them to a bride approaching her betrothed.

Yet Operation Torch proved a complex and partial victory. To win the alliance of the French, the American leadership accepted that French rule would remain in place in post–Operation Torch Morocco and Algeria, as it would later in Tunisia. Under the command of the French high commissioner General Henri Giraud, this new-old leadership preserved the anti-Semitic legislation of the Vichy regime until it ended in 1944. What’s more, Giraud allowed many of the Vichy camps, including labor camps in the Sahara, to continue to operate—in cases, with the same wartime overseers in place. In these untenable circumstances, prisoners’ release was delayed for upward of a year. The arrival of Anglo-American troops had the simultaneous effect of heightening American power in North Africa, a show of military and commercial force that many locals viewed with suspicion or outright hostility. As several sources in this book note, American soldiers also brought a renewed threat of sexual violence against North African women, just as had the arrival of European soldiers previously. The Axis powers had been defeated, but neither occupation nor vulnerability had come to an end.

As in Europe and across the survivor diaspora, reckoning with the traumas, memories, and history of the Second World War was a slow and jagged process in North Africa.25 Arguably this process is unfolding still.26 This book stands as part of a delayed but surging global interest in the wartime and Holocaust testimonies of North African Muslims, Christians, and Jews. Yet it is also true that this reckoning began in North Africa even before the Second World War came to an end.27 We conclude this book with a selection of sources, memoirs, testimonies, songs, and prayers that reach beyond the conclusion of the Second World War, speaking to the haunting legacy of occupation and war in North Africa. Some reveal the logistical, legal, and economic challenges wrought by the dénouement of Vichy, Nazi, and fascist Italian control; others point to the tremendous religious and existential angst carried into the wartime era. Perhaps the most haunting of these sources airs the painfully private ordeal of a Tunisian Jewish survivor of Auschwitz struggling to reacclimate to liberation and his home of Tlemcen, where no one—including, it seems, the author himself—is able to grasp the depths of his wartime trauma.

It has been our goal in crafting this book to represent the Second World War as it was experienced in North Africa, on a human scale, giving voice to the diversity of those involved. As the first English-language sourcebook on this topic, it is, inevitably, but a partial effort. Yet this collection does air the perspectives of an astonishing array of actors: women, men, and children; the unknown and the notable; locals, refugees, the displaced and the interned; soldiers, officers, bureaucrats, volunteer fighters and the forcibly recruited, people of a wide variety of ethnic and religious backgrounds. At times their calls are lofty, redolent with spiritual lamentation and political outrage. At times they are humble, voicing yearning for medicine for their children, a cigarette, or a pair of shoes. All told, they shed light on how war, occupation, race laws, internment, and Vichy French, Italian fascist, and German Nazi rule were experienced day by day, across North Africa (and beyond), through warfare, internment and forced labor, racism and race laws, theft, the despoliation of landscape, and the engineering of hunger. These human experiences, combined, make up the history of wartime North Africa.

1. Aomar Boum and Sarah A. Stein, introduction to The Holocaust and North Africa, ed. Aomar Boum and Sarah A. Stein (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019), 1–16; Daniel J. Schroeter, “Between Metropole and French North Africa: Vichy’s Anti-Semitic Legislation and Colonialism’s Racial Hierarchies,” in The Holocaust and North Africa, ed. Aomar Boum and Sarah A. Stein (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019), 19–49; Michel Abitbol, The Jews of North Africa during the Second World War (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1989).

2. Jens Hoppe, “The Persecution of Jews in Libya Between 1938 and 1945: An Italian Affair?,” in The Holocaust and North Africa, ed. Aomar Boum and Sarah A. Stein (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019), 50–75; Rachel Simon, “It Could Have Happened There: The Jews of Libya during the Second World War,” Africana Journal 16 (1994): 391–422.

3. Ethan Katz, “Did the Paris Mosque Save Jews? A Mystery and Its Memory,” Jewish Quarterly Review 102, no. 2 (2012): 256–87; Mitchell Serels, “The Non-European Holocaust: The Fate of Tunisian Jewry,” in Del Fuego: Sephardim and the Holocaust, ed. Haham Gaon and M. Mitchell Serels (New York: Sepher-Hermon Press, 1995), 129–52.

