“You were speaking about us, weren’t you.”

So said a CEO who walked up to us after a presentation we gave at a leadership team conference years ago. He first expressed his thanks for our address and then leaned in, almost whispering the words quoted above. We soon learned he was alluding to a conflict we had described onstage that he believed had been taken from his own leadership team’s experience, a team we knew well.

It was not, but it could have been.

Why? Because the conflict in question afflicts almost all leadership teams (LTs), something this CEO had not realized. He had assumed the conflict was specific to his team.

This story highlights something about LTs we have observed after years of studying and working with them: the vast majority suffer from a common set of generic dysfunctionalities, but these are not always easy to distinguish from those that are team specific. As a result, LT issues are often misdiagnosed, and consequently the wrong remedies are applied.

This book will help you correctly diagnose issues affecting your LT and propose appropriate remedies to deal with them. These remedies are practices designed for, and successfully implemented by, actual LTs. Along the way, we address the questions CEOs ask us most often:

• How can I minimize power and politics on my LT?

• What do I do about silos?

• How do I get my team members to put the organization’s success ahead of their own?

• Who should sit on my team, and is it too big now?

In providing answers to these questions, we tackle two pressing LT issues. The first is why conflicts are so prevalent on LTs and what CEOs can do to manage them so they can spend their time doing something other than mediating disputes. The second is why it is difficult to create an environment where LT members take their role as organizational leaders seriously and are invested in decision making that addresses issues outside their immediate area of responsibility. As one newly named CEO once complained to us:

My whole career, I’ve been a team player. I don’t want to make decisions by myself. But getting [my team members] to pitch in on topics that don’t impact them directly is like pulling teeth. I ask a question and what do I get? Crickets.1 So I end up making a lot of decisions by myself but then they criticize me for it! I’m not complaining but, you know, it really is lonely at the top sometimes.

While this is not a self-help book intended to cure such loneliness, it will help you increase your LT’s alignment, a critical dimension of LT effectiveness.

You may already believe that improving your LT’s effectiveness and alignment is important. However, it is worth highlighting five reasons why all leaders and board members should be paying more attention to their LT:

1. Alignment: Critical but difficult to achieve. An organization’s misaligned LT inevitably leads to misalignment and dysfunctionality at the levels below, which makes LT misalignment more than a team issue. It is an organizational problem.

This is hardly news to CEOs, which is why so many are concerned with their executives’ alignment.2 Unfortunately, most CEOs’ efforts to achieve and maintain alignment are less successful than many would hope. In an article tellingly entitled “No One Knows Your Strategy—Not Even Your Top Leaders,”3 the authors report that only slightly more than 50 percent of LT members in the typical organization they surveyed agreed on their organization’s strategic priorities. A study by McKinsey & Company paints a similar picture: while executives agreed that being aligned on their purpose was critical, only 60 percent of them reported that they were.4

Our experience has been no different. Whenever we begin an LT engagement, we ask team members to name their organization’s top strategic priorities. After nearly two decades, we have come across few LTs with full agreement among its members on more than one or two. Nevertheless, many CEOs and team members believe they are very much aligned as they unknowingly pull in opposite directions.

2. More turbulence outside, more turbulence inside. The second reason organizations need to pay more attention to their LTs is the growing turbulence in most industries. While every decade sees commentators declaring that turbulence has increased, the argument that it has increased significantly in recent years is compelling.5 For example, on the economic front, one can point to international trade issues arising out of geopolitical tensions between old and new superpowers and to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had companies everywhere rethinking their supply chains, among other things.6 With increased turbulence in the external environment, internal alignment at the top becomes more difficult to achieve, provoking a ripple of conflicts at the levels below.7

3. The diversity imperative. In the social sphere, the underrepresentation of women and minorities in senior leadership positions has put pressure on organizations to diversify their top teams. This is a long-overdue priority that offers many benefits, including increased creativity.8 Yet we must recognize that diversity means aligning more perspectives, which may lead to more conflict. LTs already manage a significant amount of conflict. But since few can boast of doing it well, diversity poses a significant challenge. Working out how LTs can deliver the benefits of diversity while maintaining alignment is critical.

