St. Valentine’s Day, 1944. Lilly Rubin, a Jewish woman living in Budapest, sends a picture of her four-year old daughter to her sister Magda, who is hiding somewhere in France. A month later, the German army will invade Hungary and Adolf Eichmann will set up his headquarters in the capital; the roundup and deportation of provincial Jews will be accomplished with amazing efficiency, eliminating all of Lilly’s extended family. But she doesn’t know that now. Does she know about the Warsaw ghetto, about Treblinka, about the deportations from France? Does the name Auschwitz mean anything to her? I dream about this as I finger the photograph, then flip it to read the inscription on the back, written in her spidery handwriting: “To my sweet good Magduska, with much love and many kisses from little Zsuzsika.” My aunt Magda, Mother’s younger sister, had emigrated with her husband and daughter to France in the 1930s. Evidently, this picture was enclosed in a letter: to Magduska from Zsuzsika, the diminutives showing intimacy and familiarity, though in fact she had never seen me. Beneath the message, the date: Budapest, 14-2-1944.

I have fished the photo out of a drawer where it lay along with others, helter-skelter, still in the original plastic bags and manila envelopes where Mother had kept them. Some of the black-and-white photos are torn, stained, of people whose names I no longer know, if I ever did. Some were clearly torn from an album, with bits of black paper stuck to the back. She had carried them around since August 1949, when we escaped from Hungary. I can imagine her on that summer day: she has to pack a suitcase, not too big, not too heavy—we are about to set out on foot across the border. What do you take with you on such an occasion? A few pieces of jewelry (there was not much anyway), warm clothing (it’s August, but one never knows), and of course photos. But the album is too heavy, the pictures will have to go solo. “Just a few, when she was a baby, then a bit older, then from last year when we had the photographer come to the house—she wore the new dress I had had made for her.” She hurriedly tears out the photos and stuffs them into the suitcase.

They’re mixed in with colored snapshots I had sent her over the years: me with my two boys, me and my husband before our divorce, and earlier, before our marriage. Among the black-and-white photos is one of me at my college graduation, standing next to my mother, smiling, looking lost. Like a fatherless child? My father had died of a heart attack the previous summer, just before the start of senior year. But looking lost, feeling lost, had been familiar to me since childhood.

I had seen most of the old pictures while Mother was still alive, on the rare occasions when she consented to talk about our life in Budapest, the life we had left when I was ten years old. Usually, she avoided the subject: “That’s behind us, forget about that,” she would say firmly—but she said it in Hungarian, a fact that undercut the meaning of her words. The past is another country, historians have said. Can you forget a country whose language you still speak? My mother and I always spoke Hungarian when we were together.

I visited her in Miami Beach once or twice a year, and she would bring out the photos if I begged her, naming the people who were unfamiliar to me: provincial uncles and their families who had perished in the Holocaust; two of her cousins who survived, beautiful young women who had given her photos inscribed in the back with Love to Lilly. We would also look at pictures of me as a baby, a toddler, a schoolgirl. (“That was when I was a boy,” I would joke at the photo of me at six months, lying on my stomach, almost completely bald.) “How cute you were, see, so blond!” she would say, fingering a picture of me at age two. Or: “I always liked that blue dress on you—we had it made in 1948, the year Granny left.” And then, at last, she would start reminiscing: “Do you remember our Sunday hikes in Buda, our trips to the bookstore on Andrássy Avenue? You loved those books about Zsuzsika, the little girl who had your name—when you finished one, we’d go and buy the next one in the series. And the ice skating rink in City Park, where I would watch you skate.” Yes, I remembered. I always shivered from the cold at the skating rink and didn’t enjoy it, but she wanted me to learn how to skate and take ballet lessons and play the piano, all the things she had missed out on in her childhood. I was her only child (my sister was born much later), while she had grown up with three brothers and a sister in a family that had become fatherless when she was still a teenager. She had had no time for luxuries, and she wanted me to have them.