4. Raffael Scheck, Hitler’s African Victims: The German Army Massacres of Black French Soldiers in 1940 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

5. Aomar Boum and Sarah A. Stein, eds, The Holocaust and North Africa (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019).

6. Reeva S. Simon, Michael Laskier, and Sara Reguer, The Jews of the Middle East and North Africa in Modern Times (New York: Columbia University Press 2003); Michael Laskier, North African Jewry in the Twentieth Century: The Jews of Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria (New York: New York University Press, 1994).

7. Jessica Marglin, Across Legal Lines: Jews and Muslims in Modern Morocco (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014); Emily B. Gottreich and Daniel Schroeter, eds., Jewish Culture and Society in North Africa (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011); Sarah Abrevaya Stein, Saharan Jews and the Fate of French Algeria (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010); Maurice Roumani, The Jews of Libya: Coexistence, Persecution and Resettlement (Brighton, UK: Sussex University Press, 2008); Paul Sebag, L’histoire des juifs de Tunisie des origins à nos jours (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1991); Harvey Goldberg, Jewish Life in Muslim Libya: Rivals and Relatives (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990).

8. Pierre Flamand, Diaspora en terre d’Islam: Les communautés israélites du sud du Maroc: Essai de description et d’analyse de la vie juive en milieu berbère (Casablanca: Imprimeries Réunies, 1959).

9. Joshua Cole, Lethal Provocation: The Constantine Murders and the Politics of French Algeria (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019).

10. Michel Ansky, Les juifs d’Algérie: Du décret Crémieux à la liberation (Paris: Éditions du Centre, 1950).

11. Jessica Marglin, “The Extraterritorial Century: Nationality in the Nineteenth-Century Mediterranean,” American Society for Legal History Annual Meeting, Houston, TX, November 9–11, 2018; Daniel Schroeter, “Vichy in Morocco: The Residency, Mohammed V, and His Indigenous Jewish Subjects,” in Colonialism and the Jews, ed. Ethan B. Katz, Lisa Moses Leff, and Maud S. Mandel, 215–50 (Bloomington: Indian University Press, 2017); Sarah Abrevaya Stein, Extraterritorial Dreams: European Citizenship, Sephardi Jews, and the Ottoman Twentieth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

12. Liliana Picciotto, “Un groupe de juifs libyens dans la Shoah 1942–1944,” in La bienvenue et l’adieu: Migrants juifs et musulmans au Maghreb (XVe–XXe siècle), ed. Frédéric Abécassis, Karima Dirèche, and Rita Aouad, 45–56 (Paris: Karthala, 2010); Michele Sarfatti, The Jews in Mussolini’s Italy: From Equality to Persecution, trans. John Tedeschi and Anne C. Tedeschi (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2006).

13. Daniel Lee, “The Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives in Tunisia and the Implementation of Vichy’s Anti-Jewish Legislation,” in The Holocaust and North Africa, ed. Aomar Boum and Sarah A. Stein (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019), 132–45.

14. Dan Michman and Haïm Saadoun, Les juifs d’Afrique du Nord face à l’Allemagne nazie (Paris: Perrin, 2018); Michael Laskier, “Between Vichy Antisemitism and German Harassment: The Jews of North Africa during the Early 1940s,” Modern Judaism 11, no. 3 (1991): 343–69.

15. Ruth Ginio, The French Army and Its African Soldiers: The Years of Decolonization (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017); Serge Bilé, Noirs dans les camps nazis (Monaco: Le Serpent à Plumes, 2005).

16. Ethan Katz, The Burdens of Brotherhood: Jews and Muslims from North Africa to France (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015); Aomar Boum, “Partners against Anti-Semitism: Muslims and Jews Respond to Nazism in French North African Colonies, 1936–1940,” Journal of North African Studies 19, no. 4 (2014): 554–70.