Working out how LTs can deliver the benefits of diversity while maintaining alignment is critical.

4. A trust deficit in an increasingly virtual world. When we started this project, COVID-19-related disruptions were spurring an increase in virtual contacts between LT members. We do not expect this to change in coming years given rapidly improving videoconferencing technologies and concerns over climate change. The result is fewer face-to-face LT member meetings, which in the past were always assumed necessary for building trust. This makes it imperative that executives understand what measures can be taken to build trust as in-person contact between LT members drops off.

5. A grossly underused value creation lever. Finally, as many CEOs admit, an effective LT is the main lever they possess to influence their organization and achieve their goals.9 Given how critical this lever is, developing your LT team’s effectiveness may be the most potent value creation mechanism at your disposal since it requires little financial investment and, unlike organization-wide improvement initiatives, does not necessitate buy-in from hundreds of people. Why would you choose to overlook it?

That almost 50 percent of CEOs admit that developing their LT is challenging should not come as a surprise.10 A lot of mystery surrounds how effective LTs really work. Why this is the case is worth considering because it explains why many LT practices viewed as best are rarely that.

First, few CEOs make a habit of seeking help when they wish to improve their team’s effectiveness because many perceive their LT issues as rooted exclusively in interpersonal conflicts rather than in dynamics common to all LTs.11 Accordingly, the practices they choose to meet these issues, whether good or bad, are rarely publicized. A second, and more important, reason for the shortage of true LT best practices is how few people have had in-depth exposure to a wide range of LTs.

Executives generally have a very small sample of high-performing LTs from which to derive good practices.

Consider the executives who sit on LTs. Rare are those we meet who have sat on more than a handful of LTs. Rarer still are those who say they have sat on effective LTs. Thus, executives generally have a very small sample of high-performing LTs from which to derive good practices.

The same is true for consultants. Many may work alongside LTs, but few get to observe LTs as they go about their everyday business. The reason is simple: LTs do not like to air their laundry, dirty or otherwise, in front of strangers. Even when consultants do get to watch an entire LT at work, it is usually when they are facilitating a session on a project they are entrusted with or they are at an offsite meeting where time is spent on “team-building” activities. In such artificial environments, LT members know it pays to be on their best behavior lest the consultant tell their CEO that they are “poor team players.”

The LT dynamics that consultants perceive are further distorted by savvy executives who try to co-opt them. As one executive once confided, “I always invest time helping our consultants and giving them my opinion on our team. In that way, they take my side when they talk to my CEO.”

Finally, we have LT scholars. Although many have delivered significant insights, they are the first to admit that obtaining permission to observe LTs is challenging, a well-known issue across social scientists studying such 12 This is understandably so, as CEOs see little benefit, and much risk, in letting scholars eavesdrop on strategic discussions, especially when their company is publicly traded.

That much LT advice rests on limited firsthand knowledge of LTs is something we want to remedy with this book.