The photo she sent to her sister in 1944 was posed in a photographer’s studio. Mother had made a special appointment with the fancy photographer, and the session probably lasted for several hours. In the end, she chose two pictures. In this one, my hair is loose around my shoulders, with a big silk bow on top; I wear a pretty cotton dress and a gold chain around my neck; a straw shopping basket hangs from my left arm, while the right hand holds the leash of a toy poodle on wheels. I am a young lady going out to do her daily shopping with her dog. Facing the camera, I smile and my eyes sparkle. Imprinted on the bottom right-hand corner is the name of the studio: Mosoly Albuma, Album of Smiles, with its address and phone number. At least some people were still smiling in Budapest in February 1944.

The other photo from that studio is even more absurd. With my hair in braids and two small bows instead of the big silk one, an apron over my pretty dress, I stand in front of a toy stove, my right hand resting on the lid of a pot sitting on the stove: busy housewife. Once again I’m smiling at the camera, this time even more broadly—I must have been aware of the silliness of the pose.

Mother loved beautiful things: the silk bows, the gold necklace. Maybe she didn’t want to know what was happening. Maybe she thought we were safe. Hungary was Germany’s ally, though by then a reluctant one. The Germans invaded in March 1944 to make sure it didn’t bolt, and to take care, at last, of the Hungarian Jews.

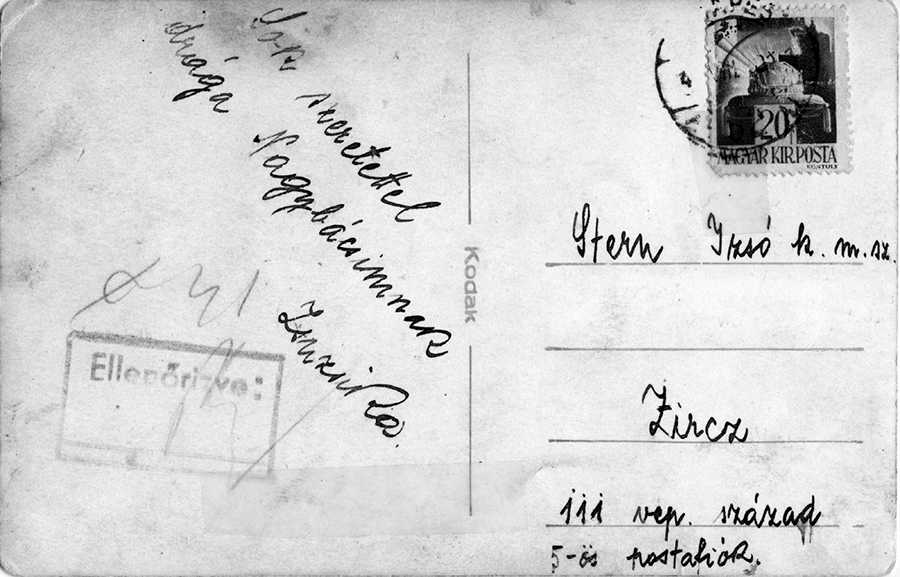

About forced labor, at least, she knew: the photo with the toy stove is addressed as a postcard to her brother Izsó Stern, at a postbox number and the number of a regiment. The Hungarian army had begun conscripting Jewish men into forced-labor service in 1940, and my uncles Laci and Izsó were among them. I have read about the forced-labor units, seen a few films too. At first, the men were relatively well treated, if one can say that about civilians forced to work long hours clearing woods and carrying rocks, undernourished and ill-clothed. Later, it got much worse. In the winter of 1943, the Hungarian army was routed by the advancing Russians in Ukraine, at the river Don; Jewish conscripts, now seriously deprived of clothes and shoes and food, were set to clearing minefields ahead of the regular troops. If they were not blown up, they starved or froze to death by the thousands, or died of exhaustion, or were beaten or shot for sport.