17. Susan Slyomovics, “‘Other Places of Confinement’: Bedeau Internment Camp for Algerian Jewish Soldiers,” in The Holocaust and North Africa, ed. Aomar Boum and Sarah A. Stein (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019), 95–112; Georges Bensousan, “Les juifs d’Orient face au nazisme et à la Shoah,” Revue d’Histoire de la Shoah 205 (October 2016): 7–23; Michel Abitbol, “Waiting for Vichy: Europeans and Jews in North Africa on the Eve of World War II,” Yad Vashem Studies 14 (1981): 139–66; Charles Robert Ageron, “Les populations du Maghreb face à la propagande allemande,” Revue d’Histoire de la Deuxième Guerre Mondiale 29, no. 114 (1979): 1–39.

18. Gerben Zaagsma, Jewish Volunteers, the International Brigades and the Spanish Civil War (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017); Adam Hochschild, Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016); Christopher Othen, Franco’s International Brigades: Adventurers, Fascists, and Christian Crusaders in the Spanish Civil War (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013).

19. Daniel Schroeter, “Philo-Sephardism, Anti-Semitism, and the Arab Nationalism: Muslims and Jews in the Spanish Protectorate of Morocco during the Third Reich,” in Nazism, the Holocaust and the Middle East, ed. Francis Nicosia and Bogaç Ergene (New York: Berghahn, 2018), 179–215; Isabelle Rohr, The Spanish Right and the Jews, 1898–1945: Antisemitism and Opportunism (Brighton, UK: Sussex Academic Press, 2017).

20. Robert Paxton, Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order (1940–1944) (New York: Norton, 1975).

21. Joseph Billig, Le Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives, 1941–1944, vol. 2 (Paris: Éditions du Centre, 1955).

22. Aomar Boum, “Eyewitness Djelfa: Daily Life in a Saharan Vichy Labor Camp,” in The Holocaust and North Africa, ed. Aomar Boum and Sarah A. Stein (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019), 149–67; Geoffrey Megargee, ed., The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945, vol. 3, Camps and Ghettos Under European Regimes Aligned with Nazi Germany (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2018); Robert Satloff, Among the Righteous: Lost Stories from the Holocaust’s Long Reach into Arab Lands (New York: Public Affairs, 2006); Jacob Oliel, Les camps de Vichy, Maghreb-Sahara, 1939–1945 (Montreal: Éditions du Lys, 2005).

23. Susan G. Miller, Years of Glory: Nelly Benatar and the Pursuit of Justice in Wartime North Africa (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2021); Yehuda Bauer, American Jewry and the Holocaust: The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, 1939–1945 (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1996).

24. Nicole Cohen-Addad, Aïssa Kadri, and Tramor Quemeneur, dirs., 8 novembre 1942: Résistance et débarquement allié en Afrique du Nord: Dynamiques historiques, politiques et socio-culturelles (Vulaines-sur-Seine, France: Éditions du Croquant, 2021).

25. Susan G. Miller, “Sephardim and Holocaust Historiography,” in The Holocaust and North Africa, ed. Aomar Boum and Sarah A. Stein (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019), 220–28; Hanna Yablonka, Les juifs d’Orient, Israël, et la Shoah (Paris: Calmann-Lévy, 2016); Yochai Oppenheimer, “The Holocaust: A Mizrahi Perspective,” Hebrew Studies 51, no. 1 (2010): 303–28; Aron Rodrigue, Sephardim and the Holocaust (WashingtonDC, DC: Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, US Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2005); Hayim Azses, ed., The Shoah in the Sephardic Communities: Dreams, Dilemmas, and Decisions of Sephardic Leaders (Jerusalem: Sephardic Educational Center in Jerusalem, 2005).

26. Mémorial de la Shoah, “Les juifs d’orient face au nazime et à la Shoah (1930–1945),” Revue d’Histoire de la Shoah 2, no. 205 (2016).

27. Lia Brozgal, “The Ethics and Aesthetics of Restraint. Judeo-Tunisian Narratives of Occupation,” in The Holocaust and North Africa: New Research, ed. Aomar Boum and Sarah Stein (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019), 168–84.