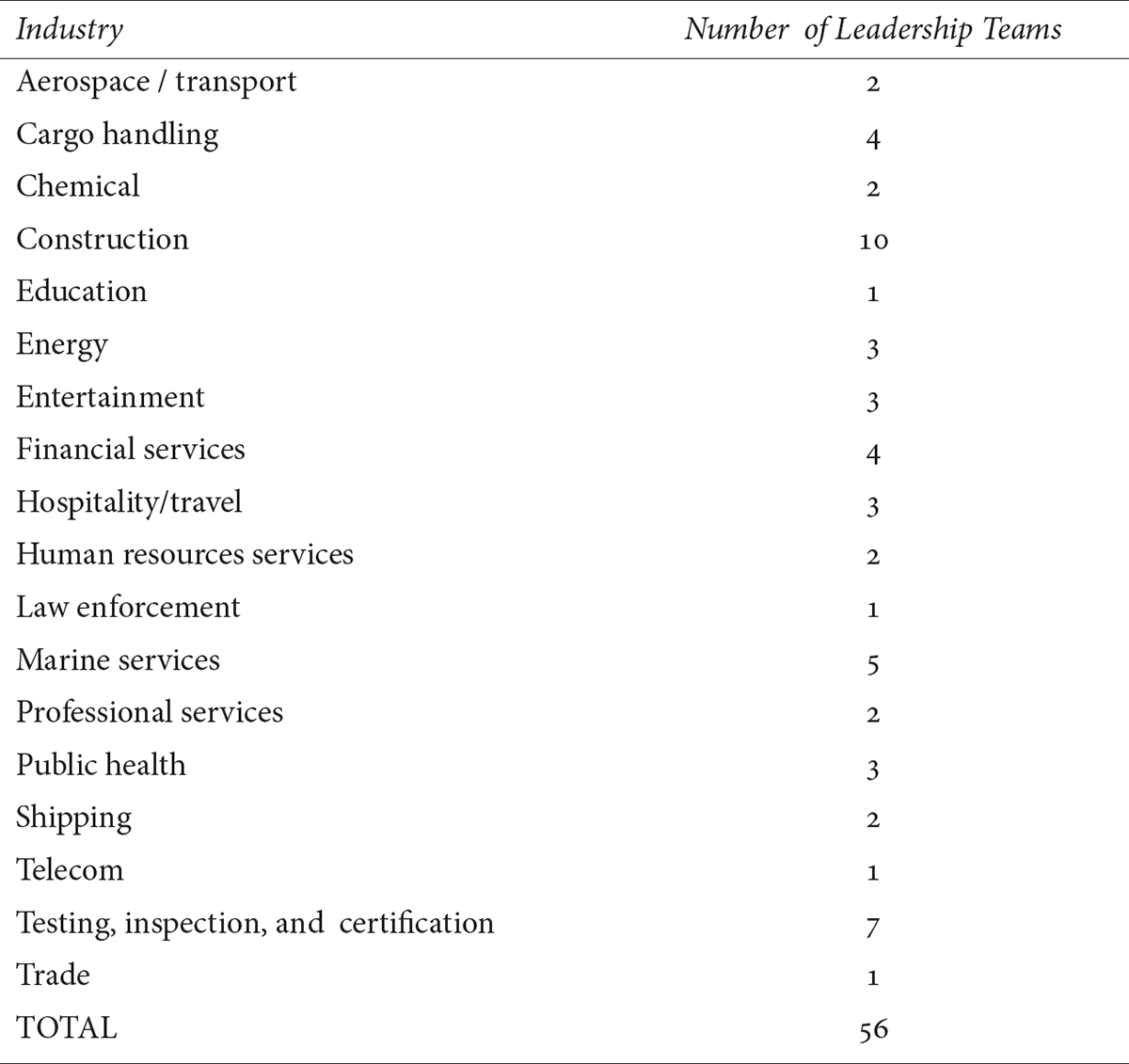

The insights and ideas you will find here are based on over eight hundred hours of direct observation of fifty-six LTs in eighteen different industries over two decades. We spent countless more hours with CEOs and individual members of these LTs assessing their team’s challenges and implementing solutions to address them.

Of the fifty-six teams, thirty-three were based in North America, eighteen in western or eastern Europe, and the remaining five in Asia-Pacific. Of the five in Asia-Pacific, four were based in Asia proper. However, it is important to note that these organizations were business units of American and European companies.

The types of engagements we performed for these LTs can be classified in the following manner:

• 34 percent were straight LT coaching engagements where a CEO wanted support to increase their team’s effectiveness.

• 28 percent were senior leadership offsites like those that thousands of organizations hold annually.

• 20 percent were strategic planning engagements.

• 9 percent were to assist the client organization in a corporate restructuring.

• 9 percent were to provide support in a postmerger integration context.

Our work is also informed by exchanges with the more than fifteen hundred CEOs and senior executives of some of the world’s top companies who attended our executive education classes in Europe and North America during which they shared their LT challenges.

Finally, our fieldwork is complemented by an in-depth study of the literature applying to LTs from a wide array of fields (e.g., management, sociology, politics, negotiations) as a means of testing and validating the insights gained through our contacts with LT leaders and members.