My father too spent time in forced labor, but Mother always said he had been released after a few weeks, thanks to her entreaties to the authorities: he was a rabbi, he worked for the Orthodox Community Bureau, he had a young child to support, she had pleaded. Somewhat to my amusement, my aunt Rózsi, my father’s younger sister, told the same story, but according to her it was she who had pleaded and obtained his release! The main thing was, he had returned safe and sound not long after being taken. But a document I discovered only recently, which my father filled out in 1945, after the war was over, states that he had been in forced labor from December 1942 to February 1944—more than a few weeks. The document also states—in his careful handwriting, which I recognize instantly—that he had been in Russia, the worst possible place to be in forced labor. If the dates are correct (I say if, because he may have had reasons to prolong his captivity on paper—documents are not always one hundred percent trustworthy), he had returned from captivity on February 9, 1944, five days before my mother sent the photo of me to her sister. But she must have taken me to the photographer before that, which strikes me as an odd thing to do at the time. I suppose life went on, even if your husband was in a forced-labor unit in Russia (if indeed he was there).

My uncle Izsó died in forced labor—that we were sure of, although we never knew exactly where, or when. His brother Laci, who was in a different unit, had lost track of him early on. For a long time after he returned, Laci kept repeating, whenever Izsó’s name was mentioned: “He was too gentle, he didn’t know how to scramble for food, allowed others to take advantage of him—if only I had been there to help!” Laci always landed on his two feet, or so he thought. Personally, I think his survival owed more to luck than to any cleverness on his part. But these things are complicated. Maybe there was cleverness as well.

Now here is this postcard featuring me as a four-year old housewife, addressed to Izsó, in a regiment in a place called Zircz. My mother’s message to him reads: With much love to my dear uncle, signed with my name, Zsuzsika. No date. There is a stamp with a postmark, indicating it was actually sent, but the postmark is illegible, even with a magnifying glass. Assuming that she sent this photo around the same time as the one to her sister, the card must have gone out in mid-February 1944. Was he dead by then? I hope not. I hope he received the card and smiled at his little niece’s absurd pose. He was very fond of me, everybody said. I hope the photo made him smile.

But he did die, if not then, later. How did the picture get back to my mother? Perhaps it was returned, Addressee deceased? But there is no return address on the card. Or maybe it came back with a package of my uncle’s effects after his death? No, that would have been too civilized—and besides, there was never any official notification of his death. Maybe, when he saw that he was dying, he gave the photo to someone along with other papers and asked him to return it to the family if he survived. I imagine the scene: 1945, summer or early autumn, my grandmother is still waiting for her son. A man knocks on the door, stands in the doorway, looking uncomfortable, shifting from foot to foot: “I brought you this, Izsó asked me to.” No, that’s melodrama. I don’t know how the photo got back to us. Maybe he was given a leave from his unit in 1944 and brought it home with him, before he returned to die.

I look for more signs. The card is addressed to Stern Izsó, Hungarian style, last name first. After his name, the letters k.m.sz. In Hungarian, forced labor is called, euphemistically, labor service, munkaszolgálat; m.sz. is obviously an abbreviation for that, but what does k. stand for? This is the time to consult my bible on these matters, Randolph Braham’s big book on the Holocaust in Hungary. Braham gives two words beginning with K that went with munkaszolgálat: közérdekű, “public,” and különleges, “special.” Public labor service in the army, special labor service in Ukraine. It was special all right, unarmed, with no uniform, checking out minefields.

Where is Zircz? Sounds foreign, not Hungarian. Ukraine, the eastern front? I need a detailed map, which today is easy to find. Zircz (or Zirc, that’s what the map says) is the site of an ancient Cistercian abbey in northwestern Hungary near the Austrian border, not far from the city of Veszprém. Veszprém has been renowned as a center of learning since the days of Hungary’s first Catholic king, St. Stephen, who reigned in the eleventh century. Zircz is not in Ukraine but in authentic, historic Hungary, Magyarország—it was just one of those ironies to put a forced-labor camp in such a town, I tell myself. But then, Dachau is proud of its medieval churches, and Buchenwald was a stone’s throw from Weimar, where Goethe had lived and worked. Culture and barbarism, close cousins.

At least it wasn’t the eastern front. When my mother sent him that picture of me in front of the toy stove, Izsó–if he was still alive, and still in Zircz—was not checking out minefields, merely suffering from cold, hunger, backbreaking labor, the brutality of guards.