References to this literature are found throughout this book, and the details are in the Notes and References. This is to promote ease of reading but also to give precedence to the real-world experience of executives because of the gap between the way LTs are described in some of the literature and how they operate in the field. For example, some LT literature ignores the power and politics prevalent at the top and so promotes practices meant for an environment that hardly resembles the one in which executives work. Other writings promote practices emerging from nonexecutive team research despite it being widely acknowledged that such teams vary appreciably from LTs.13 Thus, the adage. “In theory, theory and practice are the same. In practice, they are not,” often applies to LTs.14

If we recommend a practice in this book, it is because we have seen it implemented by an actual LT. If we have not, we say so.

LT Leaders, Our Primary Audience

Because LT leaders are afforded less and less time to achieve results before being shown the door, they need to build and develop their LT quickly.15

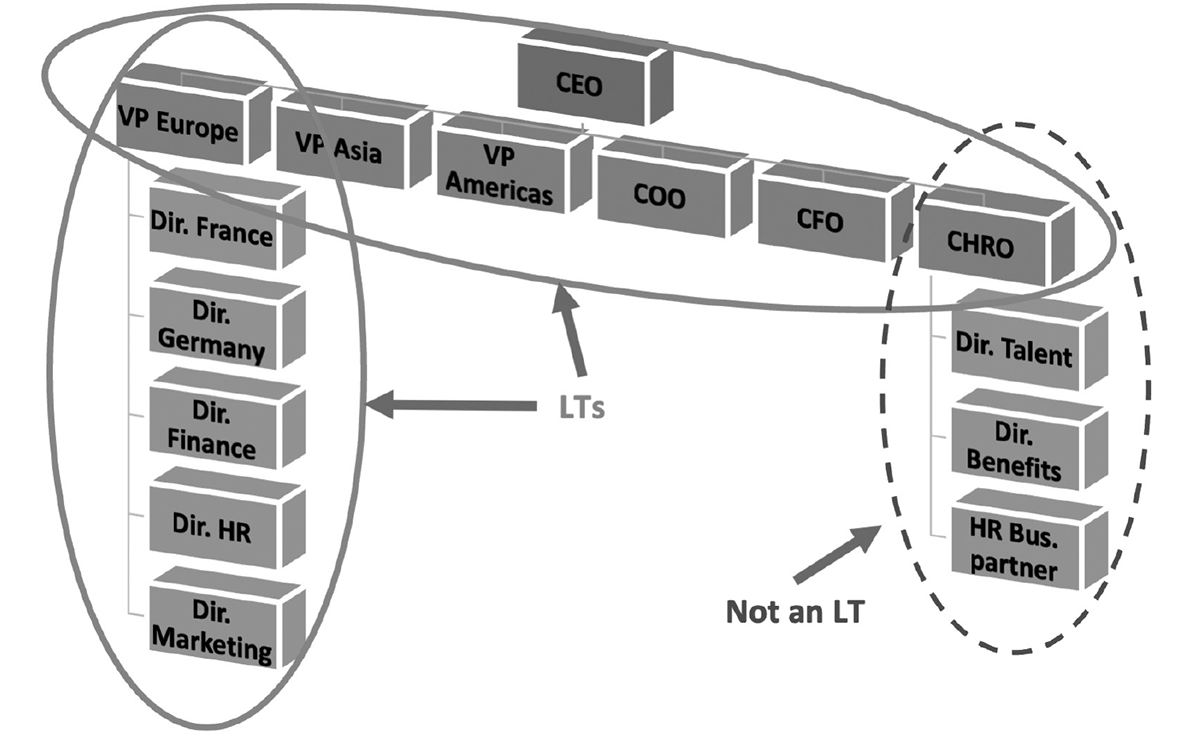

For simplicity, we label these leaders chief executive officers (CEOs), but they also include regional and business unit managers in large and medium-sized organizations. For example, the company depicted in Figure 0.1 has four LTs: the one under the CEO, as well as one under each of the three regional VPs: Europe, Asia, and America. (Note: we only represented two of these LTs in full).

We show the details of the European vice president’s team to illustrate how it qualifies as an LT, notably because it has a mix of executives with operational and functional responsibilities. In contrast, the chief human resource officer’s (CHRO) team is not an LT for the purposes of this book because it does not have such a mix.

Secondary Audiences: Executives and Board Members

After CEOs, we target two other audiences who have an interest in well-functioning LTs. First are the executives who sit on LTs, many of whom tell us their colleagues are the greatest obstacles to their success. While that may be true at times, a more common reason executives struggle once they reach the top is that they do not immediately grasp the implicit rules of the game. By making those rules explicit, we enable executives to better contribute to their organization’s success and to their own.

Next are board members. We add our voices to those who believe boards should play a more proactive role in supporting CEOs to assess their teams.16 Although board members we meet agree that an effective LT is critical, the majority admit they have never considered assessing their organization’s LT as a team. They may assess LT members individually, for example, by using 360-degree-feedback tools, but these are not designed to assess team dynamics. At best, they indicate if LT members get along, but that hardly qualifies as a team assessment because, as we shall see, there is no evidence linking LT effectiveness to LT members getting along. In fact, LT members who get along too well should raise a red flag.

Last But Not Least

We hope our book will also help consultants who advise LTs and are looking for a sound framework to diagnose LT dysfunctions and remedies to address them, just as we hope some of our insights may help LT scholars since many of their insights have helped us.

Last, at the risk of giving this book an “appropriate for everyone” label, it may also be of interest to those concerned with corporate governance issues. Given the important role that public and private organizations play in our economy, we hope that gaining a better understanding of how they work and are governed proves useful.

The two of us grew up on different sides of the Atlantic, and as we discovered, this has shaped the way we read business books:

• Frédéric prefers the classic, front-to-back approach.

• Jacques prefers jumping straight to the topics that most interest him and might skip the others.

To facilitate both approaches, chapters are divided into sections and subsections, each titled to identify the issues they address. Whichever approach you adopt, here is what you will find in this book:

In Part I, we single out three differences between LTs and nonexecutive teams that largely explain why commonly used practices to improve LT alignment and effectiveness are rarely successful.