I fish out another photo, a small portrait of Izsó. He was a gentle man, with an oval face, brown eyes, wearing small, black, owlish glasses that look oddly fashionable today. His brown hair, smoothly combed, sits high up on his forehead; he is starting to get bald. He wears a dark gray suit, white shirt with soft collar, and wide striped tie; he is smiling slightly, with closed lips. A gentle man.

On the back of this photo, there is some very faint writing for which I need the magnifying glass. Stern Izsó, then his address in Budapest (which was also our address and my grandmother’s; we all lived in one large apartment) and a date and place: 1904 Nagymihály, evidently his year of birth and birthplace, then a more precise date, March 22, no doubt his birthday. Beneath that, his mother’s maiden name, Lebovits Teréz, then an official stamp with a notation in black ink and an illegible signature. The notation consists of a number, like an ID number, below which is a word that could be láttam, “I’ve seen him,” followed by a date: 1942, 12/30, and the signature. On December 30, 1942, an official person saw him, or gave him permission to leave, or to return. He was thirty-eight years old. The official stamped the back of his photo, and it too eventually found its way back to my grandmother and from her to my mother.

On page 338 of Braham’s book, I find the following information: in November 1942, the Ministry of Defense required all Jewish men aged 18 to 48 to register. “Each affected Jew had to bring along two snapshots, one of which, after it was stamped by both the recruitment center and the local bureau for vital statistics, was to serve as a ‘registration certificate.’” What I hold in my hand now is Izsó’s registration certificate, stamped and dated and bearing an official signature. Braham reproduces a similar photo, front and back, and I see that it carries the same vital statistics as Izsó’s: date and place of birth, permanent address, mother’s maiden name. It too has a stamp and a signature; its date is December 22, 1942, eight days before Izsó’s. Evidently, people were following the ministry’s orders. The unidentified man in the book (it was Braham himself) was born in 1922; he was much younger than my uncle. But Izsó wasn’t old. Thirty-eight is not old, when you lead a normal life.

Hungary has many place names beginning with Nagy: Nagyyaranypuszta, “great golden plain”; Nagyerdő, “great forest”; Nagylengyel, “great Pole”; Nagyszentjános, “great Saint John.” Nagymihály, Izsó’s birthplace, is “great Michael,” named after the archangel. In 1904, it was a busy industrial town in northeastern Hungary near the Carpathian mountains, part of the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy, aka the Habsburg Empire. World War I put an end to the monarchy and rearranged the map of Central Europe, distributing many border regions to other countries. Today, Nagymihály is in far eastern Slovakia and is called Michalovce, the county seat of its region. In 1910, 32 percent of the population was Jewish, just slightly less than the Catholics (39 percent). As far as I can tell, there are no Jews living there today.

The Stern family all came from that part of the world: Izsó’s parents, my grandparents, were married and lived for a while in Ungvár, today Uzhgorod in Ukraine, less than twenty miles east of Michalovce. In 1944, Ungvár had an even larger Jewish population than Nagymihály; many trainloads of Jews were sent to their death from Ungvár.

Izsó was my grandparents’ first child, born before they moved to Budapest, but like his siblings, he was a child of the capital, at home with its pleasures. I rummage for more pictures of him. Here are two small snapshots, clearly from before 1944. In one, Izsó stands with bare chest among a group of smiling men and women, all wearing bathing suits. Maybe it’s a Sunday morning at the swimming pool on Margaret Island, or at the Gellért baths. Izsó leans forward, his elbows resting on the back of a wicker armchair in which a young man is reclining; Izsó’s shoulder touches that of a blond woman who is sitting on the arm of the same chair. At the bottom of the picture, two little girls lean against the legs of the man and woman behind them, probably their parents. I have no idea who these people are; only Izsó’s face is familiar. (Odd, that I should recognize him instantly on the photo when I have no memory at all of the living man.) He is wearing his owlish black glasses. His hair is slightly tousled; his expression, though serious, is relaxed. He never married, but he evidently had good friends. He looks happy.