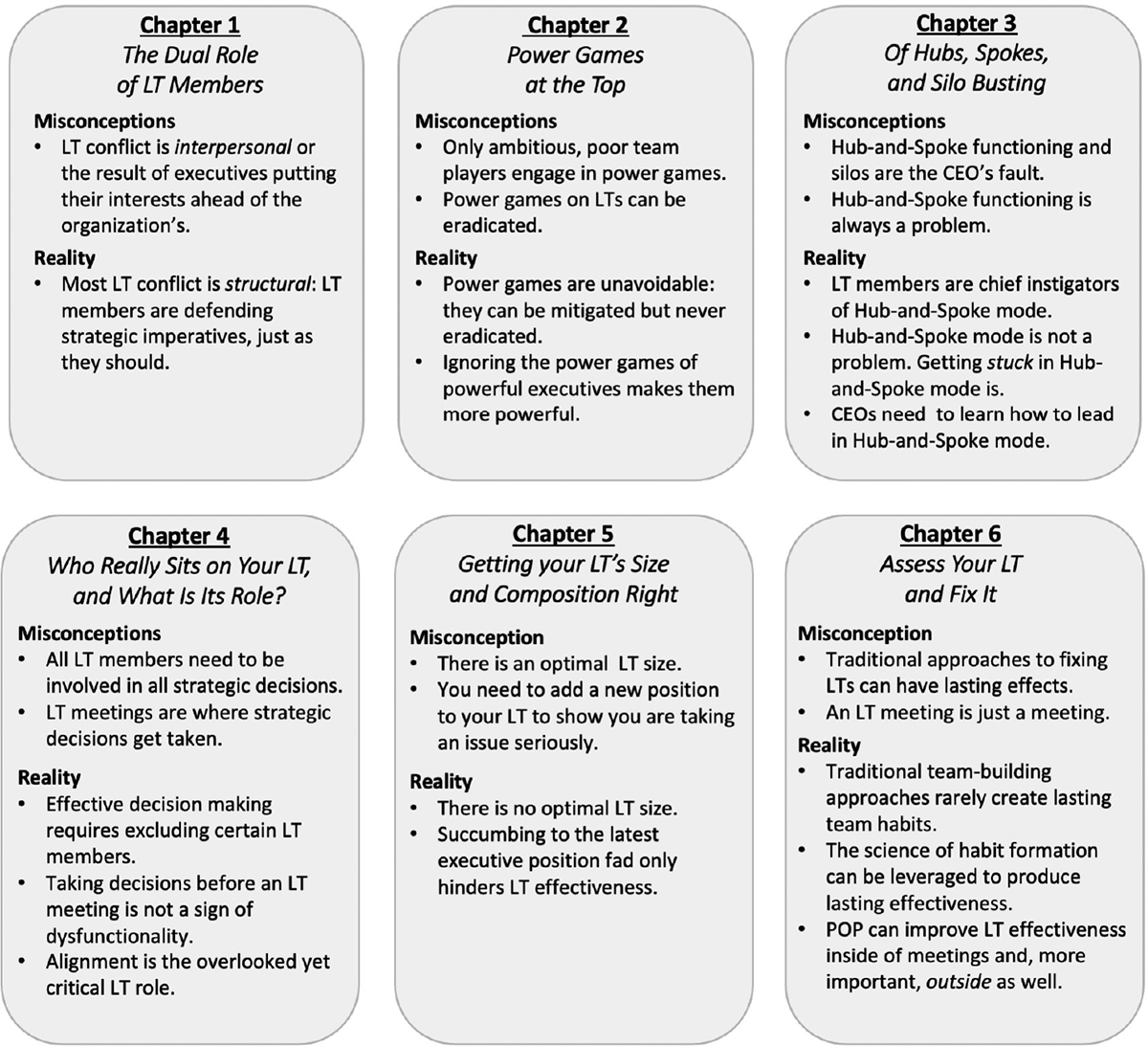

In Chapter 1, we address the dual role of LT members. An LT member wears two hats: the first as leader of their unit, by which we mean a business unit or function (e.g., human resources, information technology) and the second as leader of the organization. Much of the conflict and misalignment on LTs stems from the difficulty LT members have in reconciling their responsibilities under both hats.

Chapter 2 addresses the saliency of power games on LTs. Many observers denounce such games as if this were sufficient to make them disappear. Meanwhile, new LT members are bewildered to hear their CEO say there is no place for power and politics in their organization but then notice that those who succeed are colleagues who are most adept at power games and who enter their CEO’s inner circle. In this chapter, we explore why power games are inevitable and what effective CEOs we have met do to minimize their impact.

In Chapter 3 we address why many LTs get stuck in Hub-and-Spoke mode whereby CEOs interact one-on-one with LT members who live in silos, interacting very little with colleagues outside LT meetings.

At the end of each of these three chapters, you will find an “Actionable Insights” section that presents practices to meet the challenges raised in the chapter. You will also find “The Chapter in a Nutshell” section summarizing the chapter’s key concepts. Figure 0.2 highlights some of the misconceptions each of these chapters address.

Part II addresses how to improve specific aspects of your LT. We have taken into consideration that LTs vary according to myriad factors, such as size (their own and that of the organization they belong to), the nature of their organization (e.g., public, private, family owned), and the profile of its members. We have chosen to focus only on solutions that can be applied universally.

Chapter 4 seeks to dispel three misconceptions about an LT’s role in strategic decision making and address what may be the most critical role LTs are meant to play but rarely play well.

Chapter 5 focuses on the principles that will help you determine your LT’s optimal structure, including its size and membership, considering your organization’s strategy and its business model.

Chapter 6 addresses how to assess your LT by outlining the three dimensions you should be paying attention to. We then propose a tried-and-true approach to improve your LT’s alignment and effectiveness more rapidly than other often advocated approaches.

These three chapters in Part II also end with “Actionable Insights” and “The Chapter in a Nutshell” sections and Figure 0.2 highlights misconceptions addressed in chapters 4, 5 and 6.

This book offers many cases, and except where noted, all come from organizations we know firsthand. To protect the innocent (and the not-so-innocent), the names of protagonists have been modified unless the events recounted are in the public domain.

Now all that is left for us to do is to let you read on. We hope you find the answers you seek. If you have any questions that are not raised in this book, we encourage you to share them by writing to us at leadershipteamalignment@insead.edu.

We will respond to as many as we can and may well address those that occur repeatedly in our future work.

1. “Crickets” is a British idiom meaning “no reply or reaction at all” (https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/crickets).

2. Louis Hébert et al., Paroles de PDG: comment 75 grands patrons du Québec vivent leur métier (Montreal: Les Éditions Rogers Ltée, 2014).

3. Donald Sull, Charles Sull, and James Yoder, “No One Knows Your Strategy—Not Even Your Top Leaders,” MIT Sloan Management Review 59, no. 3 (2018).

4. Natasha Bergeron, Aaron de Smet, and Liesje Meijknecht, “Improve Your Leadership Team’s Effectiveness through Key Behaviors,” McKinsey Quarterly (2020), https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/the-organization-blog/improve-your-leadership-teams-effectiveness-through-key-behaviors.

5. José Luis Alvarez and Silviya Svejenova, The Changing C-Suite: Executive Power in Transformation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022).

6. Many academic and nonacademic sources allude to this question with a broad variety of competing views—for example, Henry Kissinger, World Order (New York: Penguin, 2014), https://books.google.fr/books?id=NR50AwAAQBAJ.

7. David N. Berg, “Senior Executive Teams: Not What You Think,” Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research 57, no. 2 (2005).

8. “Creativity has become a necessity for many organizations because it may help them thrive in uncertain environments: F. C. Godart, S. Seong, and D. J. Phillips, “The Sociology of Creativity: Elements, Structures, and Audiences,” Annual Review of Sociology 46 (2020): 489510. Diversity is one way to achieve creativity at the organizational level.”

9. Alice Cahill, Are You Getting the Best Out of Your Leadership Team? (Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership, March 31, 2020). Nearly all the senior executives in the study (97 percent) agreed that “increased effectiveness of my executive team will have a positive impact on organizational results.” EgonZehnder, The CEO: A Personal Reflection (Zurich: EgonZehnder May 11, 2018), 34: “As most executives know, a new CEO cannot and will not succeed without a strong team.”

10. EgonZehnder, The CEO. 34

11. As Sigal G. Barsade et al., “To Your Heart’s Content: A Model of Affective Diversity in Top Management Teams,” Administrative Science Quarterly 45, no. 4 (2000), 826, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.2307/2667020, write: “Also, as J. Richard Hackman, “Designing Work for Individuals and for Groups,” in Perspectives on Behavior in Organizations, ed. J. Richard Hackman, E. E. Lawler, and L. W. Porter (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1983), 257, pointed out, “Too often managers or consultants attempt to ‘fix’ a group that has performance problems by going to work directly on obvious difficulties that exist in members’ interpersonal processes. And, too often, these difficulties turn out not to be readily fixable because they are only symptoms of more basic flaws in the design of the group or in its organizational context.”

12. Richard Leblanc and Mark S. Schwartz, “The Black Box of Board Process: Gaining Access to a Difficult Subject,” Corporate Governance: An International Review 15, no. 5 (2007), 843, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467–8683.2007.00617.x.

13. For example, see Donald C. Hambrick, “Top Management Teams,” in Wiley Encyclopedia of Management.

14. This quote is often attributed to Albert Einstein, although it has also been attributed to many others, including New York Yankee baseball player Yogi Berra. According to the website “Quote Investigator,” there is no substantive reason to credit either of them, and the expression may have originated with a student writing in a Yale student publication in the 1880s (https://quoteinvestigator.com/2018/04/14/theory/ accessed September 19, 2022). However, this is not something we have verified.

15. Peter Cappelli, Monika Hamori, and Rocio Bonet, “Who’s Got Those Top Jobs?,” Harvard Business Review 92, no. 3 (2014).

16. Including Yazmina Araujo-Cabrera, Miguel A. Suarez-Acosta, and Teresa Aguiar-Quintana, “Exploring the Influence of CEO Extraversion and Openness to Experience on Firm Performance: The Mediating Role of Top Management Team Behavioral Integration,” Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies 24, no. 2 (2017), 210, https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051816655991, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1548051816655991, and Scott Keller and Mary Meaney, “Attracting and retaining the right talent,” McKinsey Global Institute study (2017). who write that 90 percent of investors think the quality of the management team is the most important nonfinancial factor when evaluating an IPO.