In the second picture, he wears his dark gray suit, with a white shirt and tie as in the registration photo. He sits on a park bench with a young couple dressed in summer white. The woman’s dress has a polka dot pattern, and she wears a fashionable straw hat with flowers and a ribbon; the hat is at an angle, low over one eye, giving her a coquettish look. She is smiling. The man’s hat is a light gray fedora, almost incongruous with his white suit. They sit very close to each other, and she wears a diamond ring on her left hand. Maybe they have recently gotten engaged. Despite their well-dressed appearance, there is something provincial about the way they look. Izsó is bareheaded, sitting at a slight distance from them. They may be provincial cousins from the large Stern family, on a visit to the capital—the three of them have been walking around City Park and have sat down for a rest. Or maybe the scene is not in Budapest, and it’s Izsó who has gone to visit them in their hometown. Wherever it is, it’s an occasion worthy of a photo, of celebration on a sunny summer day.

Provincial Jews from Hungary were almost all deported, close to half a million. Very few came back. Like Izsó, this couple will soon be dead, but they don’t know it. I feel offended by the obviousness of the tragic irony, the scalding but too-easy sense of time’s irreversibility these images produce. The people are long gone, while I am here, and I know what happened to them. But please, no philosophizing. Look at the way she leans against her lover’s arm, the way she wears her hat, at an angle, like Marlene Dietrich. The way the shadows play over her neck and face, over her smile. Just look.

The last picture I find of Izsó is a postcard-size photograph of a group of men, like a class picture: one row sitting, three rows standing, tallest in back. Behind them is a large open door, to a hangar or barrack. The photo has a long crack down the middle, mended with transparent tape on the back. Someone had torn it in half, then changed their mind; or maybe it was folded to fit in a pocket and got torn that way. The men are dressed in winter clothes, jackets and sweaters and overcoats. They wear no uniforms but look regimented. Most of them appear to be wearing a tricolor armband on their left arm (some of their arms are hidden)—no doubt the colors of the Hungarian flag: red, white, and green. Most are bareheaded; a few wear wool work caps. One man, chubby, wears an army cap—he sits to one side and wears a white cook’s apron over his wool jacket, a dishcloth slung over his shoulder. My uncle Izsó stands in the back row at the extreme left, bareheaded, in a dark overcoat, with a light-colored scarf around his neck. He is unsmiling, looking straight at the camera. They are all unsmiling, except the cook and one other man squatting in the front row. Why is that man smiling? He is one of the conscripts, wearing an armband. It must be the camera—some people can’t help smiling whenever a camera appears. But it’s not a happy smile; he is in half profile, glancing sideways at the camera.

Nothing is written on the back of the card, nor does any label or marking appear on the photo itself. Yet there is no mistaking it, this is a group of Jewish forced laborers: their pose, their look, their armbands all indicate what they are. I count twenty-nine of them, plus the cook; since he has no armband, he may belong to the regular army.

The men all look in relatively good health; the picture must have been taken in the early days, maybe right after Izsó registered in December 1942. Or maybe even earlier: many Jews were called up in ’40 or ’41, allowed to return home after a few months, then called up again. But why the class picture, and how did it reach my mother? Bizarre idea, a souvenir photo of a forced-labor camp. Was this in Zircz, or did Zircz come only later, when no more photos were taken?

Were there similar pictures, now lost, of the surviving brother Laci? Did he too receive a photo of me in his labor camp, busy at my stove or holding my toy dog by the leash? Was she also planning to send a photo to my father, not knowing he was about to arrive home? I don’t know, and there is no one around anymore to ask. My father died decades before my mother, and my aunt Magda and uncle Laci are gone too. While they were alive, we never talked about these things, and it appears I never turned the pictures over to see what was written on the back. The only people who mourned Izsó after the war were my grandmother and his siblings, who needed no photos to remember him.

I put the pictures back in the drawer without trying to sort them. Someday I’ll do it, get a nice album, organize them neatly, write notes about them for my children. Meanwhile, I ask myself: was she thoughtless and frivolous, taking me to the photographer like that, in February 1944? Of course she could not know what would happen a few weeks later: all her provincial cousins and uncles and aunts rounded up and murdered, we ourselves in hiding, hunted. But still, how could she continue her bourgeois rituals—the appointment with the photographer, the satin bows and silly poses—so late into the war? Unless it was that very perseverance that showed courage and insight: she would continue to affirm her life, our life, even in the face of destruction.